Table 18.1 Indications for Esophagectomy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 18.2 Transthoracic Resections | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

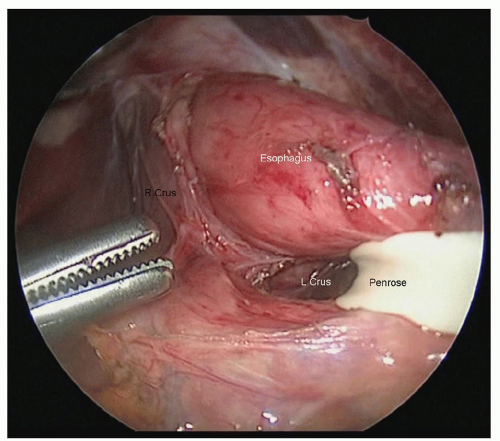

the esophagus. The phrenoesophageal membrane should be taken down, and all tissue adjacent to the esophagus should be kept with the esophagus. The crural decussation should be dissected posteriorly, and the left crus should be identified from the right side of the abdomen (Fig. 18.5). The posterior esophageal window should be developed, and all tissues adjacent to the esophagus should be dissected away from the right and left crura. After dissecting in the cranial direction toward the mediastinum, the gastrohepatic ligament should be mobilized toward the lesser curve of the stomach. An appropriately sized hiatus for conduit passage is important as too large a hiatus could result in colon herniation and too tight a hiatus can result in ischemia of the conduit. It is helpful to dissect as far into the chest as is safe before closing the abdomen, as the inferior pulmonary ligament lymph nodes from both sides can be dissected from the abdominal approach. It is usually possible to reach up to the inferior pulmonary vein, depending on patient anatomy.

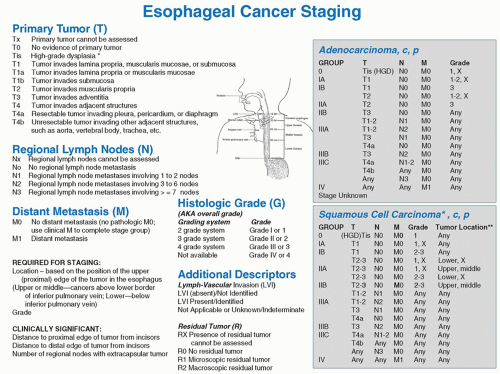

Fig. 18.2. Seventh edition of the AJCC cancer staging system. (From Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th ed. Springer; 2009.) |

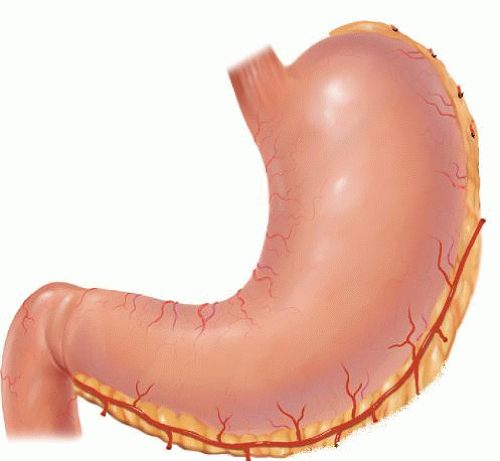

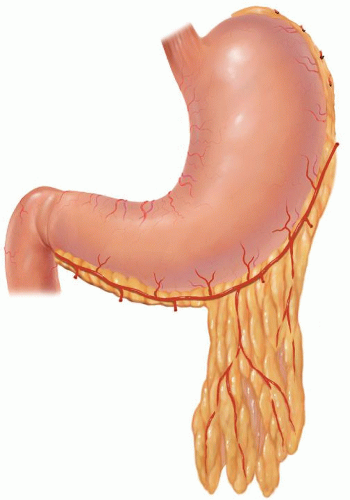

sac is entered (see Fig. 18.6, “gastroepiploic artery preservation and omental dissection”). Instead of sparing a small segment of omentum, a larger omental flap can be created to be delivered into the chest to cover the anastomosis (Fig. 18.7). When manipulating the stomach, care should be taken to avoid injury when grasping and the right gastroepiploic artery should be avoided. The division should be completed along the entire greater curve of the stomach up to where the short gastric vessels are encountered. Exposure of the short gastric vessels is enhanced by grasping the posterior aspect of the stomach and rolling the tissue toward the liver and up away from the aorta. The short gastric vessels should be divided with an energy device up to the left crus of the diaphragm. The posterior attachments of the stomach to the pancreas should be divided. The cardia of the stomach should be dissected away from the left crus. The posterior esophageal window should be created, and a Penrose drain placed around the esophagogastric junction. This drain can later be recaptured and pulled into the chest to assist in mobilizing the intrathoracic esophagus. The posterior aspect of the stomach should be dissected away from the pancreas, preserving the right gastric artery. For benign disease, the modification does not typically require a complete esophagectomy or lymphadenectomy.

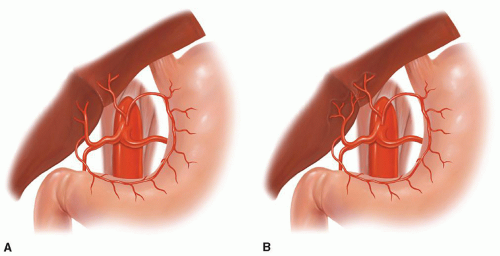

Fig. 18.8. Aberrant celiac, left gastric, or hepatic artery anatomy. (A) Replaced left hepatic artery and (B

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|