Transcervical Thymectomy

Larry R. Kaiser

INTRODUCTION

With so much emphasis today being placed on new minimally invasive techniques, it is easy to forget that some minimally invasive procedures have been around for years but seemingly never referred to as such. In a sense, one can make a strong case that transhiatal esophagectomy is a minimally invasive operation since it avoids a chest incision and we have been doing that procedure for many years, thanks to Mark Orringer popularizing it back in the 1970s. Other procedures have been “minimized” with smaller incisions, muscle sparing, and, of course, with the use of endoscopes.

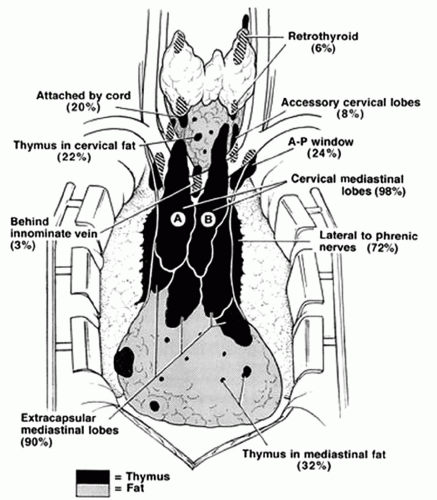

Removal of the nontumorous thymus gland for myasthenia gravis classically involved a median sternotomy and despite the efforts of some to utilize a so-called mini sternotomy, at least a portion of the sternum is still split. Jaretski in New York described even a more “maximal” approach utilizing a neck incision combined with a sternotomy making the case that aberrant “rests” of thymus occurred in locations that even a standard sternotomy might miss (Fig. 14.1). It occurred at least to a few surgeons that performing a sternotomy to remove a normal thymus gland was overkill. Working in the same city, Papatestas resurrected the transcervical approach to thymectomy during the 1970s and 1980s with results, relative to myasthenic symptoms, similar to those obtained via the much larger and more morbid operation. Cooper made a major modification to the transcervical approach by designing a retractor that instead of strictly relying on blind blunt dissection, as practiced by Papatestas, allowed for direct visualization of the anterior mediastinum to assure that all of the thymus gland was removed. Both pleural reflections could be visualized; the inferior extent of the gland and the extension of the gland into the aortopulmonary window could also be directly visualized. The Cooper thymectomy retractor allowed for an extended transcervical thymectomy, an approach more predictable and reliable.

Recognizing that a median sternotomy is a big operation with significant attendant morbidity simply to remove a normal structure that easily dissects away from surrounding structures with blunt dissection further made the case for transcervical thymectomy. However, there remained a significant group of vocal opponents to the procedure based on their contention that a transcervical approach failed to remove the entire thymus gland and certainly would miss rest of the gland that, according to Jaretski, commonly occurred in aberrant locations. The objection fundamentally was based on the contention that complete removal of the entire thymus gland was absolutely necessary if one was to achieve a complete remission of myasthenic symptoms. Whether or not that contention is valid still remains an open question. This has been further called into question since in at least one study it has been shown that in patients with ectopic thymic rests, even when removed, the incidence of complete remission remains significantly inferior to that seen in those who do not have ectopic gland. Thus, in a setting in which no procedure results in 100% remission rates, we need to look critically at the type of operation and specifically at the risk-benefit ratio involved in removing what is essentially a normal structure. It has been our hypothesis that transcervical thymectomy should be the preferred approach for the removal of the thymus gland in patients with myasthenia gravis. We believe that the risk-benefit ratio is favorable enough to make the case that essentially all patients with myasthenia should be offered thymectomy via this approach. Even those neurologists who are concerned about subjecting their patients to a surgical procedure often are swayed when they are informed about the minimally invasive nature of this procedure and the results when compared with the open procedure.

DESCRIPTION OF THE PROCEDURE

No specific preoperative preparation is required prior to proceeding with transcervical thymectomy. As opposed to thymectomy via the standard sternotomy approach, plasmapheresis is not necessary even for those patients with significant symptoms. It has been our practice to allow the attending neurologist to decide whether plasmapheresis should be done and if they wish to proceed the exchanges should be done the week prior to the planned operative procedure. We have patients take their usual medication on the morning of the operative procedure, specifically their anticholinesterase inhibitor and, if still taking it, the corticosteroid. We attempt to wean patients to no more than 10 or at most 20 mg of prednisone prior to operation.

The patient is positioned supine with an inflatable bag behind the shoulders which, when inflated, allows for maximal hyperextension of the neck (Fig. 14.2). In the office during the preoperative evaluation, we assess the degree of neck extension recognizing that in those patients with limitation to extension the procedure is somewhat more difficult with respect to visualization. The skin overlying the neck and chest is prepared in the usual manner and the appropriate draping is carried out. A small transverse incision is made as low as possible in the midline of the neck at the level of the sternal notch and carried down through the subcutaneous tissue and through the platysma down to the level of the strap muscles. It has been my preference to make this incision with a scalpel as opposed to using an energy device. Once the strap muscles are visualized, the midline raphe is identified and incised using the scissors. The midline is opened superiorly as high as possible and inferiorly down to the level of the sternal notch. The ligament traversing the sternal notch is incised with the electrocautery. The sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles on one side are grasped by the assistant and again

using the scissors dissection is carried closely along the posterior border of the sternothyroid muscle reflecting the muscle carefully away from the underlying tissue, which will be the capsule of the thymus gland. The gland has a definite salmon pink color that easily differentiates it from the surrounding cervical fat and in addition the capsule defines the gland as a separate structure. The gland is followed superiorly to its proximal extent where a small arterial branch will be encountered. A clip is placed and the gland elevated anteriorly while dissecting it away from surrounding structures both medially and laterally. A silk tie is placed at the superior most aspect of the pole of the gland to be used as a “handle” to elevate the gland and apply countertraction (Fig. 14.3). The gland is followed inferiorly to where it intersects with the opposite lobe. As described above, the opposite lobe is reflected away from the strap muscles, followed to its termination superiorly and then dissected away from the surrounding structures moving inferiorly.

using the scissors dissection is carried closely along the posterior border of the sternothyroid muscle reflecting the muscle carefully away from the underlying tissue, which will be the capsule of the thymus gland. The gland has a definite salmon pink color that easily differentiates it from the surrounding cervical fat and in addition the capsule defines the gland as a separate structure. The gland is followed superiorly to its proximal extent where a small arterial branch will be encountered. A clip is placed and the gland elevated anteriorly while dissecting it away from surrounding structures both medially and laterally. A silk tie is placed at the superior most aspect of the pole of the gland to be used as a “handle” to elevate the gland and apply countertraction (Fig. 14.3). The gland is followed inferiorly to where it intersects with the opposite lobe. As described above, the opposite lobe is reflected away from the strap muscles, followed to its termination superiorly and then dissected away from the surrounding structures moving inferiorly.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|