18

Uncommon Tumors of the Lung

Tumors of Bronchi

Squamous Papillomas and Invasive Papillomatosis

In the airways, papillomas are usually exophytic; inverted papillomas are rare. Solitary papillomas occur most often in the bronchi of elderly smokers, whereas multiple papillomas (papillomatosis) tend to occur in children (juvenile papillomatosis). Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis is usually confined to the larynx, but in 2% of cases a spread to the lower tracheobronchial tree occurs.1–5 Frequent procedures to remove recurrent lesions may be necessary to maintain airway patency, usually laser therapy.6 Respiratory papillomas are caused by human papilloma virus (HPV) types 6, 11, and 18.7–10

Squamous papillomas are papillary tumors consisting of a delicate fibrovascular core covered with bland nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium, which may appear “transitional.” Viral cytopathic effect, for example, koilocytosis may be observed, as well as varying degrees of dysplasia and carcinoma in situ.11 Squamous cell carcinoma spontaneously develops in 2 to 3% of cases. Its frequency is increased by radiation therapy and perhaps with HPV type 11.9–18

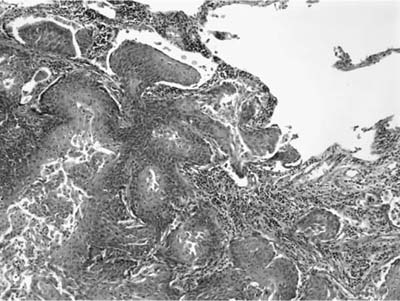

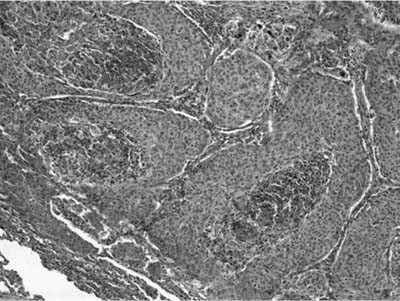

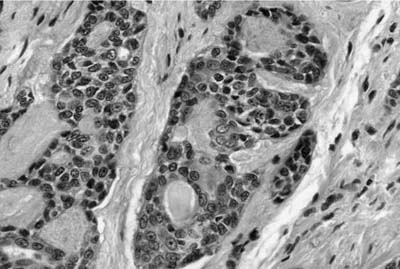

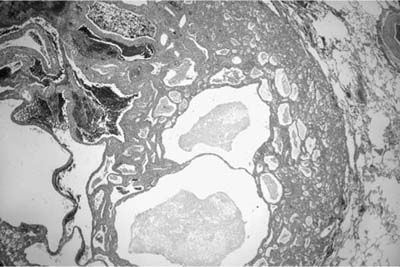

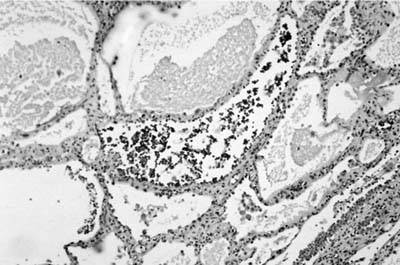

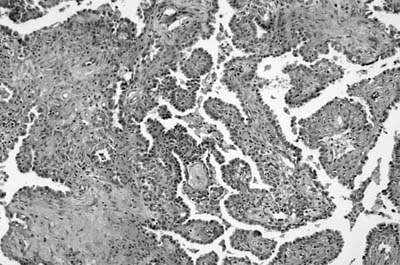

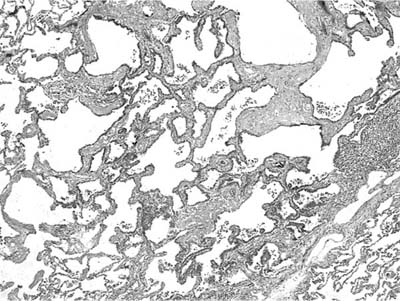

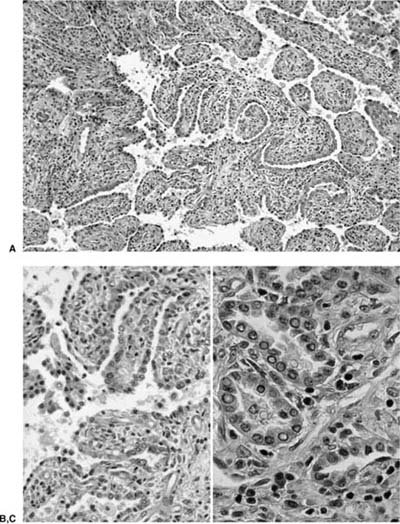

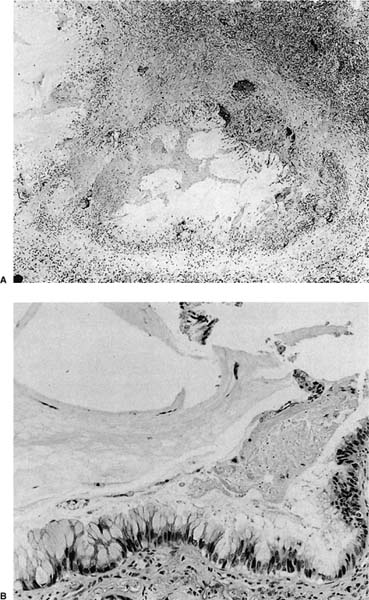

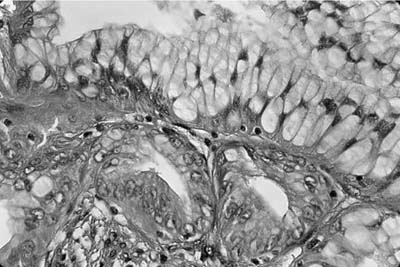

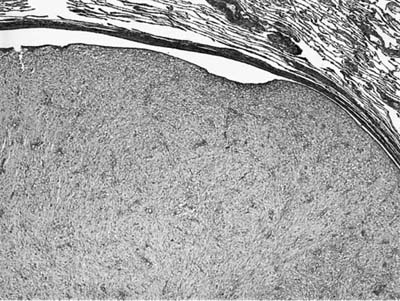

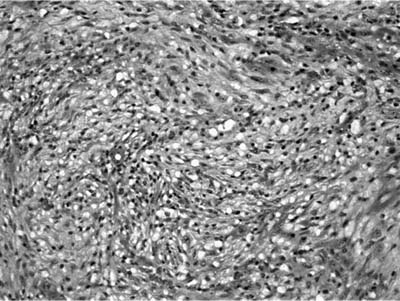

Invasive papillomatosis refers to extension of the papillary proliferation into the pulmonary parenchyma.12,19–21 This can lead to complex exophytic and endophytic mass lesions, which are frequently cystic, and associated with bronchiectasis and obstructive changes. Microscopically, relatively bland squamous epithelium may extend from alveolus to alveolus through the pores of Kohn (Fig. 18–1). Advanced cases of invasive papillomatosis may show exuberant exophytic and endophytic papillomas involving the trachea, bronchi, and lung parenchyma with mixtures of bland squamous epithelium and epithelium with varying degrees of dysplasia. Progression to squamous carcinoma occurs rarely, and its histologic recognition may be very difficult (Fig. 18–2). Cytologic features of malignancy are helpful, as are the presence of dyskeratotic foci and abundant keratinization. With or without the development of frank malignancy, invasive papillomatosis is typically fatal.

Glandular and Mixed Papillomas

Glandular papillomas are papillary tumors covered with ciliated and nonciliated columnar cells as well as nondescript cuboidal cell and goblet cells.11 In some cases squamous elements may also cover the papillary fronds (mixed papillomas). Both are generally solitary and occur in the bronchi of adults. Distinction from mucoepidermoid carcinoma may be difficult on small biopsies, but the papillomas lack intermediate cells and solid areas of growth.

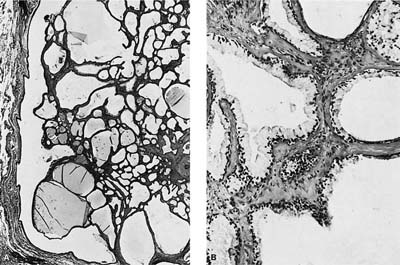

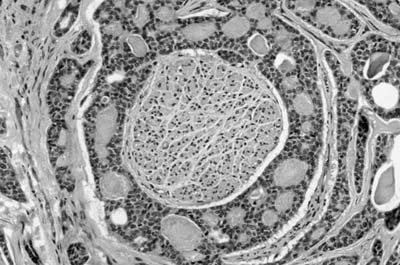

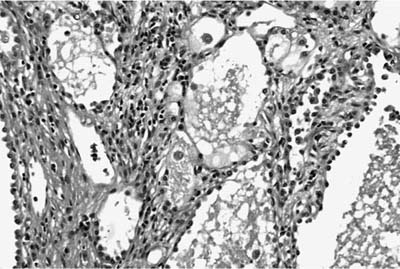

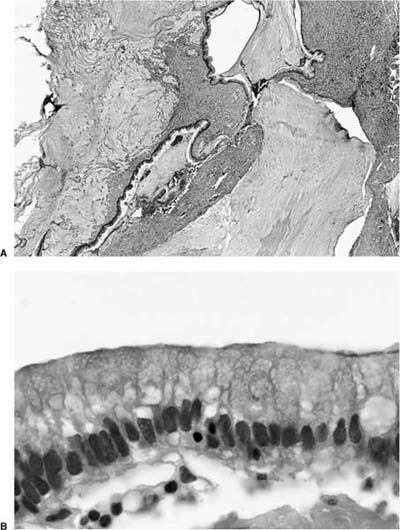

Mucous cystadenoma (mucous gland adenoma) of the bronchus is a solitary, benign, well-circumscribed multi-cystic endobronchial tumor22–25 (Fig. 18–3). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines it as “a tumor of the tracheobronchial seromucinous glands and ducts. Mucin-filled cysts, tubules, glands and papillary formations are lined by a spectrum of epithelium including tall columnar cells, flattened cuboidal cells, goblet cells, oncocytic cells and clear cells.”26 It is a tumor of adults, the mean age in one series being 52 years (range 25 to 67 years). It is about twice as common in women. Although patients may be asymptomatic, they usually present with symptoms of obstruction, including cough, dyspnea, pneumonia, and occasionally hyperinflation, due to a ball-valve effect. The tumors may be identified radiographically as a mass, but postobstructive changes may make it appear as though the process is primarily parenchymal. Complete removal is curative.

FIGURE 18–1 Invasive squamous papillomatosis. Squamous epithelium can be seen spreading from one alveolar space to another through pores of Kohn.

The tumors are usually well circumscribed and predominantly exophytic, but may have an endophytic component. Grossly, these tumors are smooth-surfaced, round, and polypoid. Microscopically, cystic change is usually prominent, and they can vary greatly in size and shape. The cysts usually occur in one of two patterns, predominantly glandular and tubulocystic, or papillocystic. A variety of cell types line the spaces, from tall columnar to flattened cuboidal and focally stratified cells, to oncocytic-like goblet cells and clear cells.

The main tumor in the differential diagnosis is low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma. In contrast to mucoepidermoid carcinoma, the mucous gland adenoma lacks intermediate cells, but may have goblet cells, so the distinction can occasionally be difficult. On small biopsies, the distinction may not be possible.

FIGURE 18–2 Squamous carcinoma arising in association with papillomatosis. Note crowding of nuclei and degree of cytologic atypia. The process is frequently cavitary.

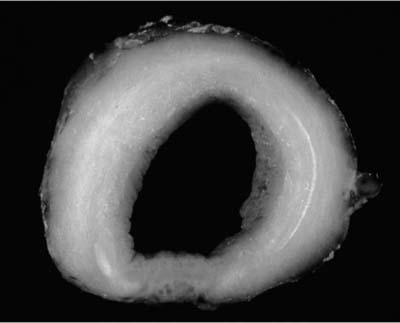

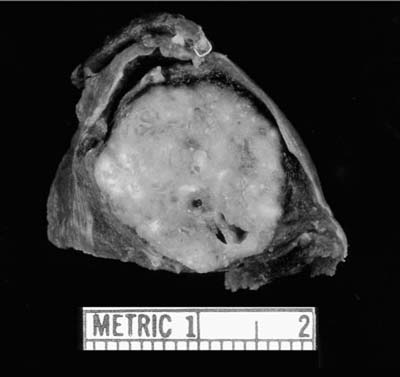

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is the most common submucosal bronchial gland tumor representing about 38 to 58% of all such tumors.27–30 It is the second most common primary tumor of the trachea31 (Fig. 18–4). These tumors may arise in the lung parenchyma in ~10% of cases.32,33 These tumors grow in an infiltrative pattern along the walls of the bronchi or trachea, but they may also present as intraluminal polypoid masses. They are most common in middle age but can occur throughout the entire span of adulthood. There is no sex predilection. In addition to obstructive symptoms, systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, and weight loss are not unusual. Chest radiographs more often show evidence of obstruction than a mass. As with adenoid cystic carcinoma that arises elsewhere, extensive local, particularly perineural, invasion makes local recurrence after surgical excision common. Extension into the mediastinum may occur, but distant metastases are rare. The tumors may respond to radiotherapy but are not cured by this modality. Endobronchial brachytherapy may prove useful in controlling recurrent adenoid cystic carcinoma.34

FIGURE 18–4 Adenoid cystic carcinoma involving trachea showing diffuse expansion of tracheal wall by infiltrating white tumor.

FIGURE 18–5 Adenoid cystic carcinoma of bronchus with pale myxoid stroma.

Histologically, they are identical to adenoid cystic carcinomas of salivary glands (Fig. 18–5) and grow in distinctive cribriform and tubular arrays surrounding central pseudocysts. The cystic spaces may contain mucinous material, or eosinophilic hyaline basal lamina-like material. The stroma may be remarkably myxoid or hyalinized. Two cell types are present: darkly staining lining cells and myoepithelial cells. The cords and nests of tumor cells tend to invade in relatively orderly, concentric bands around airways, vessels, and nerves (Fig. 18–6).

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the second most common submucosal gland tumor, accounting for about one third of all such tumors.22,27,28 Most of these tumors occur in central bronchi and only occasionally in the trachea.22,27,28,35 These tumors occur over a very broad age range (4 to 78 years) and are one of the more common epithelial malignancies in children (~14% of the total36–40). Nearly half of affected patients are younger than 30 years.41 There is no sex predilection. Common presentations include those related to local obstruction. Systemic symptoms are unusual. As with adenoid cystic carcinomas, chest radiographs more often show obstructive findings than a mass.

FIGURE 18–6 Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the bronchus infiltrating around nerve.

FIGURE 18–7 Low-grade tracheal mucoepidermoid carcinoma forming intraluminal polypoid mass.

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the lung are classified as either low or high grade, with the grade correlating closely with prognosis.41,42 High-grade tumors are not only locally aggressive, but also frequently metastasize to bones, skin, and brain.42–44 Almost all mucoepidermoid carcinomas of the lung in children are low grade with an excellent prognosis.45 In adults, patients with low-grade tumors typically survive for many years after diagnosis, whereas those patients with high-grade tumors often die within 1 to 2 years.28

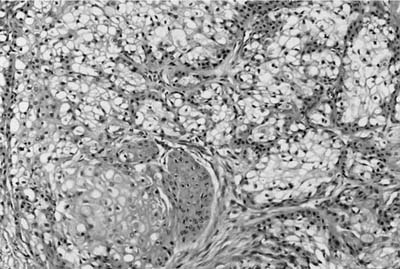

Grossly, low-grade tumors tend to be polypoid endotracheal or endobronchial nodules (Fig. 18–7). They may have a glistening mucoid cut surface in which cystic spaces may be appreciated. High-grade tumors are less often solely polypoid and are frequently invasive. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is a tumor characterized by a mixture of squamoid cells, mucus-secreting cells, and cells of intermediate type. Low-grade lesions consist of relatively abundant, well-formed mucous glands and mucus-secreting goblet cells with adjacent nests of squamoid cells (Fig. 18–8). Pleomorphism, necrosis, mitoses, and significant keratinization are lacking in the low-grade tumors. High-grade tumors show sheets of poorly differentiated squamoid cells with fewer glands. Pleomorphism, necrosis, mitoses, and more obvious foci of keratinization are characteristic of high-grade tumors. High-grade mucoepidermoid carcinomas may sometimes be difficult to distinguish from adenosquamous carcinomas. Helpful features include the intimate admixture of cell types, an endobronchial location, transition areas from a low-grade tumor and a lack of in situ component and keratinization with pearl formation. This distinction may not be of great practical importance because both tumors carry a poor prognosis.41,42,46

FIGURE 18–8 Low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma with numerous goblet cells.

Other salivary gland–derived tumors arising in the bronchial glands are very rare, but have morphologic features of similar tumors in the salivary glands. The term oxyphilic adenoma has been used indiscriminately in the past.47 Some oxyphilic tumors are bronchial carcinoids with an oncocytic feature.48,49 The term should be reserved for those tumors with granular cytoplasm due to mitochondrial hyperplasia.22,50 Acinic cell carcinomas with large periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)–positive granules51–55 have been reported in the bronchi and lung, as have pleomorphic adenomas (mixed tumors).22,56,57 The possibility of a metastasis from a salivary gland tumor must remain in the differential of pulmonary pleomorphic adenoma. The salivary gland surgery may have occurred in the remote past.

Yousem58 described two cases of unusual adenosquamous carcinoma with amyloid-like stroma that were probably of bronchial gland origin and that had features of the malignant dermal analogue tumors of the major salivary glands. These carcinomas showed both squamous and glandular differentiation associated with an abundant, waxy, hyaline, eosinophilic stroma that resembled amyloid, although special stains and ultrastructural studies confirmed that instead it was basement membrane–like material admixed with collagen. Other features included intraluminal mucin and immunohistochemical evidence of myoepithelial differentiation. Although follow-up was only 6 months and 5 months, respectively, both patients were without recurrence.

Epithelial Tumors of Pulmonary Parenchyma

Alveolar adenomas are rare benign tumors initially reported as lymphangiomas.59 Yousem and Hochholzer60 were the first to recognize them as neoplasms of alveolar epithelium and septal mesenchyme. The tumors occur primarily in adults of both sexes, and in the two largest series60,61 the mean age was 55 years (range 39 to 74 years). The vast majority of patients present with asymptomatic solitary peripheral nodules detected incidentally on chest radiograph. The tumors are clinically benign and do not recur after excision.

The WHO defines the alveolar adenoma as “a solitary nodule in the periphery of the lung consisting of a network of spaces lined by a simple low cuboidal epithelium. The stroma can range from thin, inconspicuous connective tissue to broad accumulations of spindle cells, sometimes in a myxoid matrix.”26 Grossly, the tumors are usually well demarcated and are sometimes reported to “pop out” of the parenchyma when incised. They range in size from 1.1 to 6.0 cm in diameter (mean 2.2 cm). Cut surfaces tend to be described as lobulated and multicystic, and somewhat gelatinous in character.

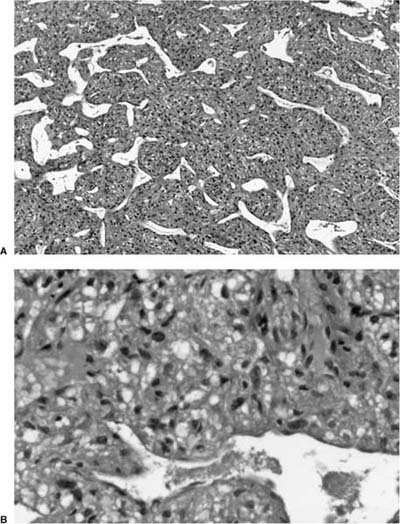

Microscopically, the tumors are also easily distinguished from the surrounding parenchyma and may compress it (Fig. 18–9). Some tumors may gradually merge with the surrounding lung. The tumors are sieve-like on low power and are composed of variable-sized cystic spaces, some quite large (Fig. 18–10). In some areas the architecture may be cribriform. The cysts may be filled with PAS-positive proteinaceous material and occasionally red cells. Papillary projections are generally not seen. The spaces are lined by a single layer of cells that resemble reactive type II pneumocytes, but they do not tend to have the prominent nucleoli often seen in such cells. The cells may impart a hobnail-like appearance to the epithelium. They have pale to slightly eosinophilic finely vacuolated or foamy cytoplasm. Rare mitotic figures may be observed, but usually at a rate less than 1 in 10 high-power fields. The interstitium is of variable thickness and consists of a myxoid matrix with fibroblast-like cells that can have oval or elongate nuclei (Fig. 18–11). The lining cells are generally keratin, thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1), and surfactant apoprotein A and B positive, and negative for CC10, a Clara cell antigen. This supports the contention that the cells are differentiating as type II pneumocytes. The interstitial cells show features of fibroblasts on electron microscopy (EM). It is not clear whether both elements are neoplastic. Interestingly, a clonal cytogenetic translocation of der (16) t (10;16)(q23:24) has been identified in ~20% of these tumors.62

FIGURE 18–9 Alveolar adenoma well demarcated from the adjacent parenchyma.

FIGURE 18–10 Alveolar adenoma with variable-sized cysts, some filled with proteinaceous material and some containing (probably extravasated) red blood cells.

The differential diagnosis includes atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (see below) and a true lymphangioma. When in doubt, immunoperoxidase stains for both vascular and type II pneumocytes facilitate distinguishing these entities.

Sclerosing hemangioma, so-called sclerosing pneumocytoma, is a benign lung neoplasm thought to be derived from incompletely differentiated respiratory epithelium.63–70 It typically presents as a slowly enlarging asymptomatic solitary pulmonary nodules. About 5% of reported patients have had multiple lesions.71–74 Sclerosing hemangioma is more common in women than men by a ratio of 4:1 to 5:1. The mean age at diagnosis is usually the fifth decade, although a wide age range has been reported, including in children. Symptomatic patients most commonly complain of hemoptysis or vague chest discomfort. Rare examples of metastases to regional lymph nodes have been reported. Follow-up in a small number of patients currently being reported has indicated that such metastases do not seem to impact long-term survival at a mean follow-up period of 4.8 years.75,76

FIGURE 18–11 Alveolar adenoma with prominent septal mesenchyme. The lining cells are low cuboidal and have very bland cytologic features.

FIGURE 18–12 Sclerosing hemangioma. Note the variegated surface reflecting the histologic variability of this tumor.

Grossly, sclerosing hemangiomas tend to be well circumscribed peripheral subpleural nodules (Fig. 18–12) with average diameters of 2 to 3 cm (range 0.4 to 8.2 cm). Occasional tumors may involve pleural surfaces. The WHO defines sclerosing hemangioma as “a tumour of uncertain type with a distinctive constellation of histologic findings, including solid, papillary, sclerotic and hemorrhagic patterns. Hyperplastic type II pneumocytes line the surface of the papillary structures. The interstitial epithelioid cells are bland and uniform with pale cytoplasm. Cholesterol clefts, chronic inflammation, xanthoma cells, hemosiderin, calcification, laminated scroll-like whorls, necrosis and mature fat may be seen.”26

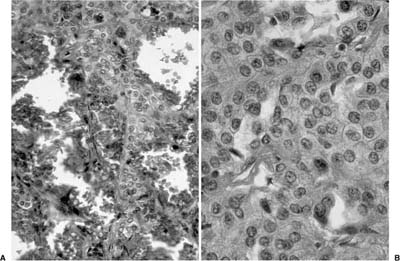

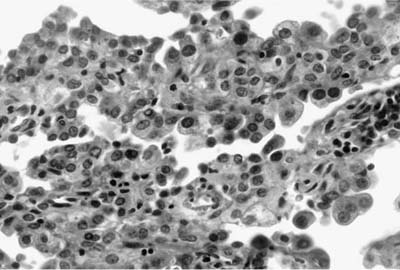

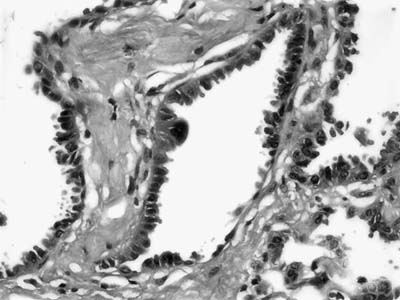

As emphasized in this descriptive definition, the histologic hallmark of sclerosing hemangioma is a heterogeneous variegated appearance resulting from a mixture of solid, hemorrhagic, papillary, and sclerotic patterns. Two populations of epithelial cells can be identified: (1) surface cuboidal cells with phenotypic features of pneumocytes or Clara cells, and (2) pale interstitial polygonal or round cells of uncertain histogenesis (Figs. 18–13 and 18–14). Although controversial, the bulk of the evidence suggests that polygonal round cells represent the neoplastic population. Round cells have bland cytology with centrally located round to oval nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and pale eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm with distinct cytoplasmic borders. Mitotic figures are rare. The cells are typically arranged in a solid or papillary growth pattern with an associated collagenous (sometimes strikingly sclerotic) stroma containing variable numbers of pseudovascular blood-filled spaces. Hemosiderin pigment may also accompany the blood-filled spaces. Cells that line the surface of the papillae are low cuboidal to columnar in nature (Fig. 18–15). An associated inflammatory infiltrate is common and frequently includes conspicuous numbers of mast cells.

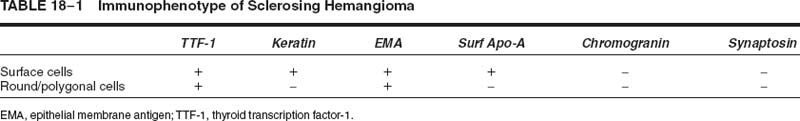

The histogenesis of sclerosing hemangioma has been a matter of considerable interest since Liebow and Hubbell64 first suggested in 1956 that they represented endothelial-derived neoplasms. A mesothelial origin was suggested in 1983 based on a combination of ultrastructural, histochemical, immunohistochemical, and electrophoretic studies.77 Other studies have convincingly demonstrated its epithelial phenotype.78–86 In a critical review of 21 cases, Rodriguez-Soto and colleagues87 demonstrated consistent immunoreactivity only for epithelial membrane antigen in lesional cells with focal immunoreactivity for keratin in a minority of cases. All other markers tested were consistently negative, including S-100 protein, smooth muscle actin, and various neuroendocrine markers. More recent studies have demonstrated immunoreactivity for TTF-1,88 a specific marker for both thyroid and lung epithelium, and epithelial membrane antigen in both surface and round/polygonal cells. Staining for keratin, surfactant apoproteins, and Clara cell antigen was limited to cuboidal surface cells (Table 18–1).

FIGURE 18–13 Sclerosing hemangioma with solid and papillary growth pattern.

FIGURE 18–14 Sclerosing hemangioma with hemorrhagic foci (A) and pale interstitial cells (B).

The main differential diagnosis includes other low-grade epithelial neoplasms, including pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Careful attention to the characteristic variegated histology should be helpful in most cases. Immunoperoxidase stains can be useful in distinguishing sclerosing hemangioma from carcinoid tumors, particularly in small biopsies, in that the latter are positive for neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin.

FIGURE 18–15 Sclerosing hemangioma. Low cuboidal cells line the surface of the papillae.

Micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia (MNPH) of type II pneumocytes is the term coined by Popper et al89 for a peculiar pneumocyte hyperplasia first illustrated by Spencer.90 It can occur sporadically, but is closely associated with lymphangioleiomyomatosis, with or without tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC).91–95

The WHO defines micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia as “a multifocal micronodular proliferation of type II cells with mild thickening of the interstitium.”26

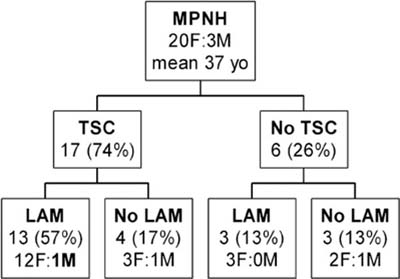

MNPH arises more commonly in women (Fig. 18–16). Age ranges between 21 and 57 years. Although MNPH can be an isolated finding, it is most commonly found in patients with TSC, usually in association with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. The only proven man to have lymphangioleiomyomatosis also had MNPH.

Pulmonary symptoms in patients with MNPH, although common, are likely attributable to the associated lymphangioleiomyomatosis. However, two patients without lymphangioleiomyomatosis did present with respiratory distress and pneumothorax. Nodular or reticulonodular infiltrates are seen on chest computed tomography scan. This process is benign with no deaths attributed MNPH. It does not seem to be a precursor to (bronchioloalveolar) adenocarcinoma.

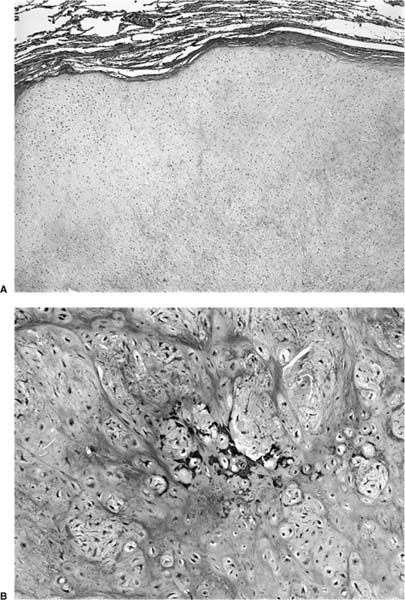

MNPH is always multiple, and the foci of involvement are randomly distributed in the lung parenchyma, ranging between <1 and 8 mm. They can be appreciated grossly.96 They are sharply circumscribed from the adjacent normal pulmonary parenchyma, and usually do not gradually merge with it (Fig. 18–17), as can be seen with atypical adenomatous hyperplasia or bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. These minute nodules are composed of flat to cuboidal cells lining mildly thickened, fibrotic alveolar septa. The cells are usually very bland but can focally show mild cytologic atypia, with increased nuclear size and prominent nucleoli. The epithelial cells stain diffusely for keratin, surfactant, and TTF-1, and are negative for Clara cell protein. This immunohistochemical profile supports the interpretation that it is a type II pneumocyte proliferation. In contrast to lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), the cells are negative for HMB-45 and estrogen receptor protein (ER)/progesterone receptor protein (PR).

The differential diagnosis includes lesions composed of or mimicking type II pneumocytes, including atypical adenomatous hyperplasia and nonmucinous bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, sclerosing hemangioma, and a papillary adenoma of type II pneumocytes.97–99

Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia is currently the preferred term for lesions that have some but not all of the criteria for bronchioloalveolar adenocarcinoma. Synonyms include bronchioloalveolar cell adenomas, alveolar epithelial hyperplasia, atypical alveolar cuboidal cell hyperplasia, alveolar atypical hyperplasia, and atypical bronchioloalveolar cell hyperplasia.97,100 The WHO defines these as “a focal lesion, often 5 mm or less in diameter, in which the involved alveoli and respiratory bronchioles are lined by monotonous, slightly atypical cuboidal to low columnar epithelial cells with dense nuclear chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli and scant cytoplasm.”26 These minute circumscribed lesions of the lung are not uncommonly encountered as an incidental finding, although with special fixation they may be more readily identified.97 The relatively sharp circumscription of these lesions and the absence of evidence of previous or ongoing parenchymal injury suggest that these lesions are neoplastic or “preneoplastic” rather than reactive.97,101

FIGURE 18–16 Distribution of micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) with and without lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) (compiled from multiple series).

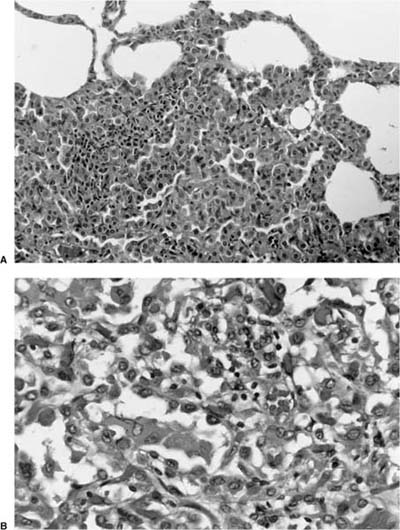

FIGURE 18–17 Micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia appears separate from adjacent normal parenchyma (A) and is composed of hobnail cells with bland cytologic features and a modest amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm (B).

It has been suggested that these lesions may be early, precursor lesions for pulmonary adenocarcinoma analogous to colon polyps.102–108 In a series of 67 cases with such lesions identified from lobectomy and pneumonectomy specimens, Weng et al109 found no association between these lesions and a smoking index. However, such lesions were associated in men with cases of primary adenocarcinoma of the lung significantly more often than with tumors metastatic to the lung, which suggests that they may be precursor lesions for adenocarcinomas of the lung.105,110 Additional evidence that these lesions are neoplastic comes from Nakayama et al.111 These investigators noted continuity of some of these lesions with frank adenocarcinomas and found that these lesions showed nuclear DNA content greater than that of reactive type II pneumocytes and equal to that of small well-differentiated adenocarcinomas. In addition, these lesions had aneuploid stem lines in 53.8% of cases but had DNA histograms in which aneuploid cells were less frequent than in control adenocarcinomas. Although these observations indicate that atypical adenomatous hyperplasia is likely neoplastic, they do not indicate whether they should be considered benign “adenomas” or small well-differentiated carcinoma.

Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia was found incidentally in 9.3% of lung cancer resection specimens97 and 2.7% of autopsies lungs in a large Japanese population.112 The nodules range in size from 0.1 to 0.7 cm in greatest dimension, with most being less than 0.3 cm. Most often a solitary lesion is identified, but up to five separate lesions may be noted. Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia consists of low cuboidal, rounded, or domed cells with abundant cytoplasm growing in a lepidic fashion on intact alveolar septa (Fig. 18–18). The nuclei are often hyperchromatic and may be smudged (Fig. 18–19). Intranuclear inclusions may be present. Mild fibrotic interstitial thickening may be present, but interstitial inflammation, central scars, and invasion by atypical cells is absent. Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia lesions typically gradually merge with normal surrounding alveolar walls. Ultrastructurally, the cells have features of type II pneumocytes including lamellar bodies.

FIGURE 18–18 Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia composed of slightly thickened alveolar septa.

In distinction from MNPH, the cells are slightly more atypical, with increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios. The distinction between atypical adenomatous hyperplasia and bronchioloalveolar carcinoma is not well defined. Marked cytologic atypia and a diameter greater than 5 mm are both features that have been suggested as useful. Cell density along the alveolar wall is also greater in bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. Even if atypical adenomatous hyperplasia could be detected in vivo (and with improved imaged techniques this is certainly possible), there is no indication that eradication of these grossly barely perceptible lesions has any benefit to patients. Conceivably, the presence of multiple foci of atypical adenomatous hyperplasia might put a patient at higher risk of carcinoma, but this has not been established.

FIGURE 18–19 Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia. Alveolar walls are lined by hobnail cells with moderate nuclear hyperchromatism and atypia.

FIGURE 18–20 Papillary adenoma of type II pneumocytes (A–C). The papillae are complex and branching. Bland epithelium covers fibrous papillary cores.

The papillary adenoma is a rare benign lesion that presents as a solitary nodule in asymptomatic patients. Naturally occurring and experimentally induced papillary type II pneumocyte and Clara cell adenomas of the lung are common in mice.113–115 In humans they have been reported in children and adults.116,117 They are composed of true papilla with connective tissue cores lined by cytologically bland cuboidal cells.118–120

These tumors vary in size from 1 to 5 cm. They do not appear to arise from major bronchi, although they may occasionally extend into small peripheral bronchi. Grossly, papillary adenomas are unencapsulated, well-circumscribed, soft, yellow, tan, or brown masses with granular cut surfaces without necrosis or hemorrhage. Microscopically, they consist of uniform, cytologically benign, nonciliated, cuboidal to peg-shaped columnar cells lining multiple branching papillary fronds with generally delicate fibrovascular cores (Fig. 18–20). The epithelium may be in a single row or have a pseudostratified appearance. Oncocytic change may occasionally be present in the epithelial cells and in one case was a prominent feature. The papillary cores may sometimes show a hyalinized stroma. More solid or glandular foci of epithelium may be present, as may scars and dystrophic calcifications. These cells, by immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies, show mostly type II pneumocyte differentiation but can also show Clara cell differentiation.11,73,116–119

These tumors may be distinguished from primary and metastatic papillary carcinomas by the absence of cytologic atypia, high mitotic rate, invasion, and necrosis.121 In addition, psammoma bodies and mucin production are not present.

Mucinous cystadenoma/cystic tumor of borderline malignancy: There is a spectrum of mucinous neoplasms variously reported as mucinous cystadenomas, pulmonary mucinous tumors of borderline malignancy, and mucinous or colloid carcinoma. In 1978 Sambrook Gowar122 described the occurrence of a multilocular cyst in a 68-year-old woman. Spencer123 and Dail124 both briefly described additional cases. They considered these neoplasms the counterpart of mucoceles of the appendix and favored the designation cystadenoma. In 1990 Kragel et al125 described two additional cases as mucinous cystadenoma, and in 1991 Graeme-Cook and Mark126 studied 11 cases that they described as borderline mucinous cystic tumors, with analogies to ovarian neoplasia. Since then other reports have appeared, and the consensus that appears to be emerging is that there is a spectrum of such lesions.

Mucinous cystadenomas tend to be unilocular cystic lesions with a fibrous wall lined by well-differentiated, presumably benign columnar mucinous epithelium. The few cases reported have occurred in adult smokers, but complete resection apparently results in cure. Grossly, these tumors range in size from 0.8 to 15 cm in diameter, with the great majority 6 cm or less in diameter. They are well-circumscribed macrocysts filled with abundant mucin and lined by a thin fibrous wall. Most are peripheral and do not communicate with or obstruct bronchi.125–127 Microscopically, nonciliated columnar cells line the cysts with hyperchromatic basal nuclei and abundant apical mucin (Fig. 18–21). The epithelium may be in a single uniform row or stratified with infoldings. It may be focally denuded. The epithelium may show variable degrees of cytologic atypia and crowding. In those lesions characterized as of borderline malignancy, greater degrees of cytologic atypia may be present as well as small foci of carcinoma. The fibrous wall may contain an inflammatory infiltrate. Foci of extravasated mucin with foreign-body giant cell reaction may be present in the adjacent lung tissue, that is, pseudomyxoma pulmonis (Fig. 18–22), and should not be confused with invasion. Although seeding of the pleura has been reported in one patient,122 she continued to be asymptomatic for 5 years. Long-term follow-up in many of the patients has failed to disclose recurrence or metastasis even when small foci of adenocarcinoma are present. A discussion of malignant mucinous lesions appears later in this chapter.

Mucinous (colloid) adenocarcinoma is characterized by the presence of tumor cells floating in pools of mucin. This feature may be seen as a focal pattern or a pure histologic pattern. In 1992 Moran et al128 presented 24 cases of primary mucinous (colloid) carcinoma of the lung. The patients were between 33 and 81 years of age (median 57 years), including 15 men and 9 women. The lesions were all discovered incidentally on chest x-ray and varied in size from 0.5 to 10 cm in greatest dimension. Grossly, the tumors were poorly circumscribed, soft tan to gray, and mucoid. They consisted of intraalveolar pools of mucin containing small clusters of atypical cells floating in the mucin and foci of neoplastic columnar epithelium lining scattered alveoli. Seven cases showed areas of solid well-differentiated malignant glands. A constant feature in their cases was the presence of small nests of tumor cells and individual cells, some with signet ring cell features, floating in the mucus, creating a picture indistinguishable from colloid carcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract or other organs. Of 19 patients for whom follow-up was reported, 58% were alive, 2 with metastases or recurrences. Eight patients died of their tumor with bone and brain metastases.

Signet ring cell carcinomas are well-recognized variants of adenocarcinoma in the gastrointestinal tract and in the breast. The existence of a primary lung tumor with these features is less well known. In 1989 Kish et al129 described five cases of primary lung neoplasms as mucinous adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells, and there have been a few sporadic reports since.128,130–133

Castro et al132 reported the largest series. They defined signet ring cell carcinomas as those showing greater than 75% signet ring cells. Signet ring cells were defined as cells containing large mucin droplets that displaced the nucleus to the edge of the cell. They identified 12 such cases in a review of 320 cases (3.75%) of adenocarcinomas diagnosed over a 6-year period. Three more were identified in consultation settings, for a total of 15; 12 were men and 3 were women, ages 30 to 75 years (mean 53 years), of whom 6 were smokers. None had a previous malignancy or had any detected during workup. Clinical symptoms included weight loss, hemoptysis, nausea, vomiting, and chest pain. Eight tumors were located centrally and seven in the periphery of the lung. The tumors ranged in size from 1.8 to 8.0 cm. The authors described the presence of the signet ring cells in two histologic settings. The majority of the tumors had an acinar arrangement (12 cases), where the tumors were composed of tightly packed nests of cells separated by thin strands of connective tissue, or arranged in clusters filling alveolar spaces. Signet ring cells were interspersed among malignant cells with more granular cytoplasm. The diffuse pattern was characterized by a haphazard distribution or cord-like arrangement of tumor cells, often with more atypical cytology than that seen in the first variant. All tumors also had areas of more conventional adenocarcinoma, which by definition comprised less than 25% of the tumor.

Follow-up information was available in 11 of Castro et al’s patients. Six had died within 12 months, and five were alive 5 to 36 months after initial diagnosis. Unfortunately, the authors give no staging information.

FIGURE 18–21 Mucinous cystadenoma. (A) Low-power view shows a thick fibrous wall with a mucus-filled cystic space and granulomatous inflammation in the lining. (B) High-power view shows columnar goblet cells with basal nuclei (A, ×50; B, ×200). (Courtesy of Dr. William D. Travis, Memorial Sloan Kettering, NY.)

The main differential diagnosis to be considered is metastatic disease, usually of gastrointestinal origin. Table 18–2 shows the immunohistochemical profile of these tumors. Apart from metastatic carcinomas, the differential diagnosis includes other primary lung tumors that can show signet ring cell morphology at least focally. These include mucinous (colloid) carcinomas, acinic cell carcinoma, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Acinic cell carcinomas may have cells that resemble signet ring cells, but the tumor cells lack mucin, and histochemical stains could be used to make the distinction.

Mucoepidermoid carcinomas may also have cells that mimic signet ring cells. Since low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinomas do have a relatively good prognosis, the distinction is important. Mucoepidermoid carcinomas usually arise centrally, and nearly half occur in patients under 30 years of age. They typically present as endobronchial masses and are usually well circumscribed. The presence of squamous and intermediate cells and the lower grade cytology of the mucous cells should be helpful in distinguishing them from signet ring carcinomas.

FIGURE 18–22 Mucinous cystadenoma of borderline malignancy with pseudomyxoma pulmonis (A). The lining cells have moderate cytologic atypia and hyperchromatic (B).

Mesenchymal Tumors

Hamartoma has been given many designations in the past, including chondroma, adenochondroma, chondromatous hamartoma, chondroid hamartoma, fibroadenoma, lipochondroadenoma, mixed pulmonary tumor, and benign mesenchymoma.134,135 They account for 77% of benign lung tumors136 and may be found in as many as 0.25% of autopsies.137 Cytogenetic studies have identified recombinant chromosomal bands in these tumors, supporting the current view that hamartomas are clonal mesenchymal neoplasms.138

Hamartomas occur predominantly in older men (mean age 61 years, range 17 to 90 years), by a factor of 2.139,140 The peak decade of occurrence is the seventh.141 Most hamartomas are solitary and asymptomatic, although they may rarely be multiple,142 or associated with other benign hamartomatous neoplasms.143 Imaging shows them to be well-circumscribed, lobulated, subpleural (usually) masses sometimes with calcification. The presence of fat may be seen on computed tomography and is very helpful diagnostically.144,145

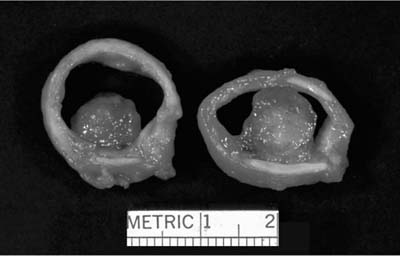

Greater than 90% are peripheral, intraparenchymal tumors. The remaining occur centrally, as endobronchial polypoid masses.141 In most series, the average diameter is 2 to 3 cm, but they may grow as large as 6 cm. Grossly, they are well-circumscribed, lobulated, and shell out easily from the surrounding lung (Fig. 18–23). The cartilaginous and fatty nature of the tumors may be appreciated.

Marker | Positive Cases | Percent |

|---|---|---|

Pancytokeratin | 9 of 9 | 100 |

Cytokeratin 7 | 3 of 6 | 50 |

Cytokeratin 20 | 0 of 6 | 0 |

TTF-1 | 6 of 6 | 100 |

CEA | 9 of 9 | 100 |

ER | 0 of 6 | 0 |

PR | 0 of 6 | 0 |

GCDFP-15 | 0 of 6 | 0 |

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; ER, estrogen receptor protein; GCDFP-15, gross cystic disease fluid protein; PR, progesterone receptor protein; TTF-1, thyroid transcription factor-1.

From Castro et al.132

Most hamartomas consist of various combinations of mature hyaline cartilage, fibromyxoid stroma, and mature adipose tissue. In one large study, mature cartilage was the predominant component (>50%) in 51% of cases, whereas a fibromyxoid component was predominant in 11%141 (Fig. 18–24). Adipose tissue predominated in only 2%. Rare examples may be composed of only cartilage or fibromyxoid tissue. In the typical example, a cartilaginous core is surrounded by a rim of loose myxoid or fibrous tissue. Calcification is seen in 15% of cases and bone in 5%. Entrapped nonneoplastic epithelium giving rise to variably wide clefts is incorporated into 87% of tumors and appears bronchiolar in nature. The cells are cuboidal to columnar and may have cilia or mucin, or show foci of goblet cell metaplasia (Fig. 18–25). Smooth muscle cells may be seen at the periphery of the tumors as well.

Immunohistochemically, the stromal cells may express S-100 protein, desmin, actin, smooth muscle actin, or glial fibrillary acidic protein,146 but do not express CD34 or HMB-45.

The differential diagnosis includes the pulmonary chondroma and mixed tumors, both primary and metastatic. Primarily fibromyxoid tumors must be distinguished from inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors.

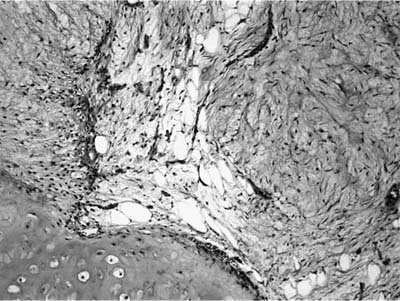

Chondromas are benign cartilaginous neoplasms that occur in patients with the so-called Carney triad of gastric stromal tumors, pulmonary chondroma and paraganglioma.147–149 Such tumors have also been called osteochondromas. It is thought they are distinct from ordinary pulmonary hamartomas. Patients with chondromas are usually asymptomatic young women, who may or may not have other signs and symptoms of the triad at the time the chondroma is discovered. On imaging the tumors are usually multiple and have “popcorn” calcification. The tumors range in size from 0.5 to 12 cm in diameter and are usually easily enucleated from surrounding lung. Histologically, they consist of well-differentiated cartilage, often with foci of calcification (Fig. 18–26). In contrast to pulmonary hamartomas, they do not contain fat, spindle cells, or entrapped pulmonary epithelium. The differential diagnosis also includes metastatic chondrosarcoma, but the distinctive settings of chondrosarcoma and chondroma usually facilitate distinguishing them.

FIGURE 18–23 Hamartoma with typical multilobulated appearance and glossy surface, distinct from the surrounding lung.

FIGURE 18–24 Hamartoma with its three prime components: cartilage, fibromyxoid stroma, and adipose tissue.

Clear cell tumor of the lung, also known as “sugar” tumor of the lung, is a very rare and somewhat controversial entity. Liebow and Castleman initially recognized the tumor in 1963. Their experience with 12 cases was published in 1971,150 using the modified term benign clear cell (“sugar”) tumor to capture the fact the clear cytoplasm was due to an abundance of glycogen (sugar). The WHO defines the tumor as one “composed of cells with clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm which contains abundant glycogen. Thin-walled blood vessels without a muscular coat are characteristic.”26

The tumor is slightly more common in women and has been reported over a wide age range, 8 to 67 years, with the median being 51 years. The tumor is usually identified incidentally on chest imaging. The tumors are generally small, the median diameter being 2.0 cm (range 1 to 6.5 cm). The tumor usually arises within the lung parenchyma, but has rarely been observed in the trachea.151 With rare exception152 the tumors behave in a benign fashion and patients are cured after excision.

Grossly, the tumors appear red-tan in color and are usually without hemorrhage or necrosis.153,154 They are not yellow, in contrast to metastatic renal cell carcinoma, from which it must often be distinguished. Microscopically, they are circumscribed but not encapsulated and are composed of (1) plump, epithelioid cells with abundant clear to lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm and distinct cell borders with (2) round, medium-sized nuclei with occasional moderately sized nucleoli, and (3) a zellballen- type architecture with small tumor nests separated by thin fibrous septa containing capillaries (Fig. 18–27). Eosinophilic cytoplasmic intranuclear inclusions are frequently present. The cells contain abundant glycogen, as can be demonstrated by PAS stains. The cells do not contain fat, a feature that may help differentiate clear cell tumor from metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Multinucleated giant cells may be present.150,154–156 Mitotic figures are rare, and there is usually no necrosis, frank anaplasia, or vascular invasion. The stroma is scanty, and may rarely be hyalinized or calcified, the latter occasionally appearing psammomatous. Rare malignant variants have been reported, both in the lung and in other sites. No definitive criteria have been established, but numerous mitoses, significant cytologic atypia, and necrosis may all signify more aggressive behavior.153

FIGURE 18–25 Hamartoma. Entrapped epithelium shows prominent goblet cell metaplasia.

FIGURE 18–26 Chondroma with thin rim of fibrous tissue (A) and foci of calcification (B).

Most tumors stain strongly for HMB-45, weakly for vimentin, and are negative for epithelial markers such as low and high molecular weight keratin. Ultrastructurally, the cytoplasm contains both free and membrane-bound glycogen, a feature otherwise seen only in type II glycogen storage disease.157–159 The tumors usually show evidence of melanocytic differentiation in the form of premelanosomes.160

FIGURE 18–27 Clear cell tumor with prominent vascularity (A) and zellballen. On high power, the cells are clear to palely eosinophilic and have nuclei that are oval to round and may contain nucleoli (B).

The origin of “sugar” tumors of the lung has been debated. Although early studies suggested origin from smooth muscle or pericytes, neuroendocrine (Kulchitsky) cells, and epithelial nonciliated bronchiolar (Clara) or serous cells,161 later studies have noted reactivity for HMB-45 and have shown ultrastructural evidence of melanocytic differentiation.160 Expanding on the latter concepts, Bonetti et al162 proposed that clear cell tumors of the lung arise from the “perivascular epithelioid cell” (PEC) and noted that similar cells have been identified in angiomyolipomas and lymphangiomyomas and some cases of lymphangioleiomyomatosis.163

The differential diagnosis includes metastatic renal cell carcinoma and paraganglioma, tumors that can usually be distinguished from clear cell tumors on the basis of immunoperoxidase studies.

Lipomas of the lung usually arise in bronchi.164–168 Lipomas of the parenchyma or pleura are extremely rare, but have been reported.169 Almost all patients are middle-aged adults (mean age 60 years), and 90% are men. Most patients are asymptomatic, but some present with symptoms of obstruction. Multiple pulmonary lipomas have been described in association with Cowden’s disease.170 Bridge et al171 have identified amplification of chromosome 12 in a pulmonary lipoma, similar to cytogenetic abnormalities identified in lipomas from more typical locations.

Grossly, these tumors consist of yellow fat and are usually 3 to 6 cm in diameter. The endobronchial lipomas are submucosal, rounded, usually pedunculated masses covered by bronchial mucosa. As with lipomas elsewhere, they are composed of benign mature fat. Rarely, peribronchial extension through spaces between the bronchial cartilage may be seen, but this does not imply malignancy in the absence of other atypical features (Fig. 18–28).

FIGURE 18–28 Lipoma with prominent endobronchial growth.

The differential diagnosis includes pulmonary hamartoma (which by definition contains other mesenchymal elements, particularly cartilage) and angiomyolipoma. The latter may indicate the presence of tuberous sclerosis complex.96,172,173

Primary liposarcomas of the lung are vanishingly rare.174–177 Of the handful of cases in the literature, both sexes are affected equally, and the age ranges from childhood to the sixth decade. These tumors may involve the bronchi or pulmonary vasculature and have the histopathologic features of liposarcomas from other sites. As with other sarcomas of the lung, metastasis from another site should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Tumors with Muscle Differentiation

Leiomyomas primary to the lung are rare and may occur as solitary tumors. About half of the cases are endobronchial and cause cough and symptoms of obstruction. Parenchymal tumors are usually asymptomatic. Patient age ranges at presentation from childhood to the seventh decade, with an average age in the fourth decade. Women are affected about twice as frequently as men.178

Leiomyomas consist of interweaving fascicles of spindle cells that may entrap bronchiolar and alveolar epithelium and give rise to a biphasic appearance with apparent glandular spaces. Leiomyomas can generally be differentiated from other spindle cell neoplasms on the basis of desmin and muscle-specific actin immunoreactivity. Leiomyomas have a mitotic count less than 0 per 50 high-power fields, have low cellularity, lack cytologic atypia, and have prominent fibrosis or hyalinization. Differentiation from leiomyosarcoma is based on mitotic count and other features of malignancy. Gal et al179 proposed that the minimal criterion for pulmonary leiomyosarcoma should be an average mitotic rate of 1 per 10 high-power fields, similar to the criteria in other nonuterine sites, although nuclear pleomorphism, cellularity, necrosis, and hemorrhage are also worrisome features and emphasize the need for adequate sampling.

Benign metastasizing leiomyoma is the term used to describe the occurrence of multiple, bilateral pulmonary leiomyomas in women with uterine leiomyomas.180–184

The lesions occur in adult women with an average age of 47 years (range 30 to 74 years). About one third of patients are symptomatic with cough or dyspnea.

The nodules vary in size from microscopic to greater than 10 cm (Fig. 18–29). Some patients have a few nodules, but most have innumerable nodules. The nodules do not appear to have any particular anatomic predilection and appear randomly distributed. By definition the tumors are composed of bland smooth muscle cells (Fig. 18–30) that are usually well circumscribed. Some nodules may have zones of fibrosis. Mitotic activity should be low, and the presence of more than 5 per 50 high-power fields has been suggested as indicative of sarcoma.

FIGURE 18–29 Benign metastasizing leiomyoma forming multiple radiographic opacities.

FIGURE 18–30 Benign metastasizing leiomyoma forming a circumscribed intraparenchymal nodule (A). It is composed of bland smooth muscle cells (B).

There are several pathogenetic theories proposed to account for benign metastasizing leiomyoma. Many authors believe that these tumors are in fact low-grade metastatic leiomyosarcomas and that additional sampling of the original uterine tumor would have revealed previously overlooked sarcomatous areas.182–185 Some have suggested that these lesions are hormonally sensitive, nonneoplastic proliferations of pulmonary interstitial or blood vessel smooth muscle, a concept that gave rise to the term fibroleiomyomatous hamartoma.186,187 Gal et al179 have argued for this position, noting that (1) patients with this condition are younger on average than patients with leiomyosarcoma of the uterus; (2) the tumors in the lung usually lack mitotic activity, and multiple lesions are often of similar size and histology; and (3) there are multiple reports of regression following oophorectomy, pregnancy, and hormonal manipulation, and the tumor growth can be promoted by oral contraceptives.188–199 Results of comparative genomic hybridization and X-chromosome inactivation analysis of lung and uterine tumors from a patient with benign metastasizing leiomyoma revealed a balanced karyotype different from that reported in usual uterine leiomyomas or uterine leiomyosarcomas in the uterine tumors, and an identical X-chromosome inactivation pattern found in the multiple lung tumors studied, suggesting a monoclonal origin of both the uterine and pulmonary lesions.200 These data suggest that the term may indeed be accurate.

Pulmonary leiomyosarcomas are rare but are among the more commonly reported primary lung sarcomas. The tumors occur over a broad age range, including children, but they are most common in middle-aged to elderly adults. There appears to be no predilection for women.175,201–210 Survival rates of around 60% at 3 to 5 years have been reported in different series, with a combination of therapies.

Primary leiomyosarcomas of the lung occur as round, well-circumscribed solitary intraparenchymal masses up to 24 cm in diameter. Invasion of the chest wall may be present. Necrosis and hemorrhage may be seen grossly in larger tumors. About one sixth occur as polypoid endobronchial masses frequently exhibiting ulceration and hemorrhage. These tumors have histopathologic features typical of leiomyosarcomas. Gal et al179 proposed a minimum of one mitosis per 10 high-power fields to distinguish leiomyosarcomas from leiomyomas in the lung, but also pointed out that pleomorphism in the absence of increased mitoses was also a cause for concern. Vascular invasion and epithelioid features can occasionally be seen. Prognosis appears related to grade of tumor and mitotic activity may be particularly important.179,210,211 Size alone appears to be a poor predictor of survival. The differential diagnosis must include metastatic leiomyosarcomas from the uterus or other sites.

Primary rhabdomyosarcomas have been reported sporadically in children and adults.175,212,213 Most are large solid intraparenchymal tumors, although a polypoid endobronchial growth pattern has also been reported.214 Most cases are either of embryonal or alveolar type. Cytoplasmic cross-striations may be difficult to find. Ultrastructural confirmation of skeletal muscle differentiation and immunopositivity for muscle-specific actin and desmin support the diagnosis. Muscle differentiation may also be seen in pulmonary blastoma and pleomorphic carcinoma.175,215–219 Rhabdomyoblastic differentiation may also be seen as a frequent component of pleuropulmonary blastoma of childhood.220 Finally, cytologically benign striated muscle may be seen as a component of congenital pulmonary airway malformation (congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation) type 2, so-called rhabdomyomatous dysplasia.

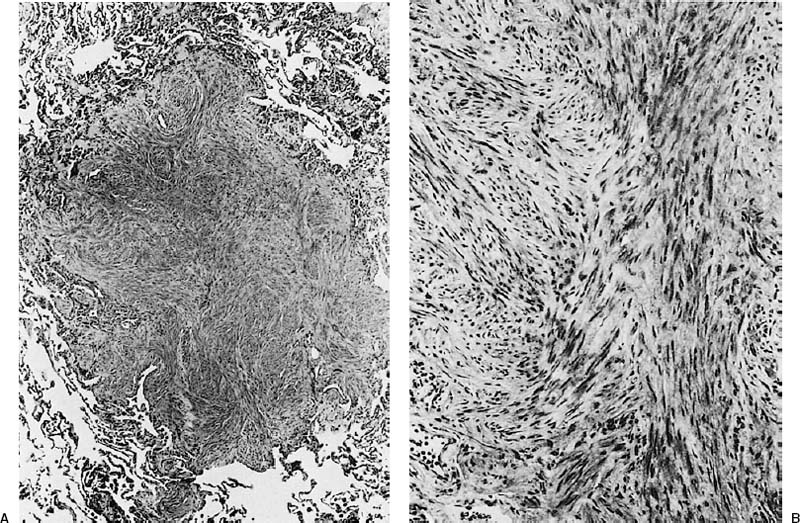

Inflammatory fibroblastic tumor is a lesion composed of fibroblasts or myofibroblasts with an accompanying infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. The lesion has had a variety of names in the past, and it is unlikely that the current WHO definition26 captures all of these entities.221–226 The array of synonyms has included frankly malignant sarcomas analogous to malignant fibrous histiocytoma of soft tissue as well as fibrous histiocytoma, inflammatory pseudotumor of fibrous histiocytoma-type, pseudosarcomatous inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, inflammatory myofibrohistiocytic proliferations, and fibroxanthoma. Spencer221 coined the term pulmonary plasma cell/histiocytoma complex to emphasize the histologic heterogeneity that categorizes so-called inflammatory pseudotumors. The term inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor227 has been used to characterize a distinctive lesion in which proliferating myofibroblasts are the predominant cell type. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors occur over a broad age range from early childhood through adulthood.228,229 Most patients present with asymptomatic solitary pulmonary nodules. Symptomatic patients may have chest pain and dyspnea. In up to one third of patients, a syndrome of fever, weight loss, anemia, thrombocytosis, hypergammaglobulinemia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate is observed. Chest radiographs typically show a well-circumscribed mass that can range in size from 0.8 to 36 cm. Most measure 1 to 6 cm in size. Fifteen percent of cases have endobronchial involvement (Fig. 18–31).

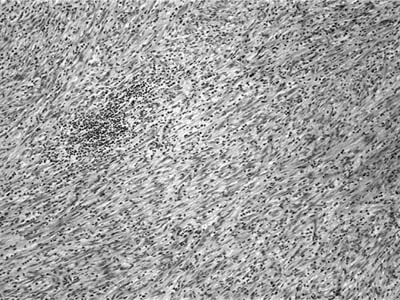

Grossly inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor is circumscribed and white-tan in color with a whorled fleshy or somewhat myxoid appearance. Hemorrhage, necrosis, and calcification are unusual. The lesions are usually solitary, but multiple nodules may be present. Three patterns have been described. The myxoid vascular pattern comprises loosely arranged plump or spindled myofibroblasts in an edematous background with abundant blood vessels and associated inflammatory cells (Fig. 18–32). This pattern resembles nodular fasciitis or granulation tissue. The compact fascicular pattern is characterized by a spindle cell proliferation with variable myxoid and collagenized regions. This variant has more significant inflammation (Fig. 18–33), aggregates of plasma cells, and may be quite cellular. This pattern resembles fibrous histiocytoma. The third pattern simulates a scar or a desmoid with ropey collagen, less cellularity, and minimal inflammation. The first two types often contain ganglion-like myofibroblasts with fascicular nuclei, eosinophilic nucleoli, and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm. The inflammatory cell component in all variants may include foamy histiocytes. Vessel invasion can be demonstrated in some cases and is of uncertain significance.230

FIGURE 18–31 Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with prominent endobronchial growth.

FIGURE 18–32 Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor composed of bland spindle cells set in a myxoid stroma.

Rare examples of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors undergo malignant transformation. Such tumors contain highly atypical polygonal cells with oval fascicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and an increased mitotic rate. Large ganglion-like cells and Reed-Sternberg–like cells may be prominent.

The immunohistochemical profile of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors is somewhat variable, but smooth muscle actin and muscle-specific actin are variably expressed in the spindle cell component. Desmin may be identified in some cases. Keratin reactivity is seen in about a third. Cytoplasmic reactivity for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) is detectable in about one half.231–237 This correlates well with the presence of ALK rearrangement detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH).

FIGURE 18–33 Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with a compact fascicular growth pattern and moderate chronic inflammation.

The prognosis for the pulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor is excellent, and most patients are cured with complete resection. Recurrences, however, do occur and are more frequent with multiple lesions at presentation and failure to resect completely. A combination of atypia, ganglion-like cells, p53 expression, and aneuploidy may help identify inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors with more aggressive potential.238

Current evidence suggests that inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor is a neoplasm, and in children and young adults clonal cytogenetic rearrangements that activate the ALK receptor, the tyrosine kinase gene on the short arm of chromosome 2, have been identified.231–237

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree