INDICATIONS FOR TRANSTHORACIC APPROACH

Consideration of antireflux surgery is appropriate under several circumstances, which are well documented in Chapters 1 and 3. Briefly, operation is reasonable to consider when the patient’s symptoms persist despite medical management, there are reflux complications such as continuing regurgitation, persistent esophagitis or stricture, or repair of a giant hiatal hernia is necessary.

Absolute Indications

The majority of patients needing first operations for GERD or giant hiatal hernia can and should be operated with a laparoscopic approach. There are few absolute indications for a thoracic approach. An important instance is when the need to resect the distal esophagus is a distinct possibility. Examples of this scenario include patients with a chronic stricture that is resistant to dilation or who have a distal esophagus anatomically or functionally damaged by prior operations. Preserving a poorly or nonfunctional esophagus is not a surgical victory. Replacing the diseased esophagus with a healthy and functional alternative such as a colonic or jejunal interposition, while a significant undertaking, is preferable as it gives the patient the best postoperative quality of life. Patients particularly at risk for needing and benefitting from resection and reconstruction with healthy tissue, such as the left colon, are those having a second or even third reoperation (i.e., a third or fourth operation). If resection is required and the surgeon is in the abdomen through a laparotomy, it may not be possible to get cephalad to the damaged esophagus to perform an anastomosis to healthy, functional esophagus through the hiatus. Of course, if the surgeon has performed a left thoracotomy but a resection is not necessary, nothing is lost as an antireflux operation is performed through the left chest with the transthoracic exposure providing the opportunity to generously mobilize the esophagus and add a Collis gastroplasty. Another occasional reason for a thoracic approach, in addition to the concern that a resection will be required, is when a patient has other thoracic pathology requiring attention, such as a lung mass.

Relative Indications

Relative indications for choosing a thoracic approach include the uncommon short esophagus associated with chronic reflux and/or stricture or giant hiatal hernia. My experience is that the short esophagus is an acquired condition caused by chronic and uncontrolled reflux producing fibrosis and scarring, rather than being a congenital condition. Although a laparoscopic approach, including performance of a Collis gastroplasty is possible, in this situation a surgeon may feel that the thoracic approach allows helpful access to perform mobilization of the mediastinal esophagus and provides the historically standard approach for performance of a Collis gastroplasty, two steps in ensuring a tension-free reduction of the gastric wrap below the diaphragm, an essential component of a successful antireflux procedure. Another relative indication for choosing to operate through a thoracotomy is a patient having a redo procedure and the surgeon considers a thoracic approach necessary because of improved access to the cardia and the ability to mobilize the thoracic esophagus to obtain sufficient length for a tension-free reduction of the fundoplication below the diaphragm. This is an issue of surgical judgment and experience as reoperation can be carried out by laparotomy or even laparoscopy. The same scenario applies to repair of giant or paraesophageal hiatal hernias, which some surgeons still prefer to repair transthoracically. Finally, significant obesity increases the challenge of the abdominal approach; however, if patients are morbidly obese, they are better served by a bariatric procedure which addresses both the obesity and the reflux. These relative indications for a transthoracic approach are all issues of the judgment and experience of the operating surgeon.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

To delineate the anatomy and assess the status of the esophagus and stomach, both upper gastrointestinal x-rays and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (ideally by the operating surgeon) should be performed. Depending on the preoperative diagnosis, functional studies including pH monitoring and esophageal motility studies are important. If the planned procedure is a reoperation, the operative notes from the earlier operations should be reviewed, so there is knowledge of what and how tissues have been dissected and/or divided and motility evaluation is essential so the surgeon can predict the ability of the esophagus to function sufficiently postoperatively.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Surgical Access

Thoracic antireflux procedures are performed through a left lateral thoracotomy in the sixth or seventh interspace. A posterior extension is not necessary. If access to the abdomen is required, the lower interspace provides better visibility below the diaphragm and the incision is carried anteriorly to within 5 cm of the costal margin, but not across, as dividing the costal margin is quite painful and not necessary. For adequate exposure of the operative field, I encourage dividing the latissimus dorsi routinely. The serratus is partially divided as necessary for visibility. Resecting a portion of the inferior rib posteriorly, beneath the mobilized erector spinae muscle allows rib spreading without unintended fractures, again minimizing postoperative pain.

The ipsilateral lung is deflated with the use of a double-lumen endotracheal tube, all adhesions from previous operations are lysed, the inferior pulmonary ligament is divided up to the inferior pulmonary vein, and the collapsed lung is packed out of the field with a moist laparotomy pad. The mediastinal pleura is incised, and the esophagus is delivered with finger dissection and held with a Penrose drain. If there is scarring from previous operative dissection, it is best to start the mediastinal dissection cephalad to areas of previous dissection, so the esophagus can be identified and mobilized easily and safely. Both vagus nerves should be surrounded with the Penrose drain and brought with the esophagus as dissection proceeds to free the esophagus from just inferior to the aortic arch to the hiatus.

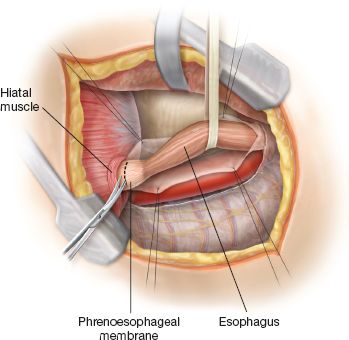

If this is the patient’s first operation, the cardia can be mobilized through the hiatus. The dissection is begun by incising the phrenoesophageal membrane and peritoneum anteriorly (Fig. 4.1). The surgeon then can control the dissection with the index finger of the left hand and thumb grasping the distal esophagus in the abdomen and controlling the cardia through the incision in the phrenoesophageal membrane (Fig. 4.2). With this control, the hiatus is dissected until the distal esophagus and cardia are completely free. The vagus nerves are protected both by tactile and visual tracking during the mobilization. To construct a Belsey Mark IV fundoplication, no further dissection is usually required. For a Nissen fundoplication, division of enough of the short gastric vessels to allow the fundus to be adequately delivered into the chest is necessary. This is done by exerting gentle traction on the fundus so that these vessels can be sequentially identified, ligated, and divided as they emerge through the hiatus (Fig. 4.3). This sufficiently mobilizes the fundus so that a wrap can be performed. It must be kept in mind that the wrap is being constructed in an artificial location, that is, the chest, but will be returned to and reside in the abdomen, which means truly needing a “floppy” fundus so it can reach up through the hiatus.

In the instance of a reoperation, this complete mobilization at the hiatus and of the fundus cannot be adequately and safely completed through the hiatus because of scarring and adhesions to the hiatus and, intra-abdominally, between the cardia/fundus and the diaphragm, retroperitoneum, and liver. The original gastric wrap is also typically adhesed to the fundus and terminal esophagus and original sutures are still present, even if the wrap has herniated and/or partially dehisced. To safely attain needed mobilization, dissection within the abdomen is necessary. This access is gained by incising the diaphragm peripherally, 2 to 3 cm from the chest wall attachment, starting anteriorly at the pericardial fat pad and going posteriorly as needed, usually far enough to provide exposure of the gastrosplenic ligament and its short gastric vessels (Fig. 4.4). Dissection then proceeds from above and below the hiatus until the distal esophagus, cardia, and proximal fundus are free of adhesions and are mobile. The preexisting wrap, which is typically partially dehisced and/or around the stomach rather than the esophagus, is taken down. This requires cutting the original fundus-to-fundus sutures. At the conclusion of the operation, the diaphragmatic incision is closed with a series of interrupted or near/far–far/near sutures.

Figure 4.1 After fully mobilizing the esophagus, the phrenoesophageal membrane is identified beneath the hiatal muscle rim anteriorly and incised, providing access to the abdomen.