The timing of surgical intervention for fixed stroke has been relatively controversial since the introduction of carotid endarterectomy (CEA). Early on, attempts at acute intervention without the benefit of adequate cerebral imaging techniques produced results that, in retrospect, would seem predictably catastrophic. The early pioneers were operating on patients whose intracranial pathology was largely unknown and ranged from acute hemorrhagic infarcts to mass lesions, in addition to an unknown number of ischemic strokes. Wylie, Hein, and Adams reported in 1964 that of nine patients who underwent CEA in the presence of profound stroke, 55% died within 3 days. In contrast, DeBakey and colleagues reported a more optimistic experience in 1965 of a 7% mortality in 406 patients who underwent operations within 1 week of a stroke. DeBakey’s results, however, were not characteristic of most surgeons’ experiences. Rob documented a 21% mortality in a series of 91 patients in 1969, and Murphey and Maccubin reported a 43% mortality among 44 patients with stable stroke. In 1969, Blaisdell and colleagues reported a 42% mortality in their series of 50 patients operated on within 2 weeks of the event. Additional experimental data emerged that outlined the mechanism by which a bland or ischemic infarct might convert to a hemorrhagic infarct with reperfusion. These findings supported the policy advocated by most surgeons in the mid-1960s, who recommended waiting 4 to 6 weeks after an acute event for stabilization before CEA.

During the late 1970s, neurologists began to recommend cerebral arteriography earlier in the course of stroke evaluation. A patient population was thus identified with fixed deficits associated with high-grade, preocclusive lesions of the internal carotid artery (ICA). Anecdotal evidence suggested that these patients were at higher risk for recurrent stroke or extension of their infarct during the 4- to 6-week waiting period and prompted reconsideration of earlier intervention. A recurrent stroke rate of 20% was reported by Bardin and colleagues in patients who sustained a permanent neurologic deficit and prompted their recommendation that prophylactic CEA be considered in such patients with small fixed deficits. Takolander, Bergentz, and Ericsson reached a similar conclusion but continued to recommend delay of CEA beyond 4 weeks after the acute event. Evidence from the Stroke Data Bank documented recurrent stroke in 14% of patients within 2 years, 30% of which occurred within the first 4 weeks. Computed tomography (CT) evidence documented second infarctions in some 10% within 6 weeks, and the mortality rate associated with a second stroke remained 30%. The high incidence of recurrent stroke with its associated morbidity prompted a reassessment of the wisdom of waiting 4 to 6 weeks before intervention for appropriate patients with residual carotid territory at risk.

The initial experience at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital with a small group of 28 patients who had sustained an isolated fixed deficit and were operated on within a mean of 11 days following the onset of symptoms proved favorable. The duration of deficit ranged from 2 to 30 days, but 53% underwent CEA within the first week after stroke. Of the 21 patients who had a preoperative CT scan, 62% were positive for stroke. All 28 patients had a minimum of 75% stenosis of the ipsilateral ICA by arteriographic criteria, and 14 had lesions in excess of 90%. Of 18 patients for whom the contralateral carotid artery was imaged, 95% stenosis was documented in three, and three additional patients had a contralateral occlusion.

The CEA technique employed did not vary from that used for elective endarterectomy for standard indications. The procedure was carried out with general anesthesia and electroencephalographic (EEG) monitoring, with an indwelling shunt inserted on the basis of EEG criteria after carotid clamping. A patch was used at the discretion of the surgeon, and a completion arteriogram was carried out in all patients. (The study was performed before the adaption of routine completion Duplex ultrasonography.) The 30-day operative mortality consisted of one death, which resulted from pulmonary embolus. There were no new neurologic deficits, and no patient developed extension of the prior infarction. After a mean follow-up of 2 years, the 26 surviving patients sustained two new neurologic deficits: One was transient in the contralateral hemisphere, and the second proved fatal.

One of the more significant findings in this group, however, was an increased shunt requirement based on EEG criteria. In contrast to routine elective CEA, in which 18% of patients required a shunt, 40% of the group undergoing CEA for a small fixed deficit required a shunt. Of these 11 patients, three had significant contralateral stenosis and a fourth had contralateral occlusion. Thus of the six patients with either severe contralateral stenosis or occlusion, four required an indwelling shunt.

Based on our experience, we recommend prompt intervention for patients with significant carotid stenosis and residual carotid territory at risk for either recurrent stroke or extension of the original infarct. This policy was based on the premise that removing the source of emboli reduces the chance of a recurrent event and on evidence indicating that restoration of normal blood flow, and therefore oxygen delivery, minimizes the ischemic penumbra. It has been suggested that surrounding the central zone of irreversible neuronal infarction is a larger, patchy region of marginally viable tissue that, although dysfunctional, remains recoverable. This hypothesis is based on positron emission tomography scan studies, which document such marginal zones for several days after a stroke, and on magnetic resonance imaging, which shows progressive cell death in this penumbral zone for as long as a week after the initial event. There is reason to support the belief that enhanced oxygen delivery can reverse the preordained size of the penumbra and allow a higher percentage of marginal neurons to recover.

Early series supported a policy of prompt CEA after the onset of a nondisabling stroke. Similar to our experience, Rosenthal and coworkers reported a 3% combined stroke and death rate for patients operated on within 3 weeks and 5.3% after 3 weeks, all of whom received shunts. In contrast, Giordano and colleagues reported a stroke and death rate of 22% among 27 patients operated on within 5 weeks, but it is not known whether any form of cerebral protection was used. Dosick and colleagues identified 110 patients with limited fixed deficits and negative CT scans. Endarterectomy was carried out within 14 days under shunt protection without mortality and with only one posterior stroke. There were no new events in the ipsilateral carotid territory. Piotrowski and coworkers reported in 1990 that early CEA (within 6 weeks) was carried out in 82 patients, with one new stroke and one death for a combined morbidity of 2.4%. The majority of the patients (86%) received shunts.

Over time, it has become clear that the maximum benefit of CEA after a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke can occur even earlier. In 2004, the Oxford Vascular Study Group undertook a prospective study of patients presenting with TIA or minor stroke. For patients presenting with a TIA, the risks of repeat stroke after 7, 30, and 90 days were 8%, 12%, and 17%, respectively. For patients presenting with a minor stroke, the risks of stroke were 8% to 12% at 7 days and 11% to 15% at 30 days. A similar stroke risk of 8% after 30 days was obtained in a meta-analysis reviewing the risk of stroke after TIA. The ABCD2 scoring system, which includes the patient’s age, blood pressure, presenting neurologic examination, duration of TIA, and presence of diabetes mellitus, was developed specifically to identify the patients at high risk for stroke after TIAs.

Patty’s group retrospectively divided 228 patients undergoing CEA after stroke into weeks elapsed between stroke and CEA; permanent postoperative neurologic deficits occurred in 2.8%, 3.4%, 3.4%, and 2.6% of patients undergoing CEA 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks after stroke, demonstrating that the incidence of postoperative stroke was equivalent throughout the first month after stroke and acceptably low for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Only the preoperative infarct size correlated significantly with the probability of postoperative stroke; risk for permanent neurologic deficit after CEA increased by a factor of 1.73 with each 1-cm increase in preoperative diameter of infarct. Prior reports found no correlation between size of preoperative infarct and risk of stroke.

Sbariglia and colleaguges examined the risk of postoperative stroke in an even earlier period after stroke. In this prospective multicenter Italian study of 96 patients in which the mean time elapsing between the onset of stroke and endarterectomy was 1.5±2 days, 3% of patients experienced a worsening neurologic deficit postoperatively, 9% had no improvement in neurologic status, 39% were asymptomatic, and 47% demonstrated improvement in neurologic status. According to Ranter and coworkers, most of the new strokes that occurred in patients awaiting CEA occurred 3 to 4 weeks after the initial event.

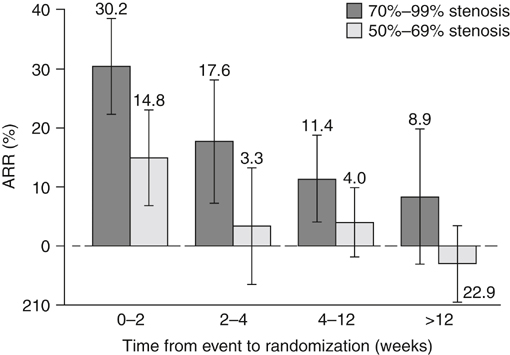

The Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists Collaboration (CETC) combined data from 5900 patients enrolled in the European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST) and North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET). They observed that the benefit of CEA was greater in men than in women and in patients older than 75 years and that it was greatest in patients randomized within 2 weeks of their last event (with a subsequent mean 7-day delay until surgery) ( Figure 1 ). The absolute risk reduction during this time period was 30.2% in patients with 70% to 99% stenosis and 14.8% in patients with 50% to 69% stenosis. There was a gradual decrement in benefit of CEA until 12 weeks after the initial event, at which point there was no benefit to surgery, which the authors surmised was a result of healing of the unstable atheromatous plaque or an increase in collateral blood flow to the symptomatic hemisphere.

Only gold members can continue reading.

Log In or

Register to continue

Related

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Join