Tuberculous and Fungal Infections of the Pleura

Carlos A. Olivares-Torres

Jose Morales-Gomez

Graciano Castillo-Ortega

Mycobacterial and fungal infections of the pleural space, especially tuberculosis, are a leading cause of worldwide morbidity and mortality, and tuberculosis (TB) is also on the rise in the western world.70 Pleural TB is considered a form of extrapulmonary TB and is most often a secondary phenomenon of primary infection. It requires pleural biopsy for diagnostic purposes. Approximately 5% of patients with TB will develop a pleural effusion. Empyema caused by reactivation of TB rarely occurs in patients who have received adequate medical treatment, but it represents a real challenge to the thoracic surgeon. In a series of 380 empyema patients reported by Weissberg and Refaely,67 no case of fungal infection was mentioned. Fungal empyema typically occurs in residual pleural spaces after previous resection or radiation therapy; these cases are particularly difficult, marked by chronic illness and consumption. With the resurgence of HIV infection and the interaction with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, these cases are often complex and hard to treat.

There are no general guidelines for the treatment of any empyema caused by tuberculous and/or fungal empyema. A first step is to eliminate gross contamination, either with tube thoracostomy or open-window thoracostomy. Usually drainage of the pleural space plus treatment of the M. tuberculosis or the fungal infection suffices, and there is no need for complete and definitive obliteration of the space (which must be achieved to prevent further relapse of the infection). The procedure of choice should be an open pleural window, either an Eloesser flap or a modification of this technique. A decortication should not be done in a patient who has active TB. Open-window thoracostomy may be a lifesaving procedure in acutely ill patients; permanent loss of function must be expected when the lung remains trapped below an armor of fibrotic scar tissue. The common feature of chronic mycobacterial and fungal infections is that often the underlying lung cannot be reexpanded to fill the pleural space, either because of previous partial resection or diffuse fibrosis. In the latter case, the goal of treatment may be achieved either with thoracoplasty or various pedicled flaps developed from the chest wall muscles as well as use of the greater omentum.

Pleural Tuberculosis

Tuberculous infection of the pleura is a disease of the past. However, there is an upswing in incidence in third world and developing countries because it is often associated with HIV infection.23 Most of the principles of treatment that were defined during the 1950s and 1960s are still valuable today.20 Langston and colleagues36 stated that TB of the pleura may manifest itself clinically and pathologically in a variety of ways. It varies from a thin idiopathic effusion that may yield acid-fast bacilli with difficulty, if at all, to a thick purulent exudate that has positive results on direct smears. All gradations and combinations of extent as well as character of pleural involvement or bacteriologic content are seen, as noted by Langston and associates.36 Nevertheless, for clarification, we subdivide the subsequent discussion into four groups defined by the history of disease:

During primary TB, pleural effusions appear in approximately 5% (4% United States, 23% Spain) of patients.56 The fluid is usually serofibrinous, and this condition should be called tuberculous pleuritis.

During reactivation of TB, pleural infection turns into a true empyema, characterized by an opaque, purulent effusion. Such tuberculous empyemas may be either pure or mixed. In the case of bronchopleural fistula, other microorganisms can infect the pleura together with M. tuberculosis.

The particular setting of late complications secondary to collapse therapy for TB, which is infrequently encountered today, presents varying complex problems.

Tuberculous Pleuritis

According to Jereb and colleagues,30 the pleural space is the second most common site of extrapulmonary TB, the first being the lymphatic system. Pleural infection, as noted by Weir and Thornton,66 is supposed to originate from subpleural

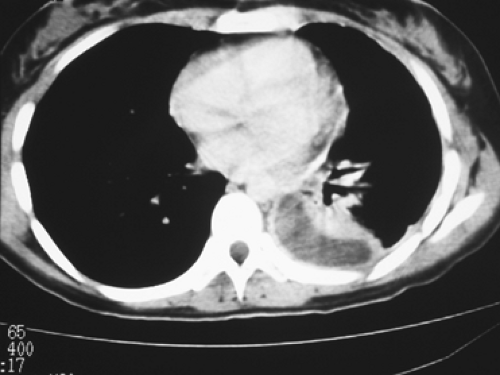

pulmonary lesions, with the rupture of these subpleural caseous foci in the lung into the pleural space. The clinical presentation is well known.20 General signs include low-grade fever, weakness, weight loss, and night sweats. Respiratory symptoms are nonproductive cough, pleuritic chest pain, and dyspnea correlated with the extent of effusion, which arises from increased capillary permeability and the impairment of lymphatic clearance of proteins and fluid from the pleural space. Tb pleuritis often manifests itself with an acute onset of pain and nonproductive cough.30 Chest radiography shows a pleural effusion (Fig. 63-1); computed tomography (CT) can also be helpful in assessing pleural thickening and fluid buildup (Fig. 63-2). Concomitant parenchymal disease is observed in approximately one-third of cases. At the early stage of disease, the tuberculin skin test result is positive in 75% of patients, but—according to Berger and Mejia4—it should be positive in virtually all patients by 2 months with the exception of patients with AIDS.

pulmonary lesions, with the rupture of these subpleural caseous foci in the lung into the pleural space. The clinical presentation is well known.20 General signs include low-grade fever, weakness, weight loss, and night sweats. Respiratory symptoms are nonproductive cough, pleuritic chest pain, and dyspnea correlated with the extent of effusion, which arises from increased capillary permeability and the impairment of lymphatic clearance of proteins and fluid from the pleural space. Tb pleuritis often manifests itself with an acute onset of pain and nonproductive cough.30 Chest radiography shows a pleural effusion (Fig. 63-1); computed tomography (CT) can also be helpful in assessing pleural thickening and fluid buildup (Fig. 63-2). Concomitant parenchymal disease is observed in approximately one-third of cases. At the early stage of disease, the tuberculin skin test result is positive in 75% of patients, but—according to Berger and Mejia4—it should be positive in virtually all patients by 2 months with the exception of patients with AIDS.

Figure 63-1. 23-year-old female with a pleural effusion and thickening of the pleura that required biopsy for diagnosis. |

Figure 63-2. CT scan showing pleural thickening with fluid trapped in the pleural space. The patient underwent a VATS procedure for drainage and biopsy of her disease. |

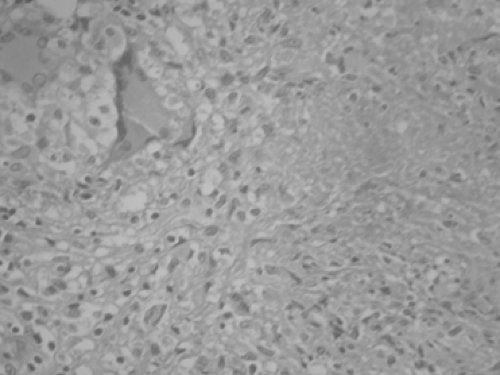

Positive diagnosis relies on direct sampling of the pleural fluid and on pleural biopsies with either a closed technique or a video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) procedure. Gross analysis of pleural fluid reveals an exudative fluid with a protein level in excess of 40 g/L and a white cell count of 1 to 6 g/L, with predominant lymphocytes. Absence of desquamated mesothelial cells suggests TB, as reported by Weir and Thornton.66 Determination of glucose level is not really useful. Cultures take 3 to 6 weeks, and the results are inconsistently positive. Only 30% of cultures became positive in Berger and Mejia’s experience.4 In the study of Caminero and colleagues,5 determination of IgG antibody levels to mycobacterial antigen 60 with a cutoff value of 150 U/mL had a sensitivity of 50% and a specificity of 100%. The sophisticated determination of adenosine deaminase (ADA) has been found by Berenguer and associates3 to have a poor sensitivity and specificity. A meta-analysis of ADA analysis has been published.21 Falk16 noted that cultures from sputum or gastric content are expected to be negative unless there is radiologic evidence for parenchymal disease. Therefore the most reliable investigation is pleural biopsy. Bates2 and Berger and Mejia4 reported that pleural biopsy with the Abrams needle or a similar device yields a positive result in 60% to 80% of patients. According to Yim,71 VATS achieves a high level of specificity because multiple biopsies increase the diagnostic threshold. Given the remarkably low operative risk, it seems reasonable to proceed with thoracoscopy when direct examination of bacteriologic samples is negative, rather than waiting several weeks for the result of cultures. Histologic evidence of caseating epithelioid granulomas is indicative of TB (Fig. 63-3). Levine and colleagues39 recommended that immediate antituberculous therapy be commenced, although only identification of acid-fast bacilli is completely diagnostic.

In summary, the diagnostic criteria defined by Langston and associates36 are still valuable today. Tuberculous pleuritis is diagnosed with pleural fluid positive for M. tuberculosis, and pleural disease is consistent with tuberculous granuloma on histologic study of biopsied or resected tissue.

The natural history of tuberculous pleuritis is usually benign, with spontaneous resorption even if untreated. Usual

management includes antituberculous treatment and close observation. Most often, patients respond favorably. However, depending on the individual patient’s immunologic status, excessive production of exudative material may start a diffuse thickening of the visceral pleura, leading to an entrapment of the lung, regardless of whether adequate antituberculous treatment is used. Such residual pleural disease is a threat for reactivation of TB or further development of a bronchopleural fistula; therefore pleural drainage or decortication should be considered (Table 63-1).

management includes antituberculous treatment and close observation. Most often, patients respond favorably. However, depending on the individual patient’s immunologic status, excessive production of exudative material may start a diffuse thickening of the visceral pleura, leading to an entrapment of the lung, regardless of whether adequate antituberculous treatment is used. Such residual pleural disease is a threat for reactivation of TB or further development of a bronchopleural fistula; therefore pleural drainage or decortication should be considered (Table 63-1).

Figure 63-3. Pleural biopsy obtained via a VATS procedure. A hematoxylin and eosin stain shows multiple granulomata in a 23-year-old female. |

Table 63-1 Treatment Plan for Chronic Mycobacterial or Fungal Empyema | |

|---|---|

|

Indications for decortication rely on careful examination of medical imaging. Previously, the indication for decortication was confirmed with lateral chest radiography. It was assumed that pleural disease seen on a posteroanterior projection but not visible on lateral films was diffuse around the pleural sac, and that a minor thickness of the pleural peel occurred. Such cases were expected to clear progressively. On the other hand, an effusion visible on both anteroposterior and lateral views corresponded to a large posterior pocket with a relatively thick pleural peel by virtue of dependent accumulation. Such encapsulated pleural processes are not likely to resolve completely unless they are small at the onset. In cases with a thick pleural peel, Langston and colleagues36 recommend decortication. CT has confirmed this approach for assessment of the underlying lung.

Determination of the appropriate timing of surgical intervention was clearly defined in 1967,26 and no obvious reason exists to change these criteria: (a) decortication is indicated when thoracentesis fails to yield fluid or fails to alter radiographic appearance; (b) the extent of pleural involvement should be equivalent to one-third or one-fourth of the hemithorax and cast a clearly discernible shadow in the posterior basal gutter; and (c) decortication should be made as early as is consistent with good judgment (i.e., after 2 to 4 months of drug therapy).

A thoracoscopic (VATS) procedure should also be considered even with pleural thickening. It allows multiple biopsies and drainage in the costovertebral angles with minimal invasion. It should be noted that the same caveats apply as with an open procedure: complete lung expansion, minimal trauma to the lung, and no residual cavities. Yim71 and others have reported that isolated cases have been managed successfully by VATS techniques. The diagnostic yield seems to be 100% on histology and 76% positive on culture.

Tuberculous Empyema

Pleural reactivation of TB has been a threat in patients who did not receive major antituberculous drug therapy. Moreover, chronic empyema is frequently complicated by bronchopleural fistula, leading to a mixed empyema or complicated tuberculous pleural effusion, characterized by contamination with both M. tuberculosis and common pyogens. Chronic empyema following TB adequately treated with antituberculous antibiotics is seldom associated with reactivation of TB in the pleural space. None of the 22 patients treated by Garcia-Yuste and coworkers19 had any evidence of ongoing mycobacterial infection.

Diagnosis is easy in patients with known sequelae of TB. Low-grade fever, constitutional complaints, and increasing dyspnea with or without chest pain are the major symptoms. Abundant sputum suggests presence of a bronchopleural fistula. On chest radiography, the obvious finding is an increase in the extent of the pleural involvement. The appearance of an air fluid level heralds a bronchopleural fistula. Thoracentesis yields purulent fluid, which should be sent routinely for both bacterial and fungal cultures. Thoracentesis may be difficult in the patient with a calcified pleura.

As soon as empyema is confirmed, an adequate drainage procedure should be instituted. Our preference is open pleural window, whereas others prefer immediate thoracostomy. In patients with documented reactivation of TB, the classic principle—to convert sputum cultures with medical treatment before resection—should still be applied, as recommended by Treasure and Seaworth.64 The next step is to plan for definitive treatment, which implies major thoracic surgery with often complicated outcomes (Table 63-1).

The first question is to determine whether the underlying lung is reexpandable. Ideally, one would prefer the most conservative approach, which consists of reexpanding the lung with decortication. The CT scan is most helpful in the evaluation of the entrapped lung. Areas with cavitations or large cystic bronchiectases obviously will not reexpand. Conversely, Mouroux and associates,49 as well as Treasure and Seaworth,64 have found that a patent bronchopleural fistula does not preclude decortication.

The second question is to determine whether parenchymal resection is required. Tuberculous lungs are relatively stiff, and loss of volume leads to residual pleural space, a factor for persistent empyema postoperatively. Therefore combined

parenchymal resections should adhere strictly to the classic indications as reported by Pomerantz54 and Mouroux49 and their colleagues as well as by Treasure and Seaworth64: multiple drug-resistant disease, threat of hemoptysis, and infectious complications such as bronchiectasis or aspergilloma. The current criteria for drug resistance are clinical or radiologic evidence of progressive disease and persistent mycobacteria on sputum examination after 3 months of a four-drug treatment. At an earlier stage, bacillar casts may be visible on direct examination of smears but fail to grow in culture. When the remaining lung is extensively destroyed, extrapleural pneumonectomy is to be considered as a last resort. We would, however, raise some admonitions against this difficult and potentially dangerous procedure. Publications by Halezeroglu24 and Conlan9 and their associates as well as by Odell and Henderson52 conclude that both previous TB and coexistent empyema are significant risk factors for pneumonectomy morbidity and mortality.

parenchymal resections should adhere strictly to the classic indications as reported by Pomerantz54 and Mouroux49 and their colleagues as well as by Treasure and Seaworth64: multiple drug-resistant disease, threat of hemoptysis, and infectious complications such as bronchiectasis or aspergilloma. The current criteria for drug resistance are clinical or radiologic evidence of progressive disease and persistent mycobacteria on sputum examination after 3 months of a four-drug treatment. At an earlier stage, bacillar casts may be visible on direct examination of smears but fail to grow in culture. When the remaining lung is extensively destroyed, extrapleural pneumonectomy is to be considered as a last resort. We would, however, raise some admonitions against this difficult and potentially dangerous procedure. Publications by Halezeroglu24 and Conlan9 and their associates as well as by Odell and Henderson52 conclude that both previous TB and coexistent empyema are significant risk factors for pneumonectomy morbidity and mortality.

The postoperative course after decortication with or without additional parenchymal resection may be complicated mainly by pleural space disease. Prolonged air leaks ultimately seal with long-term drainage provided that the lung is completely expanded. Persistent pleural spaces after decortication may be managed either with muscle flaps, plombage, thoracoplasty, or open pleural window. Thoracoplasty has an unwarranted bad name and should be considered in patients with marked malnutrition; a four-rib thoracoplasty with a stable and retracted mediastinum may be expeditiously carried out, as noted by Hopkins and associates,26 compared with the preparation and transfer of two or three muscle flaps. Rather than performing an immediate thoracoplasty as in former years, we prefer to test the expansion potential of the remaining lung and to proceed with second-stage thoracoplasty only when it proves to be necessary. Creating an open-window thoracostomy initially is an important decision, because decortication cannot be performed in a second stage. However, Garcia-Yuste and colleagues19 suggest that two-stage management with thoracostomy and subsequent muscle plombage of the cleaned residual space is a reasonable alternative in cases unsuitable for decortication. Poor general health status and extensive calcifications precluding decortication are indications for this type of management (Fig. 63-4). In the case of a largely destroyed but asymptomatic lung, two-stage myoplasty may help avoid the temptation to proceed with extrapleural pneumonectomy. Regardless of the type of surgical management, adjuvant antituberculous treatment is mandatory in cases of documented reactivation of TB.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree