19

Lymphoproliferative Disorders

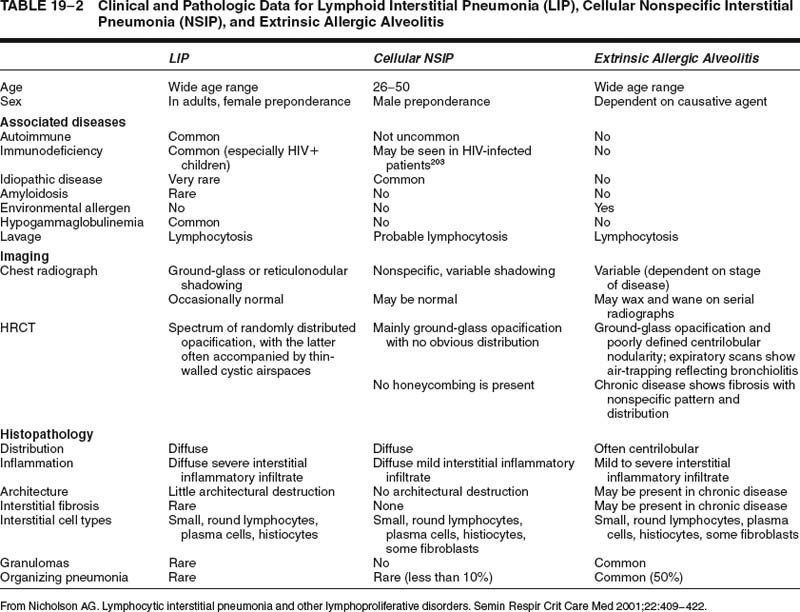

A variety of lymphoproliferative disorders, both reactive and neoplastic, can primarily or secondarily involve the lung (Table 19–1), and many of the historical arguments as to which are truly neoplastic and which are reactive have now been resolved through advances in immunohistochemistry and molecular biology. Furthermore, classification of the extranodal neoplasms has been refined in the recent World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors arising in hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, leading to greater uniformity in terminology. This chapter, therefore, describes the normal lymphoid constituents, those lymphoproliferative diseases considered to be reactive, primary and secondary neoplastic lymphoproliferative diseases involving the lung, and posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders.

Normal Pulmonary Lymphoid Tissue

Lymphoid tissue is a normal component of the lung, and may take the form of hilar or intraparenchymal lymph nodes, bronchial mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), lymphoreticular aggregates, and widely scattered interstitial lymphocytes.1–5 In understanding lymphoma development, the most important of these is bronchial MALT.1,2 Bronchial MALT is rare in normal fetuses and infants (~10%), although it is more frequently seen when there has been antigenic stimulation.6 Nevertheless, most people will have bronchial MALT within their lungs by adulthood as a result of a normal immune response, and foci tend to be most prominent at bifurcation points. Histologically, bronchial MALT typically comprises a germinal center, with a prominent marginal zone that is associated both with bronchial epithelium and lymphatics in the bronchovascular bundles. Intraepithelial lymphocytes may also be present,7 and both these lymphocytes and epithelial cells are likely involved with antigen transport and presentation in the context of the mucosal immune response.8–10 Nonencapsulated lymphoreticular aggregates are present in peripheral lung and tend to be distributed along the interlobular septa and visceral pleura.3 Small numbers of lymphocytes are also widely scattered throughout the interstitium.

Reactive/Hyperplastic Lymphoproliferative Disorders

Pulmonary lymphoid tissues are subject to the same range of disorders that occur in lymph nodes and at other extranodal sites. Morphologic manifestations of lymphoid hyperplasia in the lung depend on which lymphoid compartment is chiefly affected and whether the changes are patchy or diffuse.

Intrapulmonary Lymph Node

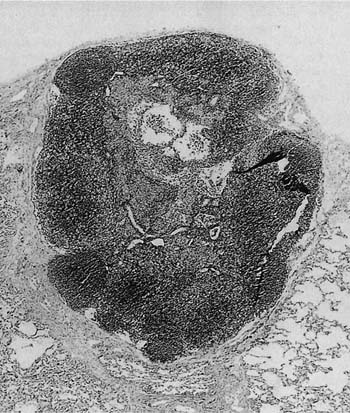

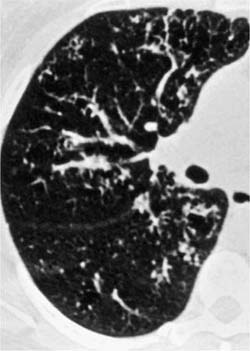

Pulmonary lymph nodes are a normal constituent of the lung, but can display the usual range of hyperplastic follicular changes (Fig. 19–1), as well as anthracosis and calcification.5 Pulmonary lymph nodes may also be involved by pathologic processes, especially in relation to occupational dust exposures. When hyperplastic, they are most commonly found in middle-aged men with a history of smoking. The nodes are probably not pathologic by definition, but are often biopsied in the context of the differential diagnosis of malignancy. Furthermore, the advent of high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) has resulted in more frequent recognition. Therefore surgery, cytologic sampling,11,12 or further investigations such as positron emission tomography may be necessary to aid in diagnosis, particularly in patients with malignant disease elsewhere.

Primary pulmonary/pleural neoplasms: extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) Diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma Lymphomatoid granulomatosis Hodgkin’s lymphoma Plasmacytoma Mast cell tumor Secondary involvement of the lung: Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas Intravascular lymphomatosis Leukemic infiltrations Malignant histiocytosis Myelofibrosis and extramedullary hematopoiesis Benign hyperplastic disorders: reactive pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia Follicular bronchiolitis/bronchitis Angiofollicular lymphoid hyperplasia Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLDs) Plasmacytic hyperplasia Polymorphic Monomorphic (classify according to lymphoma classification) Other types (rare, e.g., Hodgkin’s disease–like lesions, plasmacytoma-like lesion) |

Diffuse Pulmonary Lymphoid Hyperplasia

Diffuse pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia has been regarded as purely a synonym for lymphoid interstitial pneumonia,3 as well as a pattern of disease intermediate between follicular bronchiolitis and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia. However, as there is clearly clinical histologic overlap between follicular bronchiolitis and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, this author views it as a global term encompassing both follicular bronchiolitis and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia.

Lymphoid Interstitial Pneumonia

The term lymphoid interstitial pneumonia was introduced by Liebow and Carrington13 in 1969 to describe a diffuse interstitial lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate that was to be distinguished from usual interstitial pneumonia. Currently, it is part of the classification of both lymphoproliferative diseases and interstitial pneumonias.14 Patients with lymphoid interstitial pneumonia are more commonly female, with average presentation at ~50 years. They typically present with dyspnea, cough, and chest pain. Associated conditions include human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, especially in children,15–17 and systemic vascular disorders including Sjögren’s syndrome,18 Hashimoto’s disease,19 pernicious anemia,20 chronic active hepatitis,21 systemic lupus erythematosus,22 autoimmune hemolytic anemia,23,24 primary biliary cirrhosis,25 and myasthenia gravis.23 Patients more commonly show a polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia (~65%) than hypogammaglobulinemia (~20%).23,25–28 Chest x-rays show reticular, coarse reticulonodular or fine reticulonodular shadowing,23,25,26,29 and the presence of prominent linear patterns on the films may reflect peribronchiolar lymphoid infiltrates seen in biopsies.30 Studies using HRCT scanning have also described formation of cystic dilated airspaces, both in lymphoid interstitial pneumonia with amyloidosis31 and in isolation.32

FIGURE 19–1 A low-power magnification shows an intrapulmonary lymph node with mild follicular hyperplasia lying within the peripheral alveolar parenchyma. The nodal architecture is normal.

The cause of lymphoid interstitial pneumonia is unknown and most likely multifactorial. There is evidence that Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection may have a role in pathogenesis in some patients,33–35 and clones of lymphoid cells with high sequence homology to auto-reactive lymphocytes have been found in some cases, supporting autoimmunity as a second pathogenetic mechanism.36 Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia is also associated with congenital immunodeficiency, again suggesting other pathways of lymphocyte dysregulation.37,38 High levels of chemokines such as interleukin-18 (IL-18) are found in cases associated with HIV infection and may be in part responsible for recruitment of inflammatory cells into the interstitium.39

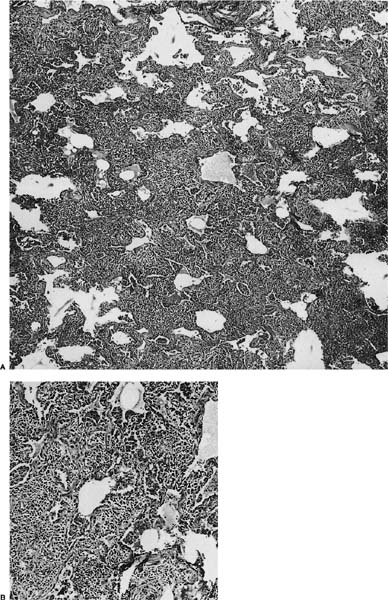

FIGURE 19–2 (A) A case of lymphoid interstitial pneumonia from an HIV-infected individual shows interstitium markedly expanded by a dense lymphoid infiltrate but with comparative little architectural loss and filling of the alveolar spaces. (B) At high power, the infiltrate comprises small round lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes.

Histologically, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia is characterized by a heavy interstitial lymphoid infiltrate with minor peribronchial involvement (Fig. 19–2). Granuloma formation is sometimes noted.25,26,29 Immunohistochemistry using CD20 shows that B cells are mainly limited to germinal centers. The interstitial lymphocytes are predominantly T cells, plasma cells, and histiocytes, mixed with only scattered small B lymphocytes. Amplification of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene using the polymerase chain reaction shows a polyclonal pattern.29

The clinical course is extremely variable. Some patients have complete and lasting remission; others remain stable for months or years before progressing to pulmonary fibrosis, honeycombing,40 and cor pulmonale; and some die within months.25,26,29,40 Treatment is usually with corticosteroids, with or without cytotoxic therapy. In relation to etiology, some patients with symptomatic HIV-related lymphoid interstitial pneumonia have improved following highly active antiretroviral therapy.41

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia is a rare disorder. Nonspecific lymphoid infiltrates in the vicinity of localized lung diseases, such as tumors or chronic infective lesions, are much more common, highlighting the importance of knowing both the clinical data and the distribution of disease before making the diagnosis. A diffuse predominantly lymphoid infiltrate can also be present in other diffuse lung diseases, such as extrinsic allergic alveolitis42 and cellular variants of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP),14 from which lymphoid interstitial pneumonia requires differentiation. Usually, hypersensitivity pneumonia will be slightly bronchocentric in distribution, whereas cellular NSIP is characterized by much milder interstitial expansion. Differentiation of these conditions on histology alone may not be possible with small biopsy specimens. The distinction is facilitated in some cases by correlation with clinical data, especially HRCT findings (Tables 19–2 and 19–3). Distinction of lymphoid interstitial pneumonia from marginal zone lymphomas of MALT origin is covered in a later section.

Follicular Bronchitis/Bronchiolitis

Follicular bronchitis/bronchiolitis is a predominantly peri-bronchial lymphocytic infiltrate with abundant germinal centers, often associated with various systemic disorders. Patients commonly present in middle age and often have underlying connective tissue diseases, a subgroup in which women predominate. Immune deficiency syndromes and ill-defined “allergic” backgrounds occur in other patients.43 Symptoms include progressive shortness of breath, fever, cough, and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections.43 Chest x-ray findings are similar to those seen in lymphoid interstitial pneumonia,23,25,26,29,43,44 but the HRCT scan findings are better defined with bilateral centrilobular and peribronchial nodules and less frequently ground-glass opacification (Fig. 19–3).45 Most patients show a good response to steroid therapy.

As discussed in relation to diffuse pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia, follicular bronchiolitis and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia represent overlapping histologic patterns, both patterns representing a response of the pulmonary immune system to a variety of unknown factors,23,25,43 and lymphoid hyperplasia is the common pathogenetic mechanism.3 However, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia alone is reported to carry a low risk of lymphomatous transformation.46,47 and so some differences in clinical data are apparent.

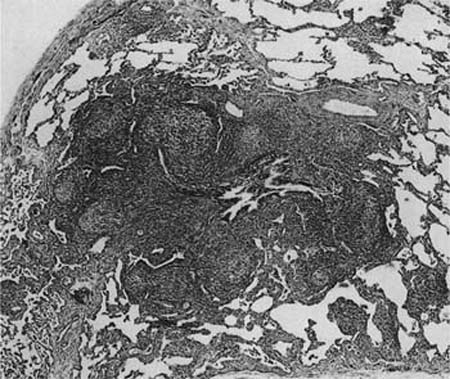

Histologically, follicular bronchiolitis is characterized by prominent peribronchial and peribronchiolar lymphoid follicles with a minor interstitial inflammatory component (Fig. 19–4). Hyperplastic follicles may also been seen in the interlobular septa and the visceral pleura. Compression of the airway lumina not infrequently leads to obstruction and a resultant intraluminal acute inflammatory cell infiltrate, plus endogenous pneumonia in some cases. The differential diagnosis for follicular bronchiolitis is limited. It should be distinguished from follicular bronchiectasis, a term used when prominent follicular hyperplasia is accompanied by marked airway dilatation, as seen in patients with conditions such as cystic fibrosis.43 Hypersensitivity pneumonia may show prominent peribronchial lymphoid follicles, but there are usually granulomas and there is nearly always a significant interstitial inflammatory infiltrate. Follicles may also be prominent in middle lobe syndrome.48 Secondary involvement by lymphoma may also be focally bronchiolar but will usually also show a dense infiltrate along the distribution of the pulmonary lymphatics.

FIGURE 19–3 Partial section of a high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan from a case of follicular bronchiolitis that shows focal bronchocentric nodularity throughout the lung parenchyma. (Courtesy of D. M. Hansell, Royal Brompton Hospital.)

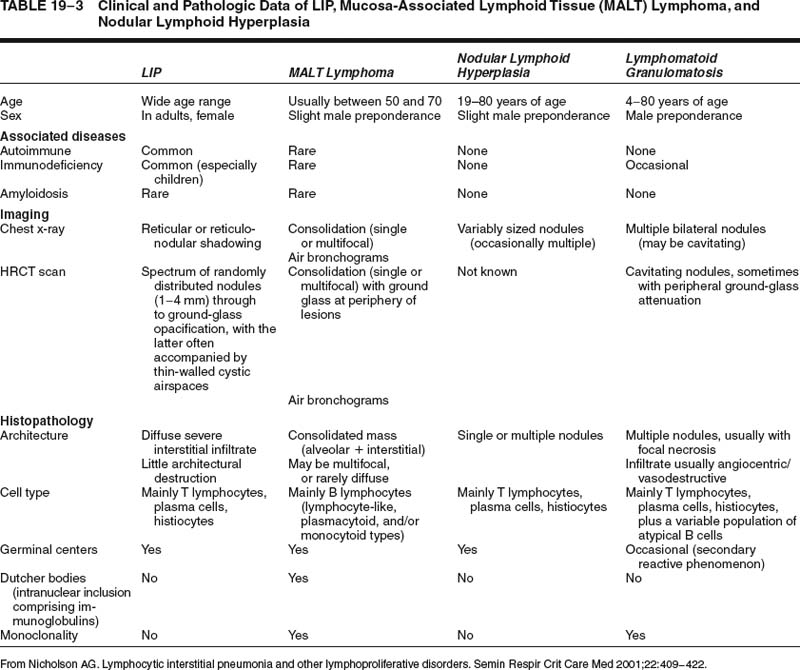

Nodular Lymphoid Hyperplasia (“Pseudolymphoma”)

In 1962 Saltzstein49 studied 102 patients with primary pulmonary lymphoproliferative disease and, finding a strikingly low incidence of dissemination, he concluded that many represented a form of chronic inflammation. For these, he introduced the term pseudolymphoma regarding them as analogous to similar lesions in the salivary glands, orbit and elsewhere. This was based on specific histologic features, namely a lack of nodal involvement, and localization to the lung,49 but in the last two decades immunohistochemistry and molecular studies have shown evidence of monoclonality within most pseudolymphomas,50–53 and the majority of cases are now believed to have been marginal zone B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas of MALT origin.51–53 However, a minority of such cases still lack evidence of clonality and the term nodular lymphoid hyperplasia is now preferred to pseudolymphoma, as its reactive nature is implicit within the name.54 Patients have a wide age range and are usually asymptomatic, though fever and a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are seen in a few cases. In the only series to date, there were eight women and six men, ranging from 19 to 80 years (median, 65 years) in age.54 Most cases are incidental single masses found on routine chest x-rays, which are typically consolidated and cream-colored on macroscopic examination.

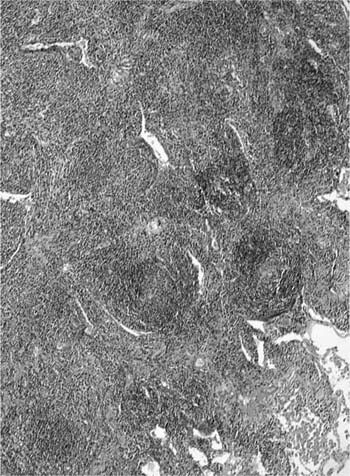

The lesions comprise abundant reactive germinal centers, intense interfollicular polyclonal plasmacytosis, and a variable degree of interfollicular fibrosis (Fig. 19–5). Neither genetic mutations nor evidence of rearrangement of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene are found. Recurrence has not been reported after surgical excision, and in patients with multifocal disease, steroids and cytotoxic drugs (cyclophosphamide and azathioprine) may be beneficial. The main differential diagnosis is marginal zone lymphoma of MALT origin and, as histologic features may overlap, exclusion of clonality through immunohistochemistry and molecular analysis is generally required (Table 19–3).

Angiofollicular Lymph Node Hyperplasia (Castleman’s Disease)

Castleman’s disease typically affects mediastinal lymph nodes but has been reported in the pleura,55 chest wall,56 and rarely within the lung.57,58 Two histologic patterns are described, namely the hyaline-vascular variant and the plasma cell variant. Most pulmonary cases described in the lung are of the hyaline-vascular type, with lesions usually being localized and generally asymptomatic. The plasma cell variant may have an aggressive course and be associated with lymphoid interstitial pneumonia.59 Multicentric Castleman’s disease associated with HIV infection has been shown to have a high prevalence of pulmonary symptoms,60 although the relationship between Castleman’s-like features and HIV infection remains subject to debate.

FIGURE 19–4 A case of follicular bronchiolitis shows prominent aggregation of germinal centers with follicular hyperplasia, which causes partial compression of the bronchiolar lumen.

Primary Pulmonary Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas

Primary pulmonary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was originally defined as a lymphoma that presented primarily in the lungs, with or without hilar node involvement but without clinical evidence of disease elsewhere.49 Series of pulmonary lymphomas in the 1970s and 1980s were categorized according to lymph node classifications,61–64 but later series have classified most examples under the heading of MALT lymphomas.51–53,65–67 Originally, MALT lymphomas were divided into low-grade and high-grade subtypes. Those tumors with low-grade features have the characteristic histology of MALT lymphomas arising at other sites, and, although the rarer tumors with high-grade usually lack these distinctive morphologic features, a significant number likely arise from MALT, as low-grade areas are described in some high-grade tumors.52,53,68,69 Currently, the WHO classification recommends the term extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) for those with low-grade features and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma for those with high-grade features, and these two patterns are therefore discussed accordingly.

Extranodal Marginal Zone B-Cell Lymphoma of Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (MALT Lymphoma)

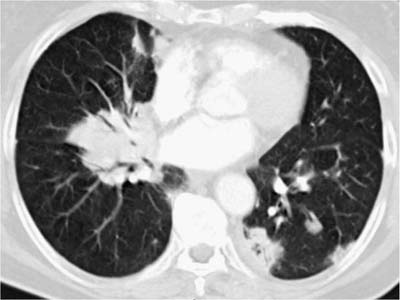

These tumors account for less than 0.5% of all primary lung neoplasms and a similarly low proportion of all lymphomas. Patients’ ages generally range from 50 to 70, with a slight male preponderance. The most common presentation is an asymptomatic mass on routine chest x-ray, with symptoms, when present, including cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and hemoptysis. Previous or synchronous MALT lymphomas at other extranodal sites are not infrequent, and there may be a monoclonal gammopathy. Some patients have systemic (“B”) symptoms. Imaging shows variable patterns, with unilateral or bilateral disease, isolated or multiple opacities, diffuse infiltration, reticulonodular shadowing, and pleural effusions all being described.70 Air bronchograms are a characteristic feature. HRCT scans typically show consolidative multiple or solitary masses, with associated air bronchograms, airway dilatation, positive angiogram signs, and haloes of ground-glass shadowing at lesion margins (Fig. 19–6).70 Diagnosis can be made via sputa, bronchial brushings, washings, lavages, and aspiration biopsy specimens from the respiratory tract, as well as bronchoscopic or transbronchial biopsies,53,71–77 although ancillary investigation such as immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, and molecular analysis are not infrequently required in these instances.78,79 In terms of cytologic specimens, samples comprise cellular and dyscohesive populations of small lymphoid cells (Fig. 19–7). Correlation with HRCT data may help in reducing the need for more invasive investigations.

FIGURE 19–5 A pulmonary nodule from a case of nodular lymphoid hyperplasia comprises a localized dense lymphoid aggregate, made up of hyperplastic germinal centers interspersed by a mixed infiltrate of plasma cells and small, round lymphocytes. The features are not dissimilar to marginal zone lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) origin, but there is no evidence of clonality.

In terms of etiology, it is known that gastric lymphomas arise from MALT acquired as a result of Helicobacter pylori infection80 and that antigen stimulation plays a role in clonal expansion.81 Data are not so straightforward in the lung as the bronchial MALT (from which pulmonary lymphomas are thought to arise) develop in response to various less well defined antigenic stimuli.6,82–84 Carcinogenesis, therefore, is likely to be multistep and mutlifactorial, in that smoking causes an increased incidence of bronchial MALT,83 and pulmonary lymphomas are described in patients with autoimmune disorders85,86 or coexistent tuberculosis,87 and in patients with hepatitis C.88 However, the latter coexistent infections are very rare in association with this type of lymphoma, and, given their relative frequency in the general population, their presence may equally be coincidental. It may also be that prolonged turnover rates of B cells contributes to lymphomagenesis, with immunosuppressive therapy being a possible additional factor.89,90 Cytogenetic studies have shown both t(1;14) and t(11;18) (q21;q21) translocations, though the most common abnormality has been trisomy of chromosome 3. How these abnormalities relate to lymphomagenesis remains obscure, but the high incidence of trisomy 3 in both the extranodal and nodal marginal zone lymphomas supports the view that they are distinct from other types of nonHodgkin’s lymphomas.91–93 Bcl-10 expression and mutation of its gene may also contribute to carcinogenesis.94

FIGURE 19–6 An HRCT scan from a case of marginal zone lymphoma of MALT origin shows bilateral consolidation with air bronchograms and ground-glass shadowing at the periphery of the masses. (Courtesy of D. M. Hansell, Royal Brompton Hospital.)

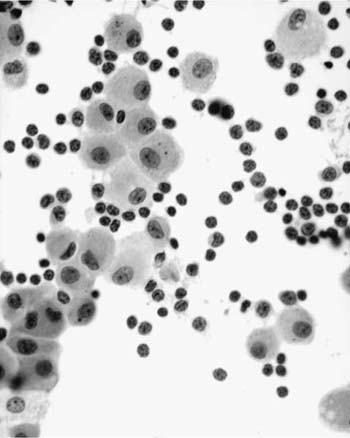

FIGURE 19–7 Increased numbers of small, round lymphocytes are seen in a bronchoalveolar lavage from a patient being investigated for right middle lobe consolidation. An excision biopsy confirmed marginal zone lymphoma of MALT origin.

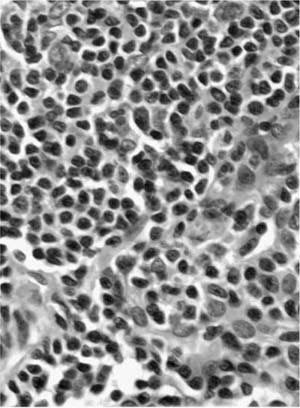

Macroscopically, areas of involvement typically show a cream-colored consolidated mass, not dissimilar in texture to the cut surface of a lymph node involved by lymphoma (Fig. 19–8). Microscopically, tumors comprise a mixture of small lymphocytes that may be centrocyte-like, lymphocyte-like, or monocytoid in morphology, all thought to be variations of the same neoplastic cell (Fig. 19–9).68 Infiltration of bronchial or bronchiolar epithelium, so-called lymphoepithelial lesions, are characteristic (Fig. 19–10). Neoplastic cells typically track along bronchovascular bundles and interlobular septa at the periphery of lesions, with the alveolar parenchyma being destroyed toward the center. However, bronchovascular bundles often remain, correlating with the presence of air bronchograms on HRCT. Sclerosis may also be a feature. The pleura may also be involved. Germinal centers are frequently seen, highlighted by antibodies that recognize follicular dendritic cells (CD21), and these often appear abnormal in architecture due to partial destruction. Giant lamellar bodies, eosinophilic whorled structures occurring singly or in clusters within alveolar ducts and spaces, are seen in ~20% of cases.95 Vascular infiltration, pleural involvement, and granuloma formation are not uncommon, but have no prognostic significance. Necrosis is very rare. Tumors may also be seen in association with amyloidosis.69,96 The neoplastic cells are of B-cell phenotype, and may be identified by CD20 or CD79a staining. Variable numbers of reactive T cells are also present. Light chain restriction is observed in 30 to 70% of cases. Amplification of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene with the polymerase chain reaction shows monoclonality in ~60% of cases.53,67 The features of nodal involvement are those of nodal marginal zone B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas.97,98

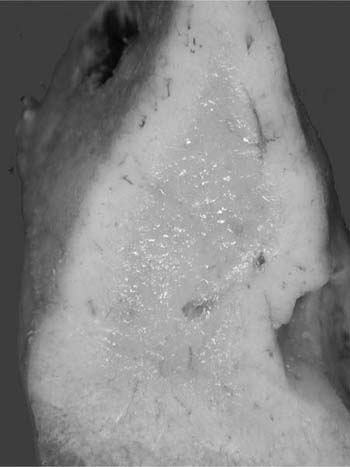

FIGURE 19–8 A resected right middle lobe is partially replaced by cream-colored consolidation.

In terms of treatment, tumors are staged as either Ie (unilateral or bilateral pulmonary involvement) or IIe (Ie plus hilar/mediastinal involvement), although it is almost impossible to relate stage to therapy as treatment has varied over the years, cases are sporadic, and the diagnosis has often been made after potentially curative resection. However, in patients with complete resections, surgery has resulted in prolonged remission.99 Chemotherapy is governed by principles that apply to more advanced small lymphocytic nodal lymphomas. Overall, 5-year survival is 84 to 94%.52,53,66 When metastases occur, there is preferential spread to other mucosal sites rather than to lymph nodes.53,65

FIGURE 19–9 A case of marginal zone lymphoma of MALT origin shows a dense lymphoid infiltrate that is lymphocyte-like in type. A lymphoepithelial lesion is noted at the top of the picture.

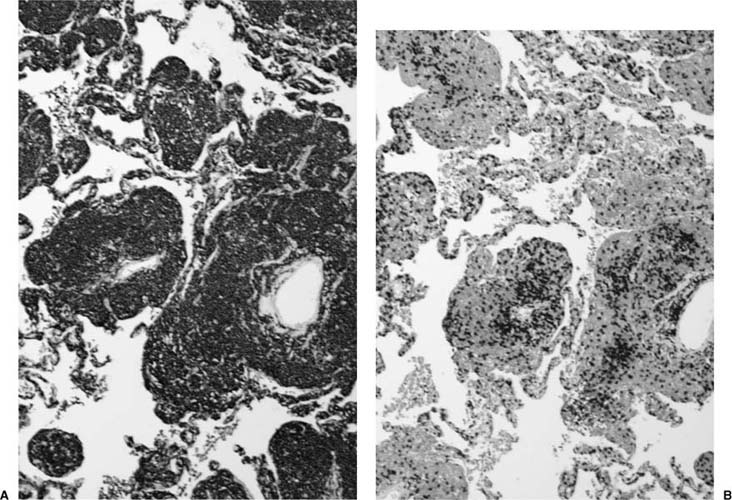

From the clinical and imaging aspects, the differential diagnosis not infrequently includes bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma and organizing pneumonia. In these instances a cytologic specimen or endoscopic biopsy with a dense lymphocytic infiltrate and the appropriate immunophenotype may be sufficient for diagnosis. In terms of morphology, the main differential diagnosis is reactive pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia, specifically lymphoid interstitial pneumonia. Problems are most commonly encountered when architectural features of lymphoma are lacking. However, lymphomas tend to infiltrate and destroy the alveolar architecture to a greater degree and also show greater expansion of alveolar septa by the lymphoid infiltrate. In addition, lymphoepithelial lesions are rarer in lymphoid interstitial pneumonia. Furthermore, neoplastic B cells infiltrate the alveolar interstitium widely in lymphomas, whereas the pattern of a reactive infiltrate is of aggregated B cells that are usually peribronchial or septal in distribution (Fig. 19–11). Further evidence of lymphoma can be found by identifying light chain restriction or monoclonality using molecular studies.53,100 Distinction from secondary involvement by other types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is via clinical data. In addition, marginal zone lymphomas of MALT origin are negative for CD5 and CD10. Lymphocyte-rich (WHO type B1) variants of thymoma involving the lung may also rarely be mistaken for lymphoma,101 although staining for cytokeratins, CD3, and CD1a distinguishes between thymoma and lymphoma.

FIGURE 19–10 Lymphoepithelial lesions are frequently seen in a marginal zone lymphoma of MALT origin (cytokeratin stain).

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

Diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas account for ~20% of primary pulmonary lymphomas. Patients’ ages are similar to those with marginal zone non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas of MALT origin, but presentation is nearly always symptomatic with cough, hemoptysis, and dyspnea. Again, patients may complain of systemic (“B”) symptoms. Imaging shows solid, often multiple masses. Their etiology is less well defined than for marginal zone non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas of MALT origin, but some likely represent high-grade transformation from these tumors (Fig. 19–12),102 probably through further mutation. One study showed that the majority of primary pulmonary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma arising in the context of fibrosing alveolitis and collagen vascular disease were of this type.86 Grossly, areas of pulmonary involvement are typically solid, firm, and cream-colored masses, but paler and softer areas that correlate with necrosis may also be seen (Fig. 19–13).

FIGURE 19–11 (A) A CD20 stain highlights the B-cell phenotype of the tumor cells in a marginal zone lymphoma of MALT origin. (B) CD3 staining shows a variable number of T cells in the background.

Microscopically, in contrast to marginal zone lymphomas of MALT origin, diffuse large B-cell nonHodgkin’s grade lymphomas are much more diffuse, with sheets of blastic lymphoid cells infiltrating and destroying the lung parenchyma (Fig. 19–14). Vascular infiltration and pleural involvement are still commonly seen, but lymphoepithelial lesions are rarer and necrosis is common. The neoplastic cells are of B-cell phenotype, again with a reactive T-cell population in the background. Monoclonality via amplification of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene with the polymerase chain reaction is infrequently demonstrated.53 Staging as either Ie (unilateral or bilateral pulmonary involvement) or IIe (Ie plus hilar/mediastinal involvement) is again recommended. Patients may inadvertently undergo resection for localized disease in the process of diagnosis, but most patients require combination chemotherapy from the outset, often with high response rates.103,104 Overall, 5-year survival ranges from 0 to 60%.52,53,66

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree