Transhiatal Esophagectomy Without Thoracotomy

Mark B. Orringer

Historically, in 1913 Denk performed the first reported blunt transmediastinal esophageal resection, without thoracotomy, using a vein stripper in cadavers.20 In 1933, the British surgeon Turner reported the first successful transhiatal blunt esophagectomy for carcinoma and used an antethoracic skin tube to reestablish alimentary continuity at a second stage.108 With the advent of endotracheal anesthesia, however, esophageal resection under direct vision became possible, and transhiatal esophagectomy (THE) without thoracotomy became a seldom-used procedure reserved primarily for the patient undergoing a laryngopharyngectomy for carcinoma and restoration of alimentary continuity with the stomach.53,69 As transthoracic operations became a reality, reports of resection of the thoracic esophagus—including those by Rehn (1898),92 Llobet (1900),55 and Torek (1915)106—began to appear.

The earliest reports of successful transthoracic esophagectomy and intrathoracic esophagogastric anastomosis for carcinoma were by Ohsawa in 1933,67 Marshall in 1938,58 Adams and Phemister in 1938,1 and Churchill and Sweet in 1942.16 Garlock 194629 and Carter 194713 popularized the combined left thoracoabdominal incision for carcinoma of the lower third of the esophagus, which had been used by Ohsawa.67 In 1946, Ivor Lewis54 described a right combined thoracic and abdominal approach for esophageal resection and reconstruction, citing the advantages over a left-sided approach of improved access to the upper two-thirds of the esophagus, exposure of the entire course of the esophagus after division of the azygos vein, and protection of the opposite pleural cavity provided by the descending thoracic aorta. Ong68 used a right thoracotomy for resection of middle-third esophageal tumors but advocated a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. McKeown61,62 also preferred a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis and described his use of three incisions (i.e., laparotomy, right thoracotomy, and cervical) for resection of esophageal carcinoma and esophageal reconstruction with stomach. But some variation of a thoracoabdominal esophageal resection and reconstruction with an intrathoracic esophagogastric anastomosis was the most popular approach into the 1980s.

With the exception of a few reported series of transthoracic esophageal resection and reconstruction for carcinoma performed with a hospital mortality <5% by Akiyama and associates,2 Mitchell,64 and Mathisen and colleagues,60 this operation remained a formidable one in the hands of surgeons worldwide, with mortality rates ranging from 15% to 40% in series reported through the 1970s and early 1980s,28,86 and averaging 33%.27,32 In reports published between 1980 and 1990, the mean mortality rate for resection of esophageal carcinoma, although nearly halved compared with the previous decade, was still 13%.65 Pulmonary complications caused by splinting and atelectasis associated with a combined thoracic and abdominal operation in a debilitated patient with esophageal obstruction, and mediastinitis and sepsis after an intrathoracic esophageal anastomotic leak, remained the leading causes of death after esophageal resection in virtually every reported series.

Against this backdrop of more than 40 years of experience with transthoracic esophageal resection, Orringer and Sloan,81 in 1978 reawakened interest in the technique of THE without thoracotomy as an alternative approach with potentially less risk and morbidity than the more traditional transthoracic resection. By avoiding a thoracotomy, it was argued that this approach lessens the physiologic impact of a combined thoracic and abdominal operation. Furthermore, mediastinitis from an anastomotic leak is virtually eliminated, since the cervical esophageal anastomosis results in a transient, easily drained salivary fistula if a leak occurs. The technique of THE was criticized by some as being an unsafe operation that violates basic surgical principles of adequate exposure and hemostasis and denies the patient with carcinoma a complete mediastinal lymph node dissection. After 1978, a number of published reports described several surgeons’ early experience with THE and discussed the indications and relative morbidity and mortality of transhiatal versus transthoracic esophagectomy. Many of these THE series represented the authors’ early results with this procedure, and they were not reflective of the true morbidity and mortality of the operation performed after greater experience and facility with it were gained. Katariya and colleagues50 (1994) reviewed 1,353 patients undergoing THE who were reported in the surgical literature between 1981 and 1992. Sixteen of the papers referenced (69.5%) were series of 50 patients or less and as such were not a true reflection of the types of results that can be achieved by more experienced surgical teams. All but 12 of the operations were for cancer. Eighteen (1.3%) were converted to open thoracotomies for control of hemorrhage. Tracheal injuries occurred in nine (0.67%). The most common

postoperative complications were “thoracic or pulmonary,” which these authors grouped together as including pneumo- thoraces, pleural effusions, pneumonias, empyemas, and respiratory failure, and which occurred in nearly 50% of the patients. Such an inclusive complication category is difficult to analyze. The need for a chest tube because of entry into a pleural cavity is much less of a complication than pneumonia, empyema, or respiratory failure, which prolong hospitalization. Additional complications included anastomotic leak (15.1%), clinically detected recurrent laryngeal nerve injury (11.3%), cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial infarction or tamponade (11.9%), incidental splenectomy (2.6%), and chylothorax (0.7%).

postoperative complications were “thoracic or pulmonary,” which these authors grouped together as including pneumo- thoraces, pleural effusions, pneumonias, empyemas, and respiratory failure, and which occurred in nearly 50% of the patients. Such an inclusive complication category is difficult to analyze. The need for a chest tube because of entry into a pleural cavity is much less of a complication than pneumonia, empyema, or respiratory failure, which prolong hospitalization. Additional complications included anastomotic leak (15.1%), clinically detected recurrent laryngeal nerve injury (11.3%), cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial infarction or tamponade (11.9%), incidental splenectomy (2.6%), and chylothorax (0.7%).

In the next decade, there were at least nine different reports on THE and 37 series comparing transthoracic esophagectomy and THE. Table 138-1 lists the series, totaling more than 6,300 patients.

In a more recent meta-analysis of transthoracic versus transhiatal resection for carcinoma of the esophagus by Hulscher and associates44 (2001), perioperative blood loss was significantly higher after transthoracic resection (mean 1,001 mL versus 728 mL), and transthoracic resection carried a higher risk for pulmonary complications, chylothorax, and wound infection. The overall mean anastomotic leak rate was greater with transhiatal resection (13.6% versus 7.2%), as was the rate of vocal cord paralysis (9.5% versus 3.5%). The length of postoperative intensive care after transthoracic resection was significantly longer (11.2 days versus 9.1 days), and the hospital stay significantly prolonged (21 days versus 17.8 days). The overall hospital mortality rate was significantly higher after transthoracic resections (9.2% versus 5.7%). There was no significant difference in survival at 3 or 5 years postoperatively between those undergoing transthoracic and transhiatal esophagectomies. The author and colleagues reported the largest THE series in 2007 and described a 30-year retrospective experience with this operation in 2,007 patients undergoing esophageal resection for diseases of the intrathoracic esophagus, 482 (24%) with benign disease and 1,525 (76%) with carcinoma; the total hospital mortality rate for the procedure was 3%, 1% in the last 1,000 patients.76

General Considerations

THE has been possible in 98% of patients requiring an esophagectomy for either benign or malignant disease at the author’s institution. Without question, the comfort level with this procedure is far greater than it was 25 to 30 years ago and this in part explains the general use of THE in virtually all of the author’s patients requiring an esophagectomy. In patients with esophageal carcinoma, the operation is contraindicated if there is bronchoscopic evidence of tracheobronchial invasion, not contiguity, by the tumor. Histologic documentation of distant metastatic disease (i.e., biopsy-proven liver or supraclavicular or distant lymph node metastasis) associated with an intrathoracic esophageal carcinoma should be a contraindication to esophagectomy, because these patients with stage IV carcinomas have an average survival of approximately 6 months, and the risks of esophagectomy generally outweigh the short-term benefits in this population.

The preoperative staging of esophageal carcinoma has been greatly improved and refined with the availability of computed tomography (CT), endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), and positron emission tomography (PET), all of which are now regarded as a basic in the preoperative assessment of these patients.51,95 CT scanning of the chest and upper abdomen in the preoperative assessment of these patients is helpful in defining the local extent of the tumor and the presence of distant metastatic disease, but this diagnostic modality is not a reliable indicator of resectability.89,110 CT demonstration of contiguity of an esophageal tumor with adjacent organs does not prove that invasion is present or that the tumor is unresectable.88 Endoscopic ultrasonography, by defining the five layers of alternating echogenicity of the esophageal wall, allows precise determination of the depth of tumor invasion (“T status”), but the value of this study is highly dependent upon the equipment and

technique used as well as operator experience. PET scanning has become an integral part of the assessment of the patient with esophageal carcinoma, often detecting occult metastatic disease not otherwise evident.7,56 EUS, is similarly now performed routinely in the evaluation of all patients with carcinoma being considered for operation.41,91,96 EUS provides what is perhaps the best assessment of the depth of tumor invasion of the wall of the esophagus and adjacent organs and the presence of lymph node metastases that may preclude resection. The addition of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy of suspicious paraesophageal and celiac axis lymph nodes at the time of EUS greatly enhances the accuracy of staging. In patients with benign esophageal disease, particularly those who have had previous esophageal operations and especially an esophagomyotomy, which may produce adhesions between the esophageal submucosa and adjacent aorta, the surgeon must be prepared to convert to a transthoracic esophagectomy if, on palpation of the esophagus through the diaphragmatic hiatus, periesophageal adhesions are found that would prevent a safe transhiatal resection.

technique used as well as operator experience. PET scanning has become an integral part of the assessment of the patient with esophageal carcinoma, often detecting occult metastatic disease not otherwise evident.7,56 EUS, is similarly now performed routinely in the evaluation of all patients with carcinoma being considered for operation.41,91,96 EUS provides what is perhaps the best assessment of the depth of tumor invasion of the wall of the esophagus and adjacent organs and the presence of lymph node metastases that may preclude resection. The addition of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy of suspicious paraesophageal and celiac axis lymph nodes at the time of EUS greatly enhances the accuracy of staging. In patients with benign esophageal disease, particularly those who have had previous esophageal operations and especially an esophagomyotomy, which may produce adhesions between the esophageal submucosa and adjacent aorta, the surgeon must be prepared to convert to a transthoracic esophagectomy if, on palpation of the esophagus through the diaphragmatic hiatus, periesophageal adhesions are found that would prevent a safe transhiatal resection.

Table 138-1 Report on Transhiatal Esophagectomies, 1993–2003 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Anesthetic Management

Intra-arterial blood pressure is monitored with a radial artery catheter so that prolonged hypotension resulting from cardiac displacement by the surgeon’s hand inserted into the posterior mediastinum during the transhiatal dissection can be avoided. Two large-bore intravenous catheters, generally placed in peripheral arm veins, should be available for rapid volume replacement if required, but the arms are padded and placed at the patient’s sides during the operation so that the surgeon has unimpeded access to the neck, chest, and abdomen. If central venous pressure is to be monitored intraoperatively, and this is not routine, a right neck vein should be used to keep the left neck free for the operation. An unshortened standard endotracheal tube is used rather than a larger, more bulky double-lumen tube. If a posterior membranous tracheal tear occurs during the transhiatal dissection, the tube can be advanced into the left mainstem bronchus and one-lung anesthesia maintained while the tracheal injury is dealt with. Because transient hypotension caused by cardiac displacement can occur during a transhiatal dissection, inhalation agents are decreased and inspired oxygen concentration increased during this phase of the operation. THE requires a close working relationship between the anesthetist and the surgeon. Intraoperative hypotension does not signal the need for pressor agents but rather for notifying the surgeon so that the hand can be temporarily removed from the mediastinum.

Operative Technique

The patient is positioned supine, the head turned toward the right, and the neck extended by placing a small folded sheet beneath the scapulae. The skin is prepared and draped from the mandible to the pubis and anterior to both midaxillary lines. The arms are padded and placed at the patient’s sides. A table-mounted, self-retaining (upper-hand) retractor is used to facilitate the abdominal operation. Two suction lines, one at the head of the table and one from below, are used routinely. THE is executed in three phases: abdominal, mediastinal, and cervical.

Abdominal Phase

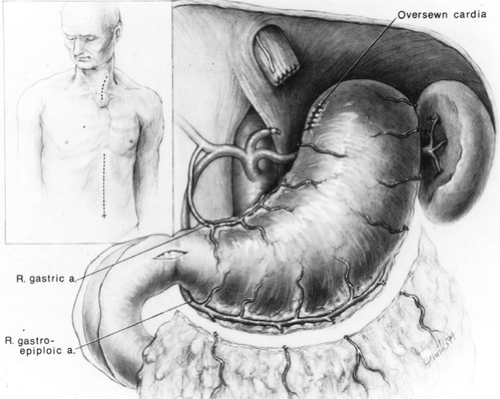

The supraumbilical midline incision extends from the xiphoid to the umbilicus (Fig. 138-1). The triangular ligament of the liver is divided and the left lobe of the liver retracted to the right with a liver blade attached to the upper-hand supporting bar. The stomach is inspected to be certain that scarring or shortening

from prior disease, or involvement of a significant portion of the upper stomach by tumor, does not preclude its use for a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. The right gastroepiploic artery is identified early and protected throughout the operation.

from prior disease, or involvement of a significant portion of the upper stomach by tumor, does not preclude its use for a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. The right gastroepiploic artery is identified early and protected throughout the operation.

Separation of the greater omentum from the stomach is begun high along the greater curvature at an avascular site where the right gastroepiploic artery terminates as it enters the stomach or anastomoses with small branches of the left gastroepiploic artery. The lesser sac behind the greater omentum is entered at this point, and—working progressively upward along the greater curvature of the stomach—the left gastroepiploic and short gastric vessels are divided and ligated sequentially, avoiding both injury to the gastric wall, which may result in later necrosis, and damage to the adjacent spleen. After the high greater curvature of the stomach has been mobilized away from the omentum and spleen, the peritoneum overlying the esophageal hiatus is incised and the esophagogastric junction encircled with a rubber drain. The filmy gastrohepatic omentum is incised, beginning at the midpoint of the lesser curvature of the stomach and proceeding superiorly along the lesser curvature toward the hiatus. The presence of an aberrant left hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery should always be assessed. The left gastric vein is isolated, ligated, and divided. The left gastric artery is isolated, ligated, and divided at its origin from the celiac axis, sweeping all adjacent lymph nodes that can be removed with the specimen toward the stomach. In the presence of an aberrant left hepatic artery, the left gastric artery is dissected and divided at a point that will preserve the hepatic circulation. The right gastric artery is protected throughout the gastric mobilization. Next, the greater omentum along the lower half of the greater curvature of the stomach is separated from the right gastroepiploic artery at least 1.5 to 2.0 cm inferior to the vessel to avoid inadvertent injury to it. A generous Kocher’s maneuver is performed to ensure maximum mobility of the stomach. A pyloromyotomy extending from 1.5 cm on the stomach through the pylorus and onto the duodenum for 0.5 to 1.0 cm is performed using the cutting current of a needle-tipped electrocautery and a fine-tipped mosquito clamp for dissection of the gastric and duodenal muscle away from the underlying submucosa. If the pyloric or duodenal mucosa is violated, the tear is repaired with several 5-0 Prolene (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ) sutures and reinforced with adjacent omentum. Two metallic hemostatic clips are placed adjacent to the pylorus to facilitate its identification on subsequent radiographic examinations. A 14-Fr rubber jejunostomy tube is inserted and secured with a Witzel maneuver. This tube is not brought out through the anterior abdominal wall until the thoracic phase of the operation is completed.

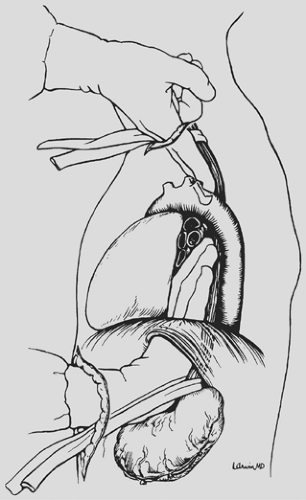

With downward traction on the rubber drain encircling the esophagogastric junction, mobilization of the distal 5 to 10 cm of esophagus from the mediastinum is initiated through the diaphragmatic hiatus (Fig. 138-2). Dissecting bluntly along the prevertebral fascia posterior to the esophagus and anteriorly behind the pericardium, mobility of the esophagus within the posterior mediastinum is assessed through the diaphragmatic hiatus, and if no contraindication exists to proceeding with the THE, attention is now turned to the neck.

Cervical Phase

A 5- to 6-cm incision paralleling the anterior border of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle and beginning just below the cricoid cartilage is used. The platysma and omohyoid fascial layers are divided, the sternocleidomastoid muscle and carotid sheath and its contents are retracted laterally, and the larynx and trachea are retracted medially. No metal retractor should be placed against the tracheoesophageal groove so as to avoid injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Ligation of the middle thyroid vein and inferior thyroid artery is performed when necessary.

The dissection is carried posteriorly to the prevertebral fascia medial to the carotid sheath. The prevertebral space behind the cervical esophagus is developed by blunt finger dissection, constantly keeping the fingers against the esophagus. The tracheoesophageal groove is developed by dissecting posterior to it and against the cervical esophagus to avoid injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The cervical esophagus is encircled with a rubber drain and retracted superiorly as blunt dissection of the upper thoracic esophagus from the superior mediastinum is performed, again keeping the volar aspects of the fingers against the esophagus (see Fig. 138-2). An 8- to 10-cm length of esophagus is mobilized in this fashion down to the level of the carina.

Transhiatal Dissection

THE is performed in an orderly sequential fashion. If the tumor-containing portion of the esophagus feels mobile and

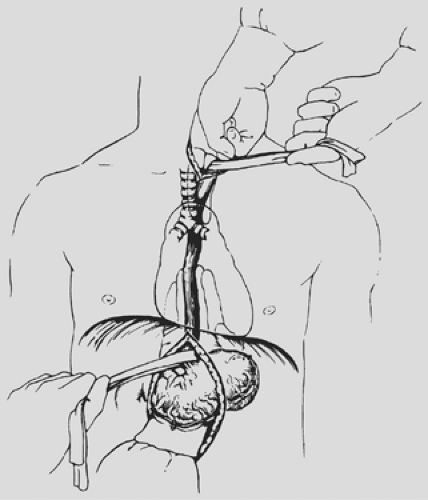

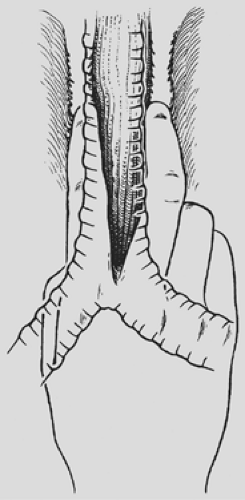

separable from adjacent structures as assessed by grasping the mass through the diaphragmatic hiatus and rocking it, THE is likely possible. The dissection begins posterior to the esophagus. One hand inserted through the diaphragmatic hiatus posterior to the esophagus is advanced superiorly, while the other, inserted through the cervical incision, is advanced downward along the prevertebral fascia. Traction is maintained on both rubber drains encircling either end of the esophagus to facilitate the dissection. A half sponge on a stick is advanced along the prevertebral fascia from the cervical incision until it meets the hand inserted from below through the diaphragmatic hiatus (see Fig. 138-3). Once the posterior mediastinal tunnel is thus established, a 28-Fr Argyle Saratoga sump catheter is inserted through the cervical wound and into the posterior mediastinum; it is then connected to suction at the upper end of the table. This suction catheter maintains a dry field during the subsequent posterior mediastinal dissection and facilitates identification and division of the lateral esophageal attachments under direct vision through the diaphragmatic hiatus. A surgeon whose glove size is larger than 7 or 7.5 may sometimes induce unacceptable hypotension as the hand inserted through the diaphragmatic hiatus displaces the heart. Particular effort should be made to keep the hand flattened posteriorly as close to the spine as possible during the mediastinal dissection, as elevation of the hand anteriorly is more likely to induce hypotension.

separable from adjacent structures as assessed by grasping the mass through the diaphragmatic hiatus and rocking it, THE is likely possible. The dissection begins posterior to the esophagus. One hand inserted through the diaphragmatic hiatus posterior to the esophagus is advanced superiorly, while the other, inserted through the cervical incision, is advanced downward along the prevertebral fascia. Traction is maintained on both rubber drains encircling either end of the esophagus to facilitate the dissection. A half sponge on a stick is advanced along the prevertebral fascia from the cervical incision until it meets the hand inserted from below through the diaphragmatic hiatus (see Fig. 138-3). Once the posterior mediastinal tunnel is thus established, a 28-Fr Argyle Saratoga sump catheter is inserted through the cervical wound and into the posterior mediastinum; it is then connected to suction at the upper end of the table. This suction catheter maintains a dry field during the subsequent posterior mediastinal dissection and facilitates identification and division of the lateral esophageal attachments under direct vision through the diaphragmatic hiatus. A surgeon whose glove size is larger than 7 or 7.5 may sometimes induce unacceptable hypotension as the hand inserted through the diaphragmatic hiatus displaces the heart. Particular effort should be made to keep the hand flattened posteriorly as close to the spine as possible during the mediastinal dissection, as elevation of the hand anteriorly is more likely to induce hypotension.

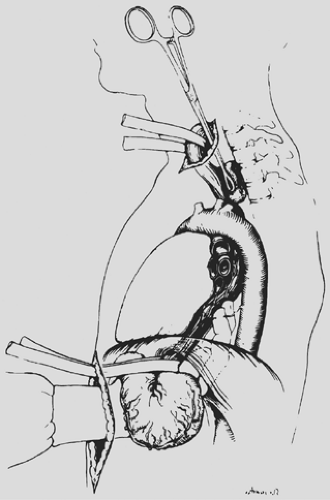

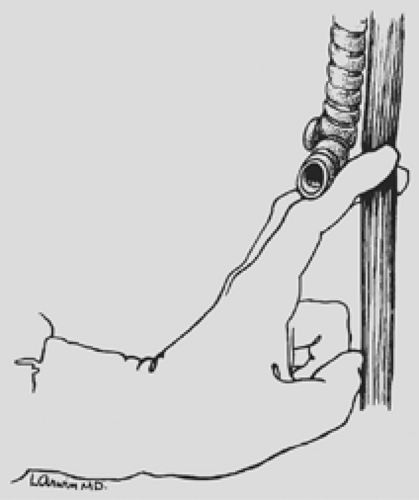

The anterior esophageal dissection is performed as a mirror image of the posterior mobilization, again placing traction on the rubber drains encircling either end of the esophagus and dissecting with the volar aspect of the fingers against the anterior esophagus (Fig. 138-4). As the esophagus is mobilized away from the pericardium and carina, care must be taken to avoid injury to the posterior membranous trachea. With the assistance of narrow retractors placed into the diaphragmatic hiatus, mobile paraesophageal and subcarinal lymph nodes may be dissected with the specimen under direct vision. Long (13-inch) right-angle clamps inserted through the hiatus are used to dissect, mobilize, and clamp the lateral esophageal attachments. These are divided and ligated sequentially. As experience is gained with this procedure, more of the esophageal mobilization is done

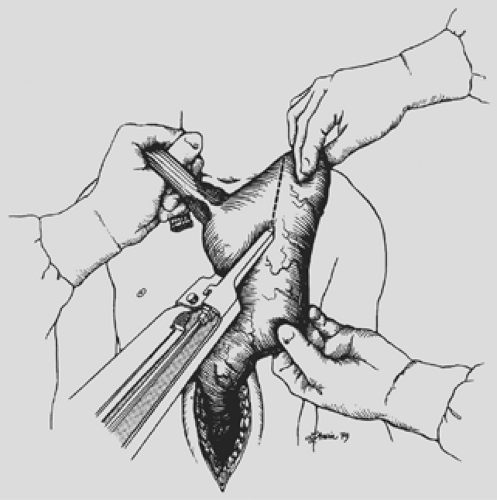

under direct vision through the hiatus, ligating the esophageal attachments. Fingers introduced through the cervical incision dissect downward against the anterior wall of the esophagus, sweeping it away from the trachea and avoiding injury to the posterior membranous trachea (Fig. 138-5). A carefully controlled half sponge on a stick facilitates this anterior dissection. Once the anterior and posterior esophageal dissections have been completed, the lateral esophageal attachments must be divided. Traction is placed on the rubber drain encircling the cervical esophagus to deliver it out of the superior mediastinum. The lateral esophageal attachments are progressively dissected away from the esophagus until 8 to 10 cm of upper esophagus have been circumferentially mobilized. The esophagus is then permitted to retract back into the superior mediastinum. The right hand is inserted through the diaphragmatic hiatus anterior to the esophagus, which is retracted downward by the drain encircling its lower end. The hand is advanced upward into the superior mediastinum until the transition from the circumferentially mobilized upper esophagus to the adjacent segment with its intact lateral attachments can be identified (Fig. 138-6). The esophagus is trapped against the prevertebral fascia between the index and middle fingers, and with a downward raking motion of the hand, the remaining lateral periesophageal attachments are avulsed (Fig. 138-7). During this lateral dissection, vagal fibers passing from the hilum of the lungs onto the esophagus may be hooked by the index finger, identified through the diaphragmatic hiatus, grasped with a long right-angle clamp, divided, and ligated. At times, dense subcarinal or subaortic tissue requires fracture by firm pressure between the index finger and thumb, but this is where judgment must be exercised regarding the need to convert to a transthoracic mobilization of the esophagus under direct vision.

under direct vision through the hiatus, ligating the esophageal attachments. Fingers introduced through the cervical incision dissect downward against the anterior wall of the esophagus, sweeping it away from the trachea and avoiding injury to the posterior membranous trachea (Fig. 138-5). A carefully controlled half sponge on a stick facilitates this anterior dissection. Once the anterior and posterior esophageal dissections have been completed, the lateral esophageal attachments must be divided. Traction is placed on the rubber drain encircling the cervical esophagus to deliver it out of the superior mediastinum. The lateral esophageal attachments are progressively dissected away from the esophagus until 8 to 10 cm of upper esophagus have been circumferentially mobilized. The esophagus is then permitted to retract back into the superior mediastinum. The right hand is inserted through the diaphragmatic hiatus anterior to the esophagus, which is retracted downward by the drain encircling its lower end. The hand is advanced upward into the superior mediastinum until the transition from the circumferentially mobilized upper esophagus to the adjacent segment with its intact lateral attachments can be identified (Fig. 138-6). The esophagus is trapped against the prevertebral fascia between the index and middle fingers, and with a downward raking motion of the hand, the remaining lateral periesophageal attachments are avulsed (Fig. 138-7). During this lateral dissection, vagal fibers passing from the hilum of the lungs onto the esophagus may be hooked by the index finger, identified through the diaphragmatic hiatus, grasped with a long right-angle clamp, divided, and ligated. At times, dense subcarinal or subaortic tissue requires fracture by firm pressure between the index finger and thumb, but this is where judgment must be exercised regarding the need to convert to a transthoracic mobilization of the esophagus under direct vision.

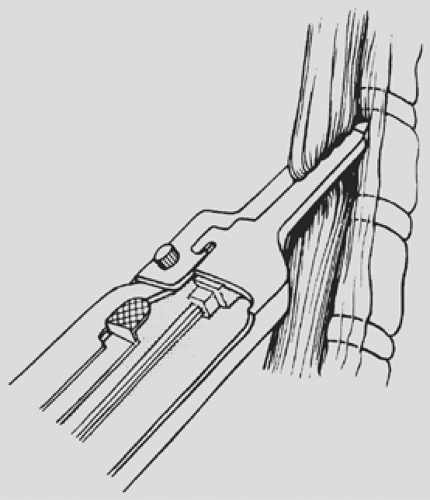

Once the entire intrathoracic esophagus has been mobilized, several inches of esophagus are gently pulled into the cervical wound, and the esophagus is divided obliquely in the neck with the GIA surgical stapler (Fig. 138-8), intentionally leaving redundancy in the length of remaining cervical esophagus that will facilitate later construction of the cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. The stomach is then delivered out of the abdomen, drawing the attached esophagus downward out of the posterior

mediastinum through the diaphragmatic hiatus. Immediately after delivering the esophagus from the posterior mediastinum, narrow, deep Deaver retractors are placed into the diaphragmatic hiatus, the posterior mediastinum is inspected for bleeding from the esophageal bed, and the mediastinal pleura is inspected to determine whether entry into either pleural cavity has occurred and a chest tube is required. A large abdominal gauze pack is inserted through the diaphragmatic hiatus into the posterior mediastinum and left in place to tamponade any minor bleeding as the stomach is prepared for its relocation into the chest. Similarly, narrow-gauge packs are gently inserted through the cervical incision into the upper mediastinum while continually protecting the recurrent laryngeal nerve from direct injury. If entry into either pleural cavity has occurred, a chest tube is inserted as needed low in the respective anterior axillary line.

mediastinum through the diaphragmatic hiatus. Immediately after delivering the esophagus from the posterior mediastinum, narrow, deep Deaver retractors are placed into the diaphragmatic hiatus, the posterior mediastinum is inspected for bleeding from the esophageal bed, and the mediastinal pleura is inspected to determine whether entry into either pleural cavity has occurred and a chest tube is required. A large abdominal gauze pack is inserted through the diaphragmatic hiatus into the posterior mediastinum and left in place to tamponade any minor bleeding as the stomach is prepared for its relocation into the chest. Similarly, narrow-gauge packs are gently inserted through the cervical incision into the upper mediastinum while continually protecting the recurrent laryngeal nerve from direct injury. If entry into either pleural cavity has occurred, a chest tube is inserted as needed low in the respective anterior axillary line.

The mobilized stomach and attached esophagus are placed on the anterior chest, and the gastric fundus is grasped and retracted superiorly. For tumors of the distal esophagus and cardia, an area along the lesser curvature at the level of the second vascular arcade from the cardia is cleared of fat and blood vessels between clamps and ties. The gastric fundus is retracted superiorly, as the lesser curvature of the stomach is progressively divided with sequential applications of the 5-cm GIA stapler approximately 4 to 6 cm distal to palpable tumor (Fig. 138-9). After each application of the stapler, the stomach is progressively stretched cephalad, thereby straightening the natural bend of the lesser curvature to the right and maximizing the upward reach of the stomach. For tumors of the upper

and middle esophagus and in cases of benign disease requiring esophagectomy, as little stomach as possible is sacrificed to preserve gastric submucosal collateral circulation to the fundus. After dividing the proximal stomach, the esophagus is removed from the field and the gastric staple suture line is oversewn with a running 4-0 monofilament absorbable suture. Traction on the stomach should be maintained as the suture line is oversewn to avoid “purse stringing” the lesser curvature and interference with the upward reach of the stomach.

and middle esophagus and in cases of benign disease requiring esophagectomy, as little stomach as possible is sacrificed to preserve gastric submucosal collateral circulation to the fundus. After dividing the proximal stomach, the esophagus is removed from the field and the gastric staple suture line is oversewn with a running 4-0 monofilament absorbable suture. Traction on the stomach should be maintained as the suture line is oversewn to avoid “purse stringing” the lesser curvature and interference with the upward reach of the stomach.

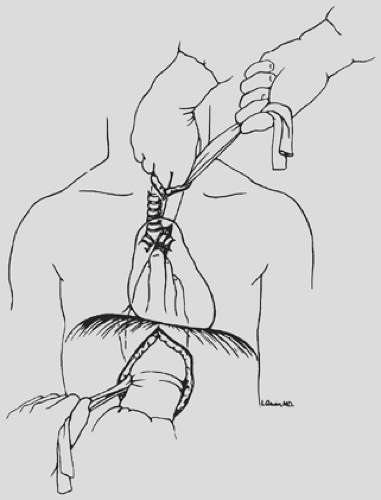

The abdominal pack that was placed into the mediastinum through the diaphragmatic hiatus and those in the superior mediastinum through the cervical incision are now removed, and the entire hand and forearm are inserted through the posterior mediastinum until three fingers emerge from the neck wound to ensure an adequate posterior mediastinal tunnel to accommodate the stomach. The gastric fundus is then grasped gently by the fingertips of one hand, which guide the stomach through the diaphragmatic hiatus and upward anterior to the spine, beneath the aortic arch, and into the superior mediastinum (Fig. 138-10). A Babcock clamp inserted into the superior mediastinum through the cervical incision is used to deliver the gastric fundus into the neck wound until the stomach can be grasped with the fingers and gently pulled upward. Great care is taken to avoid traumatizing the stomach in this process. The Babcock clamp is not completely closed, and the stomach is delivered into the neck more by pushing from below than traction from above. A healthy pink gastric fundus tip in the neck wound is the goal of this repositioning of the stomach. Suturing of the stomach to a rubber traction drain, as originally advocated by the author, suction apparatuses, and bowel bags are avoided to minimize gastric trauma. Typically 4 to 5 cm of stomach is delivered into the neck wound. It is temporarily held in place by a narrow moistened gauze pack inserted into the thoracic inlet posterior to the stomach to prevent the stomach from slipping back into the posterior mediastinum. A moistened gauze is placed temporarily over the neck wound and the color of the stomach intermittently assessed as the abdomen is closed. The anterior surface of the stomach is carefully palpated through the hiatus and the neck incision to be certain that it has not become twisted within the posterior mediastinum during its positioning in the chest. In the rare situation in which mediastinal fibrosis from prior inflammation or irradiation results in posterior mediastinal narrowing that does not accommodate the stomach, it may be necessary to develop a

retrosternal tunnel, resect the sternoclavicular joint, and place the stomach retrosternally.

retrosternal tunnel, resect the sternoclavicular joint, and place the stomach retrosternally.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree