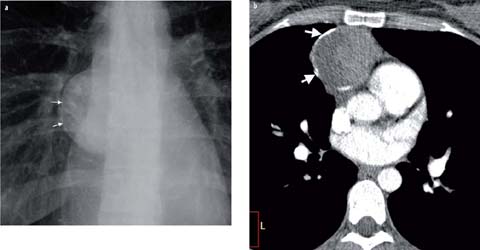

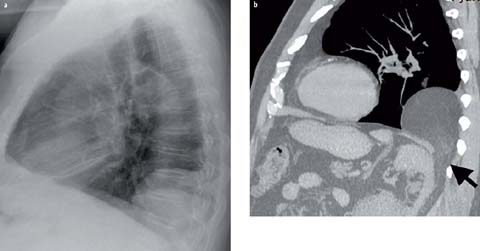

Fig 1 a, b.

Teratoma. Posteroanterior chest X-ray shows a left anterior mediastinal mass (a). Axial CT demonstrates a large soft-tissue mass with a fat component (b, arrow)

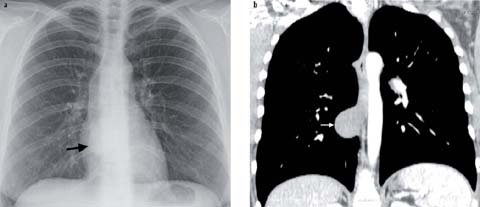

The incidence of calcification in thymomas varies from 10% to 40%. Circular peripheral calcification may occur in solid thymomas, simulating a cyst (Fig. 2). Teratomas contain calcium in about 35% of cases. Untreated lymphomas do not calcify and about 5% of them show calcifications after radiation therapy.

Fig 2 a, b.

Thymoma. Peripheral calcification is visible in the chest radiograph (a, arrows), confirmed with CT (b, arrows)

Vascular or hyperenhancing lesions may present within the anterior mediastinum. Occasionally, coronary or bypass aneurysms can simulate an anterior mediastinal mass. The key is to think about this potential, especially when a patient with median sternotomy wires presents for imaging.

Middle Mediastinum

Most middle mediastinal masses represent lymphadenopathy, foregut duplication cysts, vascular lesion, or esophageal processes. They usually present with right paratracheal widening on a frontal chest radiograph or, occasionally, the doughnut sign on a lateral examination. As with anterior mediastinal conditions, an assessment of attenuation or intensity can be helpful.

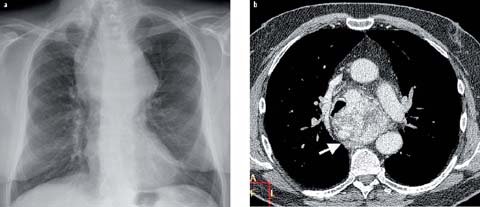

If the mass is fluid in character, the middle mediastinal mass most likely represents a foregut duplication cyst (either bronchogenic or esophageal). These cysts occasionally are higher in attenuation as a result of infection or hemorrhage (Fig. 3) and may even contain a fluid-calcium level from the milk of calcium. The risk of malignancy in these conditions tends to be low. As with anterior mediastinal lesions, the ratio of soft tissue to fluid needs to be considered. A foregut duplication cyst should have no soft tissue, enhancing element. If soft tissue is encountered, one must consider a potentially more significant process, usually low-attenuating lymphadenopathy. Such low-attenuating lymph nodes may be encountered in lung cancer, mucinous neoplasms, and mycobacterial disease.

Fig 3 a, b.

Asymptomatic bronchogenic cyst. The cyst was discovered on the chest radiograph (a, arrow) and confirmed with CT (b, arrow). Note the high attenuation, similar to that of the soft tissue

Unlike the anterior mediastinum, fat in a middle mediastinal lesion cannot be considered benign. Although esophageal or tracheal lipomas and esophageal fibrovascular polyps contain fat, so may mediastinal liposarcomas. These rare lesions may insinuate through the mediastinum and often have a predilection for the middle mediastinum.

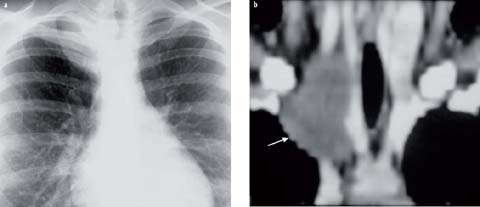

Hypervascular lesions in the middle mediastinum are most often hypervascular lymph nodes and intrathoracic extension of a goiter (Fig. 4). These hypervascular nodes (defined as higher in attenuation than skeletal muscle) may be seen with melanoma, plasmacytoma, Castleman’s disease, Kaposi sarcoma, sarcomas, and thyroid and renal cell cancers. When the high attenuating structure is tubular, a vessel must be considered. Aortic arch anomalies and azygos vein enlargement often present as a middle mediastinal mass on radiography.

Fig 4 a, b.

Large endothoracic goiter. There is with marked tracheal displacement in the chest radiograph (a). Axial CT shows marked contrast enhancement of the thyroid tissue (b, arrow)

Most mediastinal lymphadenopathy will present in the middle mediastinum. Occasionally, these nodes will be calcified. These calcified nodes are usually indicative of an old granulomatous process, such as healed tuberculosis or histoplasmosis or sarcoidosis, but care must be taken to remember that certain tumors also tend to present with calcified mediastinal lymph nodes, including ovarian serous adenocarcinomas, mucinous colon neoplasms, and osteosarcomas.

Another potential for a perceived middle mediastinal mass on radiography will be a dilated esophagus. Although a distal mass may also result in esophageal dilatation, it is usually only achalasia that results in esophageal widening that can be seen on a chest radiograph.

Posterior Mediastinum

A vast majority of posterior mediastinal masses will be neurogenic in origin. In adults, these tend to be benign nerve sheath tumors, usually schwannomas and neurofibromas. In children and younger adults, they tend to be sympathetic ganglion in origin, such as ganglioneuroblastoma, neuroblastoma, or ganglioneuroma. The key in separating the two groups is to assess the overall shape, comparing the z-axis to the xy-axis. Nerve sheath tumors tend to be spherical (equal in all 3 axes), while the ganglion lesions are longer in the z-axis and are more cylindrical. Osseous lesions represent the second most common group of posterior mediastinal disease. Although metastases are often considered, one cannot forget about diskitis/osteomyelitis. This latter condition can present as insidious back pain and can easily be overlooked.

As with the other compartments, attenuation or intensity can be helpful. On CT, a potential pitfall is that myelin-rich neurogenic lesions may look cystic (Fig. 5). For this reason, with posterior mediastinal lesions we often rely on MR imaging. True posterior mediastinal cystic lesions are rare. Although neuroenteric cysts exist, they are often associated with vertebral anomalies and rarely encountered de novo in adults. Instead, a cystic lesion in the posterior mediastinum is much more likely to represent a lateral meningocele or post-traumatic nerve root avulsion.

Fig 5 a, b.

Ganglioneuroma. The lesion, visible as a mass in the right apex (a), was confirmed with enhanced CT (b, arrow). Note the low CT density, which may create confusion with a cystic mass

Fatty lesions are unusual in the posterior mediastinum but when encountered may invoke extramedullary hematopoiesis. While rare, in patients with anemia, extramedullary hematopoiesis may develop in the posterior mediastinum. The etiology of this condition remains unknown. Some authors have postulated that it develops from extruded marrow while others have suggested that it develops from totipotent cells in the paravertebral space. When the patient is anemic, extramedullary hematopoiesis will present with bilateral masses that enhance similar to spleen without a connecting bridge. As the patient returns to normal hematocrit, the yellow marrow will take over. The net effect is bilateral posterior mediastinal fatty masses. In the elderly, Bochdalek hernias should be included in the differential diagnosis (Fig. 6).

Fig 6 a, b.

Bochdalek hernia. Lateral chest radiograph shows a large posterior mediastinal mass (a). Sagittal CT demonstrates abdominal fat herniating through a posterior diaphragmatic defect (b, arrow)

Hypervascular lesions in the posterior mediastinum are less helpful than with the other compartments. Most often these are related to an aneurysmal aorta or enlarged collateral vessels as with aortic coarctation. As described above, extramedullary hematopoiesis may be seen with bilateral hypervascular paravertebral masses.

Conditions That Disregard the Compartment Model

Certain conditions tend to disregard the compartment model of the mediastinum. Even with these lesions, understanding the attenuation or intensity can be helpful. These include infection and hematoma, which will result in fat stranding and soft tissue attenuation throughout the mediastinum, often in more than one compartment.

Lymphangiomas and hemangiomas also tend to disregard the compartment model. The former tend to be fluid in their attenuation and insinuate throughout, while the latter will be higher in attenuation.

Of course, lung cancer may present with metastases to any compartment and, unfortunately, tends to metastasize to more than one region.

Conclusion

The mediastinum represents a space that may be impacted by a large number of lesions. Having an approach based on location and characterization will allow the radiologist the ability to create a useful, targeted differential diagnosis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mediastinal masses based on location and characteristics

Mediastinal compartment | Most common | Fluid | Fat

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|