practice to utilize preoperative mesenteric angiography to evaluate the blood supply of the colon unless there is a history of mesenteric vascular disease or possible interruption of the inferior mesenteric artery in a prior abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Abstinence from cigarette smoking for a minimum of 3 weeks before the operation is an absolute requirement of the author, even in those with cancer. Those suspected of continued smoking have a urine cotinine level determined, and if recent tobacco use is confirmed, the operation is cancelled. Patients are issued an incentive spirometer at the initial consultation and are requested to use it on a set schedule throughout the day until they are admitted for their operation. They are instructed to walk 3 miles a day to condition themselves for early postoperative ambulation. The importance of this “surgeon-patient contract” is emphasized. With severe esophageal obstruction and inability to obtain adequate fluid and caloric intake by mouth, a nasogastric feeding tube is placed into the stomach, if necessary with fluoroscopic control, and tube feedings for home use are initiated. Every effort is made to avoid a hospitalization and the need for intravenous hyperalimentation before surgery, and patients are typically admitted for the esophagectomy on the day of the scheduled procedure. A mechanical cleansing of the large bowel is undertaken in those in whom there is concern about the suitability of the stomach as an adequate esophageal replacement.

Table 17.1 Indications for Transhiatal Esophagectomy (2007 Patients) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

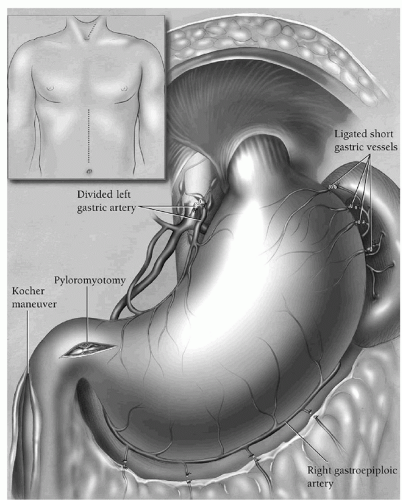

SURGICAL TECHNIQUEpyloromyotomy, and finally feeding jejunostomy. Through an upper midline supraumbilical incision (Fig. 17.1, inset), the abdomen is explored, the triangular ligament of the liver divided with electrocautery, and the left lobe of the liver retracted to the right with a liver blade retractor secured to the upper-hand supporting bar. A standard upper-hand abdominal wall retractor secured to the bar is used to retract the left side of the abdominal wall. The high greater curvature of the stomach is localized, and the adjacent greater omentum retracted to the left. A “clear space” between the omentum and the gastric wall is developed until the lesser peritoneal sac is entered. An index finger passed into this opening behind the greater omentum elevates the omentum away from the stomach and is used to define the high short gastric vessels and left gastroepiploic arcade. These vessels are sequentially clamped with 13-inch long right-angle clamps, divided, and tied with 2-0 silk, taking care to stay well away from the stomach to avoid ischemic necrosis. The gastric wall must be handled gently throughout this mobilization and unnecessary traction on the stomach avoided. Care must also be taken to avoid excessive downward traction on the high greater omentum that may be adherent to the spleen and result in a splenic capsular tear. Before dividing all of the high short gastric vessels, the direction of the dissection is changed, and the remaining left gastroepiploic vessels sequentially identified, clamped, divided, and ligated moving along the greater curvature toward the pylorus. The right gastroepiploic artery is identified by palpation and vision as it either terminates in the gastric wall or communicates through fine vessels with the left gastroepiploic arcade. The greater omentum is divided 1.5 to 2 cm inferior to the right gastroepiploic artery, carefully preserving it and repeatedly monitoring for the presence of a pulse before dividing and ligating each branch. The greater omentum is separated from the stomach to the level of the pylorus. Once this portion of the distal stomach has been mobilized, it can be better retracted to the right exposing the highest short gastric vessels still to be divided. The peritoneum overlying the hiatus is incised and the esophagogastric junction identified. The author no longer encircles the esophagogastric junction with a Penrose drain in order to minimize the chance of a traction injury to the upper stomach. The stomach is elevated and any adhesions between the retroperitoneum and posterior gastric wall divided with electrocautery.

motion of the fingers so that a narrow heart-shaped retractor can be inserted and upward traction on it exerted. This exposes the distal esophagus in the posterior mediastinum. If tumor at the cardia is adherent to the diaphragm, a rim of diaphragm may need to the resected with the specimen to achieve an adequate margin. The posterior aspect of the esophagus is gently mobilized away from the spine by two, three, and then four fingers inserted into the hiatus behind the esophagus. Using a long 13-inch right-angle clamp and a long electrocautery tip, the posterior mediastinal paraesophageal soft tissues are elevated and divided. Visible paraesophageal lymph nodes are resected. The dissection alternates from one side to the other of the esophagus moving progressively toward the carina. If either lung is seen in the field, the mediastinal pleura on that side has been violated, and a chest tube will be required later. Inserting a hand into the low mediastinum and gently “rocking” the esophagus from side to side allows assessment of the degree of fixation between the esophagus and contiguous structures, particularly the spine, prevertebral fascia, and descending thoracic aorta, which could complicate transhiatal esophageal mobilization. During this low esophageal dissection, blood pressure as recorded through the radial artery catheter is carefully watched to avoid prolonged hypotension resulting from cardiac displacement by the hand inserted into the mediastinum. After mobilizing approximately 10 cm of the distal esophagus, the low posterior mediastinum is packed with a large abdominal pad to facilitate hemostasis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree