Upper Extremity Trauma

DAVID L. GILLESPIE and MARLENE O’BRIEN

Presentation

A 31-year-old male presents as a level 2 trauma alert for multiple gunshot wounds to the extremities. Upon arrival in the trauma bay, he is agitated and writhing in pain, although protecting his airway with an oxygen saturation of 98%. He is hemodynamically stable with HR 85, RR 24, and BP 125/98 mm Hg. On careful examination, he has lacerations over his right shoulder, two penetrating injuries over his bilateral buttocks, and a through-and-through penetrating injury of his left forearm. He has 2+ bilateral radial pulses and no associated pulsatile bleeding.

Left Upper Extremity X-Ray

Two paper clips overlie the proximal to mid forearm. Tiny metallic opacities are noted in this region amidst marked soft tissue swelling and some subcutaneous emphysema. No acute fracture is seen (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1 Left upper extremity x-ray demonstrating tiny metallic opacities and soft tissue swelling by an area of penetrating trauma (paper clips).

Approach

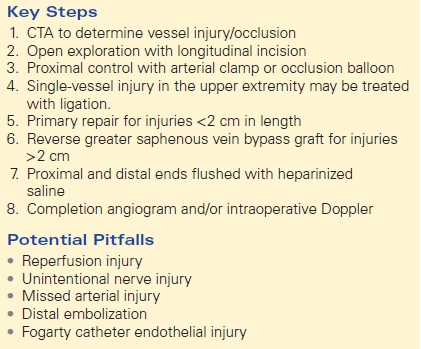

As with any acute trauma, the treatment algorithm starts with Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS): airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and exposure. The patient has palpable bilateral radial pulses, but has a penetrating through-and-through injury of his left forearm that raises concern for potential vascular injury. Only a minority of patients actually present with hard signs of traumatic vascular injury, including observed pulsatile bleeding, palpable thrill, audible bruit on auscultation, absent distal pulse, or a visible expanding hematoma (Table 1). A pulse deficit may not initially be present due to extensive collaterals in the arm; therefore, soft signs of traumatic vascular injury warrant further diagnostic workup: significant hemorrhage by history, neurologic abnormality, diminished pulse compared with contralateral extremity and proximity of bony injury, or penetrating wound (Table 1). A through-and-through penetrating injury of the left forearm, despite a palpable radial pulse, necessitates further investigation.

TABLE 1. Signs of Traumatic Vascular Injury

Case Continued

The patient’s left upper extremity is tender to palpation without crepitus. Sensory and motor function of both upper extremities is intact, although the left hand is markedly cooler than the right. Because he is hemodynamically stable and has multiple penetrating injuries, the decision is made to send him to the CT scanner for further imaging, including CT angiography of his left upper extremity.

Workup and Diagnosis

The patient has no hard signs of vascular trauma and is hemodynamically stable. At this time, the diagnostic test of choice is CT angiography. The main indications for CTA of upper extremity arterial injuries are as follows: (1) exclusion of vascular injury in the absence of clinical hard signs and (2) determination of injury location, nature, and extent of vascular injury when not clearly evident on physical examination. CTA has acceptable sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing vascular injury and has increasingly replaced both Doppler ultrasound and conventional angiography in the diagnosis of upper extremity vascular injury, except when a comminuted fracture may decrease its sensitivity.

Left Upper Extremity CT Angiogram

Abrupt cut off of the radial artery suspicious for arterial injury. No active extravasation. Irregularity of the ulnar artery. There is an associated large hematoma. No active extravasation. This may represent an arm compartment syndrome due to hematoma (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2 A: Left upper extremity CT angiogram demonstrating a patent radial artery proximally. B: Occluded radial artery with multiple surrounding flecks of air.

Recommendations

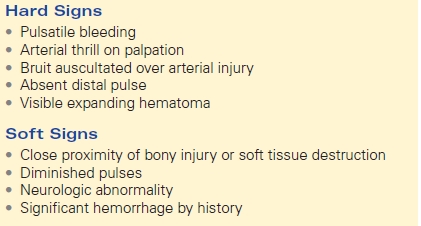

The patient should be taken to the operating room for a left upper extremity exploration and potential vascular repair. In cases of nonocclusive vascular injury, such as pseudoaneurysms or intimal flaps that do not threaten limb viability, conservative therapy with the initiation of antiplatelet therapy and repeat delayed imaging may be acceptable. In this case, however, the injury appears occlusive despite a reassuring physical exam. In situations where bony injury coexists with vascular trauma, vascular repair is usually undertaken prior to orthopedic repair because ischemic time is critical to overall outcome. Exceptions to this are in cases of unstable fractures, where external fixation is required immediately to stabilize the limb to prevent further injury to surrounding structures. Fortunately, this patient does not have coexisting fractures in the left upper extremity and his forearm exploration and repair can be initiated without delay.

Surgical Approach

Preoperative antibiotics with strong gram-positive coverage should be instituted before making a skin incision, and, in cases with known bony injuries, coverage for gram-negative organisms should be used as well. The entire extremity should be prepared and draped to make multiple options for revascularization readily available. In addition, an uninjured extremity should be included in the operative field in the event that autogenous vein grafting is warranted.

In most cases, extremity incisions are placed longitudinally, directly over the injured vessel, and extended proximally or distally as necessary. The first goal is proximal control of the injury to abate hemorrhage. When proximal control is challenging, the option of endoluminal balloon occlusion with fluoroscopic guidance from a remote site should be considered.

Once the injury has been identified, there are several options for arterial repair, including patch angioplasty, end-to-end anastomosis, interposition graft, or autogenous vein bypass graft. In cases where soft tissue damage is extensive and the segment of injured vessel is greater than 2 cm, bypass grafting is indicated. In general, autogenous vein is preferred to Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), except in cases where autogenous vein is inadequate or unavailable, when the patient is unstable and quick repair of the artery is critical, or when a large size discrepancy between the vein graft and native artery exists. In both blunt and penetrating trauma, the degree of intimal injury and/or occlusion can extend beyond the area of obvious injury, so care should be taken to pass a Fogarty catheter proximal and distal to the arterial injury to remove intraluminal thrombus. Both the proximal and distal ends should be flushed with heparinized saline solution.

Single-vessel injury in the forearm may not need to be repaired, but sometimes can be ligated or embolized because of collateralization provided by the superficial palmar arches. Incomplete arches, however, do exist in 3.6% to 21.5 % of patients. When both radial and ulnar arteries are injured, repair of the ulnar should be undertaken preferentially, because it is the dominant blood supply to the hand (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Upper Extremity Vascular Repair