INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Esophageal dilation is indicated for the treatment of dysphagia caused by esophageal-obstructing pathologies and functional disorders (Table 35.2). Achalasia, malignant strictures, and postoperative anastomotic strictures constitute the most common indications.2 Peptic strictures are also an indication, although the incidence of peptic strictures has markedly declined since the introduction of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

The clinical goal of esophageal dilation is the relief of dysphagia by eliminating the obstructing process in the esophagus. This allows maintenance of adequate oral nutrition and prevents aspiration. Dysphagia is usually significantly improved when a luminal diameter of 12 to 15 mm is achieved or at least a 36F dilator is passed. Maintenance of a 15-mm-diameter lumen (45 French) generally allows near normal dietary intake. Dilation of an obstructing esophageal lesion also allows the passage of the endoscope to the stomach for gastroscopy, the endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) probe for evaluation of the esophageal pathology, and for the potential placement of a stent. Large diameter esophageal dilators (50 to 60 French) are also frequently used intraoperatively during the creation of a fundoplication to lower the risk of iatrogenic dysphagia.3 Similarly, these dilators can be used to treat postfundoplication dysphagia. Early dilation has been cited by many experienced esophageal surgeons to be beneficial in the early management of esophageal anastomotic leaks to help preserve a distal patent lumen and facilitate fistula closure. In other settings, esophageal dilation may be required prior to placement of an expandable stent.

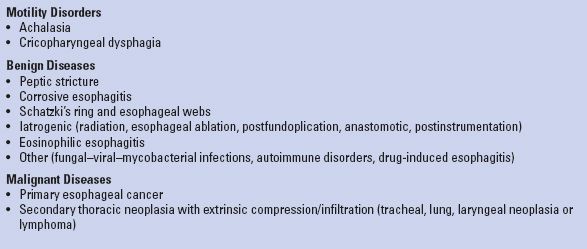

TABLE 35.2 Most Common Indications for Esophageal Dilation

Active esophageal perforation is an absolute contraindication to esophageal dilation. History of previous esophageal perforation is a relative contraindication to future dilations and extreme caution should be used. Conditions that increase the difficulty of the procedure and increase the risk of perforation or other complications also constitute relative contraindications. This includes esophageal malignancy, large thoracic aortic aneurysms, and pharyngeal or cervical deformities including vertebral bone spurs, compromised cardiorespiratory status, and severe coagulopathy. Radiotherapy and concurrent esophageal biopsies are not considered contraindications to esophageal dilation.4,5

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Candidates for esophageal dilation should be thoroughly evaluated prior to the procedure to determine the cause of the esophageal obstruction as well as the procedural risks associated with the patients’ comorbidities. History should be taken and physical examination performed before making the decision to intervene. A barium swallow is obtained to assess the extent and nature of the obstruction, although endoscopic assessment is essential as well. It should be noted that patients with proximal dysphagia may be harboring other pathologies (i.e., pharyngeal pouch, Zenker’s diverticulum, postcricoid web) that increase the risk of perforation. Other available imaging studies should also be reviewed.

Endoscopy provides valuable information on the anatomic site, the length, and the nature of the obstructing lesion. Biopsies or brush cytology should be performed to detect malignancy, which would affect the overall management and may increase the risk of perforation. Other endoscopic findings, such as hiatal hernia, tortuous esophagus, angulation of the stricture, and esophageal diverticula can also influence the decision on the type of dilators that need to be used. Simple strictures can be biopsied and dilated in the same session, while suspicion of malignancy may defer dilation due to the increased risk of perforation.

The procedure should be explained in detail to the patient. The anticipated benefits, the alternative treatment options, and the potential risks should be discussed, and consent should be obtained.

Esophageal dilation can cause bleeding in patients receiving anticoagulants, which may be difficult to control endoscopically. Therefore, warfarin should be discontinued prior to the dilation, and a prothrombin time test should be performed. In patients at high risk for thromboembolic events, bridging with heparin may be considered. Heparin should be withheld 4 to 6 hours prior to the procedure and resumed 4 to 6 hours after. Warfarin can typically be restarted on the night of the procedure. There is no solid data indicating the need to discontinue aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications prior to esophageal dilation. However, antiplatelet agents like clopidogrel should be discontinued 7 to 10 days prior to the procedure.

The patients fast for 4 to 6 hours prior to the procedure to ensure that the stomach and the esophagus are empty for the procedure. This is essential not only for a technically successful endoscopy and dilation, but also for prevention of aspiration. Achalasia patients, who develop severe esophageal stasis, may require longer fasting.

Transient bacteremia with esophageal dilation has been observed.6 Therefore, preprocedure antibiotics should be administered to patients at risk for endocarditis and patients with immunosuppression. The guidelines on antibiotic coverage for endoscopy should be followed.

Although upper endoscopy and esophageal dilation may be performed on awake patients, deeper levels of sedation or even general anesthesia may be required for the patient’s comfort during the procedure. The type of sedation is decided on the basis of the patient’s overall health condition, the expected duration and type of intervention, the patient’s previous tolerance to common sedative medications, and the preferences of the endoscopist. Most commonly, sedation is obtained with intravenous midazolam, fentanyl, or propofol. Continuous pulse oximetry and hemodynamic monitoring are provided. Spraying the oropharynx with lidocaine or asking the patient to swallow viscous lidocaine prior to the procedure can make the endoscopy and dilation more comfortable, but is generally not needed. Under specific circumstances, general endotracheal anesthesia is required or may be preferred by some patients.

The plan on which approach and what type of dilator will be used should be formulated before the procedure and finalized during the endoscopy based on the findings. Nonguided bougies (Maloney) can be used with simple strictures, webs, or rings in a fairly straight esophagus. However, it must be noted that esophageal perforation is always a consideration and may be mitigated by fluoroscopy, guidewires, and endoscopic direct visualization. Patients with particularly refractory and straightforward strictures, such as cervical radiation or anastomotic strictures, can be taught to use these types of bougies at home. Tighter or more complex strictures are approached with guided dilators, either TTS balloons or push dilators (Savary-Gilliard). The use of contrast and fluoroscopy enhances the safety of the intervention in difficult situations. The experience and facility of the endoscopist with a specific type of dilator also play a key role in the decision making.4

SURGERY

SURGERY

Principles

Despite the specific differences in the technique used, there are some principles that apply to all the types of esophageal dilation. (a) The size of the first dilator used, either balloon or bougie, should correspond to the diameter of the stricture; (b) Traditionally, it is advised that no more than three bougie dilators of sequentially increasing size should be used in every one session (“rule of three”). Multiple sessions may be required for the desired total dilation; (c) The clinical end point of esophageal dilation is the relief of dysphagia. It has been suggested that luminal diameter of 12 to 15 mm suffices for unobstructed swallowing. Esophageal webs or Schatzki’s rings require larger-caliber dilators (16 to 20 mm), whereas treatment of achalasia is attempted with even larger dilators (30 to 40 mm). The risk of perforation, though, increases linearly with the size of the dilator. Caution should be used when malignant strictures are dilated because of the higher risk of perforation. Dilation should be gentle and wide enough to allow biopsy, passage of the EUS probe, and palliative stent placement; (d) Dilation of the stenotic lesion starts when moderate resistance is encountered during passage of the bougie through the stricture or during balloon inflation. Excessive resistance should be avoided, since rupturing forces are developing.

Positioning

Most commonly, the patient is placed in the left lateral decubitus position, which is the typical for upper endoscopy. This allows the use of all types of esophageal dilators and does not interfere with patient monitoring, while it facilitates the management if intraoperative regurgitation occurs and minimizes the risk of aspiration. The supine position can be used when general endotracheal anesthesia is administered or fluoroscopy is planned, in order to improve the view without the overlying humerus. Transnasal, office-based esophageal dilations have also been reported in the sitting position.7 Dilation with Maloney bougies can be done in the sitting position as well, particularly when self-dilations are performed.

Push Dilators

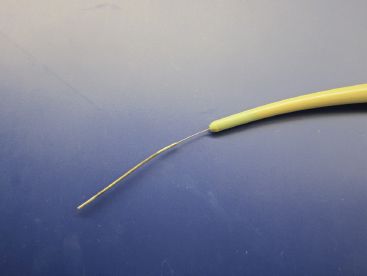

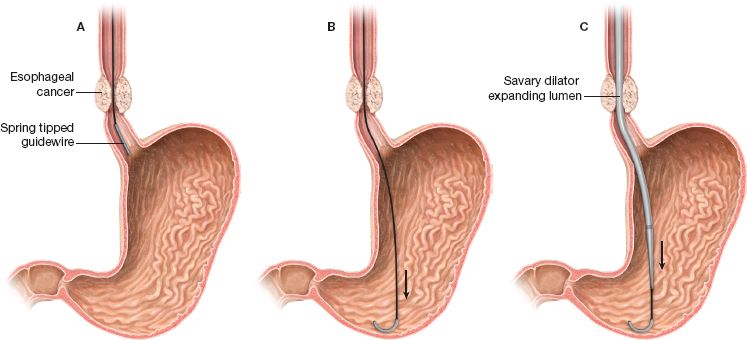

The guided passage of push dilators, such as the Savary-Gilliard, lowers the risk of perforation. These dilators have a central lumen which allows their advancement over a stiff guidewire with a soft spring tip (Savary guidewire) (Figs. 35.1 and 35.2). Softer guidewires can be used with caution when more complex strictures need to be negotiated. However, these may be too flexible to direct the dilator and can lead to perforation.

Figure 35.1 Savary-Gilliard dilator with guidewire in place.

The guidewire is advanced through the working channel of the endoscope and its tip is preferably positioned in the antrum or positioned through the pylorus into the duodenum. If the stricture cannot be traversed by the endoscope, a pediatric endoscope might transverse the stricture, or a guidewire can be passed using endoscopic vision and fluoroscopic guidance through the stricture and into the stomach. Subsequent fluoroscopic controlled bougienage can then be performed. Alternatively, a dilating balloon catheter can be similarly passed through the narrowing, and dilation performed. Typically, the endoscope can be subsequently passed through the dilated stricture into the stomach for full evaluation of the esophagus and stomach. Alternatively, the guidewire can be placed under fluoroscopy ensuring that the tip passes at least 20 to 30 cm distal to the stenotic lesion. Endoscopic use of contrast may improve the evaluation of the stricture intraoperatively.

After proper positioning of the guidewire, the endoscope is withdrawn slowly with synchronous equal advancement of the guidewire through the working channel so that the tip of the wire remains stable. This is the standard Seldinger technique also used for advancement of central vascular access catheters. This task is more easily performed by the coordinated actions of two people and can be monitored either endoscopically or under fluoroscopy. As soon as the tip of the endoscope is outside the patient’s mouth, the guidewire is grasped and stabilized against the bite-block. The guidewire is marked for depth and the position should be noted before passing the dilator to make sure that the guidewire tip has remained in the stomach.

Figure 35.2 Esophageal dilation technique using the Savary-Gilliard dilator.