INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Regardless of which technique of esophageal resection is used, it is very important that the operation be well tolerated by the patient with low morbidity and complication rates. It should offer a reasonable expectation to resect all evident tumors without the cost or risk being prohibitive. Treatment is usually palliative, and an outcome that leads to a long drawn-out hospitalization is to be avoided.

Orringer et al.5 have stated that all patients being evaluated for an esophagectomy for benign or malignant disease should be considered potential candidates for THE. We reserve THE for those patients with lower third esophageal malignancies or benign disease. Middle third esophageal cancers are treated by an Ivor Lewis approach or a three-incision technique including laparotomy, thoracotomy, and cervical incision with anastomosis performed in the neck.

Patients who have positive subcarinal lymph nodes picked up either by positron emission tomography (PET) or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) are not offered THE. Those patients are offered Ivor Lewis or three-field dissection. In cases of gastroesophageal junction tumors, if the bulk of the mass is on the gastric side of the GE junction, this is treated as gastric carcinoma with preoperative chemotherapy and esophagogastrectomy by a left thoracoabdominal approach.

At our institution, contraindications to performing THE include middle and upper third lesions, patients with stage IV cancer, and patients who have bronchoscopic evidence of tracheobronchial invasion.

THE can also be performed in patients with periesophageal fibrosis from previous surgeries, corrosive injuries, or radiation therapy. If significant adhesions are encountered during surgery via palpation through the hiatus, the surgeon should be prepared to convert to a transthoracic approach.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The initial history and physical examination of patients with esophageal carcinoma is vital. The presence of palpable adenopathy, stigmata of liver disease, and evidence of malnutrition could indicate unresectability or high operative risk, respectively. A barium swallow is routinely obtained on all our patients.

PET scan has become an integral tool in the preoperative staging of esophageal cancer. It can detect metastatic disease which may preclude resection. PET scan can also be used to determine response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy. EUS is now also used routinely to define the depth of tumor invasion and presence of mediastinal, paraesophageal, and celiac axis nodal metastases. All patients at our institution are evaluated with EUS and PET scans. All patients with T3 or greater tumors or patients who have nodal involvement undergo neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy.

Patients should undergo pulmonary function testing and smoking cessation for at least 2 weeks before THE. All patients receive a cardiology evaluation. When patients have exhibited severe weight loss and dehydration, percutaneous gastrostomy or jejunostomy feeding tubes can be placed. All patients undergo bowel preparation preoperatively in the unlikely event that a colon interposition is needed.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Anesthetic Management

We routinely place an arterial line, triple-lumen catheter, and epidural in all patients. The epidural is vital for postoperative pain control, which then leads to improved pulmonary function. A Foley catheter is inserted at the start of the case. A dose of IV cefazolin and metronidazole is given prior to incision. A standard endotracheal tube is used. During the mediastinal dissection, close cooperation and communication between the surgeon and the anesthesiologist are required as episodes of hypotension can occur during the transhiatal dissection. All patients are given volume expansion with albumin before starting the transhiatal dissection as it appears to prevent hypotension during this stage of the operation. Patients are started on low dose (2.5 mg) of IV dopamine to improve splanchnic blood flow. Both the epidural and IV dopamine are continued for 5 days postoperatively.

Positioning

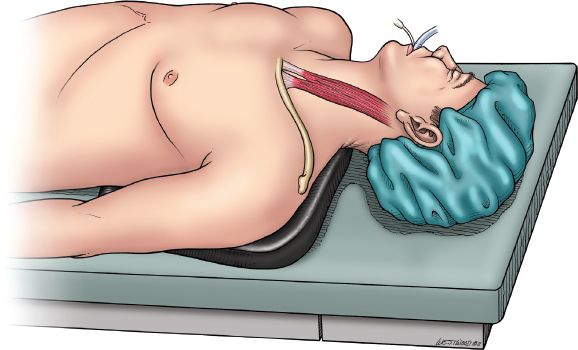

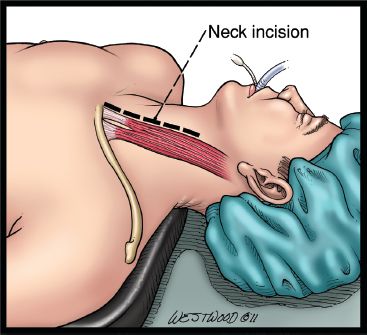

The patient is positioned supine with the head turned toward the right (Fig. 20.1). The neck is extended by placing a gel pad behind the shoulders. The operative field extends from the mandibles to the suprapubic area and anterior to both midaxillary lines. The arms are padded and tucked at the sides. A self-retaining, table-mounted upper abdominal retractor (upper hand retractor) is used to facilitate exposure of the upper abdomen and hiatus (J. Hugh Knight Instrument Co., Slidell, Louisiana). THE is performed in four separate phases—abdominal, transhiatal, cervical, and anastomotic.

Abdominal Phase

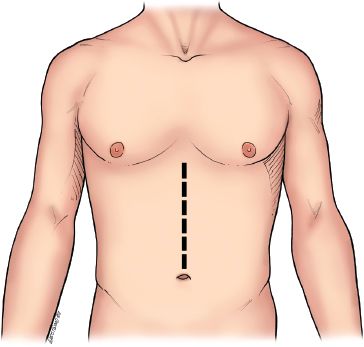

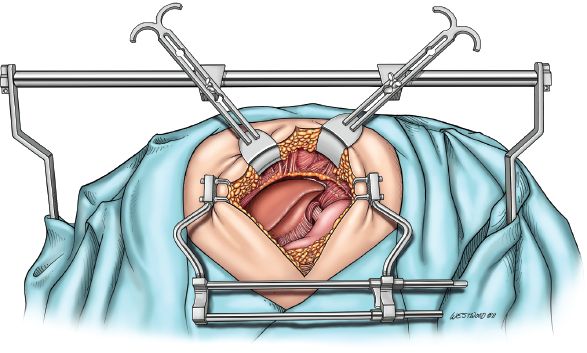

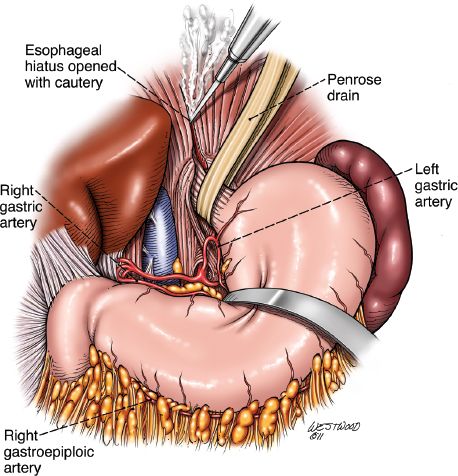

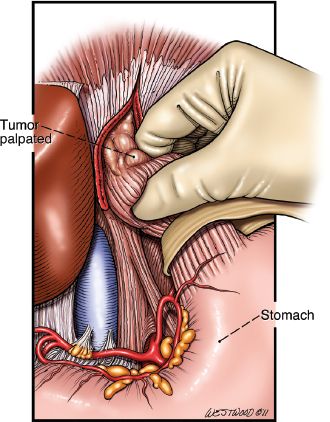

The procedure is performed through an upper midline incision (Fig. 20.2). The falciform ligament is divided. The upper hand retractor is put into place (Fig. 20.3). Assessment of the liver, hiatus, and peritoneal cavity is performed to determine resectability. The triangular ligament is divided and the liver is retracted laterally. Our dissection begins at the pars flaccida where gastrohepatic attachments and lesser omentum are taken down as we proceed superiorly on the lesser curve. These attachments are taken down sharply with electrocautery or the Ligasure Impact device (Valley Lab, Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts). The right gastric artery is preserved as the dissection is continued along the lesser curve. The right crus is dissected. The left crus and the angle of His are mobilized with electrocautery. The hiatus is opened (Fig. 20.4) and the tumor palpated in the mediastinum to ensure mobility and hence respectability (Fig. 20.5).

Figure 20.1 Figure 20.1 Patient positioned supine with head toward the right and a gel pad between the shoulders. (© 2014 Wm. B. Westwood, CMI.)

The lower esophagus including the periesophageal fat, nodes, and vagus nerves are encircled with a Penrose drain. At this point, the course of the right gastroepiploic artery is identified from the pyloroduodenal area to the middle of the greater curvature, where it generally terminates as it enters the stomach or divides into smaller branches that anastomose with the left gastroepiploic artery. This vessel will serve as the main blood supply of the gastric conduit.

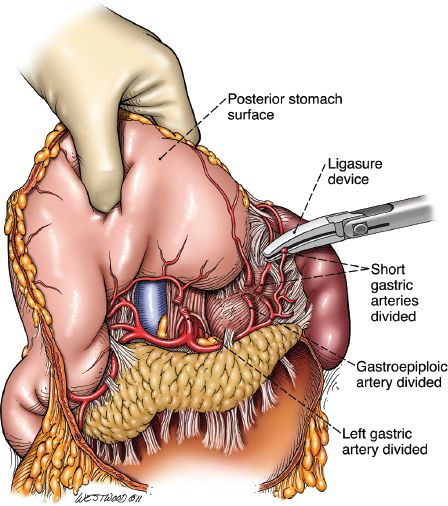

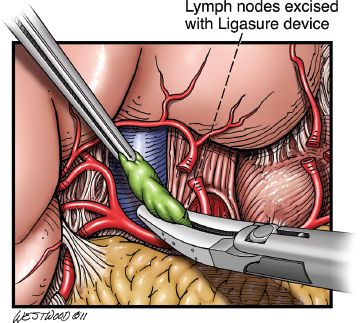

Starting at the esophagogastric junction proceeding inferiorly on the greater curve, the left gastroepiploic and short gastric vessels are ligated with the Ligasure. As the dissection proceeds down the greater curvature and the omentum is separated from the stomach, care is taken to apply the Ligasure device at least 2 cm below the right gastroepiploic artery. Dissection proceeds down to the pylorus. With gentle upward traction of the stomach, the filmy posterior attachments on the stomach are sharply divided. The left gastric artery is identified and transected at its origin usually with a linear vascular stapler. Lymphadenectomy at the celiac axis at this point is also performed (Figs. 20.6 and 20.7).

Figure 20.2 Upper midline incision is depicted. (© 2014 Wm. B. Westwood, CMI.)

Figure 20.3 A self-retaining tablemounted upper abdominal retractor (upper hand retractor, J. Hugh Knight Instrument Co., Slidell, Louisiana) is used to facilitate exposure of the upper abdomen and hiatus. (© 2014 Wm. B. Westwood, CMI.)

Figure 20.4 The hiatus is opened with cautery, and arterial blood supply to the conduit is reviewed. (© 2014 Wm. B. Westwood, CMI.)

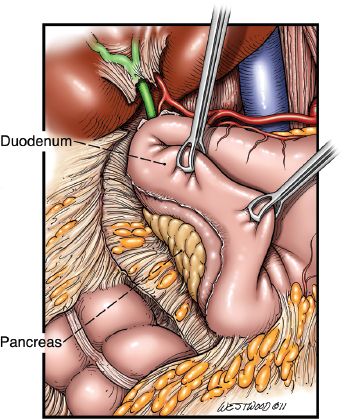

Figure 20.5 Tumor is palpated to ensure resectability. (© 2014 Wm. B. Westwood, CMI.)

Figure 20.6 Short gastric arteries divided by the Ligasure Impact device (Valley Lab, Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts). (© 2014 Wm. B. Westwood, CMI.)

Figure 20.7 Celiac lymph nodes are excised with the Ligasure Impact device (Valley Lab, Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts). (© 2014 Wm. B. Westwood, CMI.)

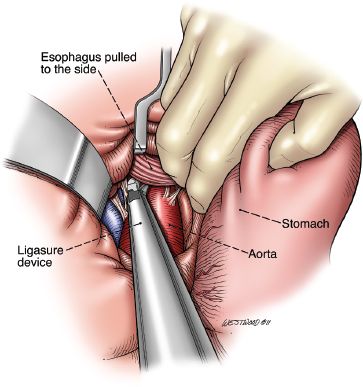

The mobility of the esophageal tumor is once again assessed to ensure that it is not fixed to the prevertebral fascia, aorta, or surrounding mediastinal structures. The diaphragm is incised up to the pericardium to open the hiatus. Retractors can be placed into the hiatus to allow ligation of the periesophageal tissues to the level of the carina under direct vision. The value of the Ligasure for this part of the procedure cannot be overstated. At least 10 cm of the distal esophagus can be mobilized under direct vision. For this maneuver to be effective, the esophagus should be retracted from one side to the other in the lower mediastinum to create tension on the tissues on the opposite side and facilitate their division (Fig. 20.8). Then, with downward traction on the esophagus, the surgeon’s hand is inserted into the hiatus and further blunt, gentle mobilization of the esophagus, to at least the level of the carina, is carried out. Mobility of the esophagus within the posterior mediastinum is assessed. If the esophagus is not fixed and transhiatal resection is possible, the mediastinal dissection is completed for now. Throughout the gastric and esophageal mobilization process, the utmost care in handling the stomach is required.

Figure 20.8 Division of the periesophageal attachments are divided with the Ligasure Impact device (Valley Lab, Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts). (© 2014 Wm. B. Westwood, CMI.)

Figure 20.9 A Kocher maneuver is depicted. (© 2014 Wm. B. Westwood, CMI.)

After gastric mobilization has been completed, a generous Kocher maneuver is performed (Fig. 20.9) to allow mobilization of the pylorus to the level of the hiatus. A 20-French jejunostomy tube is placed before proceeding with the cervical phase. This is usually placed 40 to 45 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz in a Stamm fashion.

Cervical Phase

An oblique incision is made along the anterior border of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 20.10). The incision is centered on the cricoid cartilage and extends inferiorly to the suprasternal notch. Dissection is taken down medially to the carotid sheath. The omohyoid muscle is divided. Two Gelpi retractors are placed for soft tissue retraction. The middle thyroid vein and the inferior thyroid artery are ligated. The recurrent laryngeal nerve is identified and protected. At no time should metal come into contact with the recurrent laryngeal nerve (Fig. 20.11).

Figure 20.10 A neck incision is made anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. (© 2014 Wm. B. Westwood, CMI.)