Truncus Arteriosus

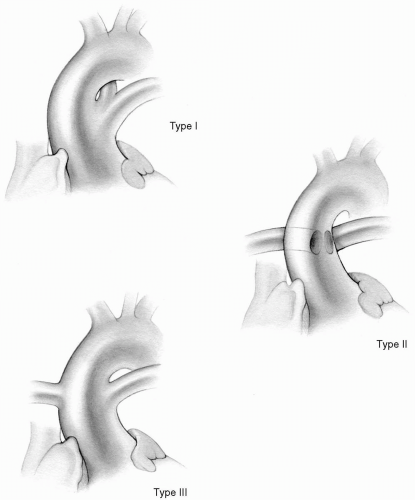

Persistent truncus arteriosus is characterized by the emergence of a single common arterial trunk from the heart overriding the interventricular septum. The main pulmonary artery or the right and left pulmonary arteries originate from the side or posterior aspect of the truncal artery at varying distances above the truncal valve. Most commonly, the truncal valve is trileaflet and overrides a high ventricular septal defect. Nearly one-half of the valves have two or four leaflets; all truncal valves exhibit varying degrees of dysplasia and may be regurgitant, stenotic, or both. Often, the main pulmonary artery originates from the left side of the truncus arteriosus and divides into left and right branches that traverse in the usual manner to their respective lungs. This form has been classified as type I by Collett and Edwards. In type II, the right and left pulmonary arteries originate adjacent to each other from the side or back of the truncal artery. In type III, each pulmonary artery originates from different parts of the truncal artery (Fig. 27-1). Type IV, when the lungs are supplied by two pulmonary arteries originating from the descending thoracic aorta, is now considered not a true truncus arteriosus but a form of pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect. Associated anomalies include interrupted aortic arch as well as coronary artery abnormalities.

Most centers now perform primary repair of truncus arteriosus at the time of presentation to prevent the development of irreversible pulmonary vascular disease. Pulmonary artery banding is no longer recommended because it carries a high mortality. In symptomatic neonates who respond to medical management of their heart failure, surgery may be delayed for a few weeks. However, continued symptoms should prompt urgent surgical intervention. Patients presenting at older than 12 months of age should have preoperative cardiac catheterization to assess pulmonary vascular resistance and suitability for repair.

Incision

A median sternotomy is the approach of choice.

Technique

The ascending aorta is cannulated as distally as possible, and bicaval cannulation is achieved. The anatomy is well evaluated, and the right and left pulmonary arteries are dissected circumferentially. Tapes are passed around the pulmonary arteries so that they can be occluded just before the initiation of cardiopulmonary bypass.

The aortic cannula should be placed at the level of the innominate artery to ensure adequate exposure of the pulmonary arteries after the cross-clamp is applied.

It is essential to dissect both pulmonary arteries so that they can be encircled and occluded as soon as cardiopulmonary bypass is initiated. This prevents runoff of arterial flow from the pump into the lungs, which leads to inadequate systemic and coronary perfusion and flooding of the pulmonary circulation.

When cardiopulmonary bypass is initiated, the pulmonary artery snares are tightened, and systemic cooling is begun.

If significant truncal valve insufficiency is present, the heart may distend as soon as cardiopulmonary bypass is begun. A vent should be immediately placed through the right superior pulmonary vein into the left ventricle (see Chapter 4). If regurgitation is severe, a large amount of the aortic line return may be retrieved by the left ventricular vent, leading to inadequate systemic perfusion. In this case, the truncal artery must be clamped immediately and opened so that cardioplegic solution can be administered directly into the coronary arteries.

The truncus is cross-clamped, and cardioplegic solution is administered into the truncal root. The main pulmonary artery is detached from the truncal artery (Fig. 27-2A), and the defect is closed, usually in a horizontal manner, with a continuous 6-0 Prolene suture (Fig. 27-2B). In type II or III defects, the pulmonary arteries are detached in continuity, leaving a rim of aortic tissue attached to their origins. The resulting defect in the truncal artery is closed.

If the defect is too large and direct closure of the truncal artery (now the aorta) would result in distortion of the truncal valve or aorta, an autologous pericardial or GORE-TEX patch of appropriate size is used to close the defect (Fig. 27-2C).

The main or right and left pulmonary arteries should be excised in continuity with adequate surrounding tissue. Often, this can be best accomplished by transecting the truncal artery just above the pulmonary arteries, excising the orifices of the pulmonary arteries, and then performing an end-to-end anastomosis of the ascending aorta to the truncal root. This technique necessitates adequate mobilization of the distal ascending aorta, aortic arch, and arch vessels to prevent undue tension on the aortic suture line.

The left coronary artery may be located high on the posterior wall of the truncal root. Care must be taken when closing the aortic defect not to injure the left coronary artery.

The snares on the pulmonary arteries must be kept in place until after the cardioplegic solution has been delivered. Otherwise, the cardioplegia will run off into the pulmonary circulation and inadequate amounts will reach the coronary bed. When significant truncal valve insufficiency is present, cardioplegic solution should be delivered directly into the coronary ostia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree