Am I going deaf, or are hearts not as noisy as they used to be? I’ve had my hearing tested, just some high-frequency loss (probably from that Edgar Winter concert). So I think it’s that hearts are more finely tuned than in the past. I can’t remember the last good S4, the one you could palpate. Or the rumble S3 complex or opening snap you called in the medical students to hear. Many of the wonderful sounds we heard have vanished because the diseases that spawned them have been tamed. Rheumatic heart disease, the most prolific composer of eponymous symphonies (Graham Steell, Austin Flint) has long put down the baton. Similar fates have befallen S4, the product of untreated hypertension, and S3, the result of untreated heart failure. The thrill of post–myocardial infarction ventricular septal defect was gone once it encountered streptokinase, and tuberculous pericarditis no longer knocked after streptomycin.

As a result, the importance and skill of listening to the heart has disappeared in our thinking and in our notes. A default entry for cardiac examination in our hospitals electronic medical record is “CV: RRR,S1S2” Honestly, that’s it. I mean S1S2 is pretty much a given isn’t it? The only patients I know without S1 and S2 are dead. Part of the reason we have become complacent in performing a physical examination is that no one will pay for it. Simply checking the box S1S2 satisfies the auditor and simply checking a few other boxes for other organ systems indicating that the patient indeed has a normal-shaped head and 2 legs satisfies that you have performed a “comprehensive” physical exam.

This reminds me of a shortcut we were taught on our surgery rotation: “the universal point of auscultation.” By placing your stethoscope at a single point around the xiphoid process, you could hear the heart, the lungs, and the stomach all at once and therefore speedily perform our era’s version of the “comprehensive” physical exam. On to better things that required scalpels.

There’s an App for That

So I fear that the heart’s sound is threatened by extinction like some lost tribal dialect. To make the art and science of auscultation more appealing to the current generation of students I think it would help to rekindle the discipline of phonocardiography. By using phonocardiography as the springboard, we can first “see” what the heart sounds like and then go back to the bedside to “hear” the same sounds.

I value my stethoscope highly, but if the phonocardiogram had been invented before the stethoscope, I believe the stethoscope, when it came along, would have been regarded as no more than a curiosity—a cardiac party toy—no longer carried in our jacket pockets. Even so, as we will see, if the phonocardiogram hadn’t come along when it eventually did, the use of the stethoscope might have disappeared into obscurity.

The phonocardiogram translates what we hear with our ears and feel with our hands onto a piece of paper, where it can be seen with our eyes and be far more easily measured and quantified. Heart sounds and murmurs barely cross the threshold of audibility of the human ear; we hear only a fraction of the sounds produced. Loud sounds frequently mask adjacent shorter or softer sounds. Furthermore, at best we can discriminate time differences in sound of 20 or 30 milliseconds and clinically significant components of heart sounds such as the splitting of heart sounds or timing of ejection clicks can be much narrower. The phonocardiogram overcomes these handicaps. Its allure is that it is digital, technical, visual, objective—far more science than art. And so, engineers are working on a way to be able to place your mobile phone on a patient’s chest and record a high-fidelity display of the patient’s heart sounds. If they are successful, it will revolutionize the physical exam and perhaps make auscultation obsolete. But for now, establishing the visual image of heart sounds in the clinician’s brain will allow him or her to go back to the bedside with the stethoscope and listen for and appreciate what they have already seen.

Phonocardiography and its sister science apexcardiography had a cometlike 40-year trajectory of popularity beginning roughly in 1935 then largely burning out by 1975, extinguished by the new science of echocardiography. To give some perspective on the purpose of reviving phonocardiography and adapting it to the contemporary age, I would like to revisit some of its fascinating history and, along the way, retell some amusing vignettes about cardiac auscultation. As we will see, the results of the phonocardiogram frequently allowed clinicians to go back to the bedside and hear for the first time what they had previously overlooked or misinterpreted.

The phonocardiogram apparatus was huge, like an early computer mainframe ( Figure 1 ). Replete with vacuum and oscilloscope tubes, it could fill a typical hall closet. It was throughout its earlier existence a research tool. Fastidious technique was demanded in recording: the barium titanate crystal microphones applied to the chest delicate and fragile, the patient needing to be cooperative with breath holding, the recording on photographic plates that required darkroom development. Yet many mysteries of heart sounds were solved—answers that we now presume to be obvious—only through the application of the phonocardiogram. The sequence of the heart sounds, the implication of splitting of the sounds, and the interpretation of many murmurs were all unknowns before the phonocardiogram.

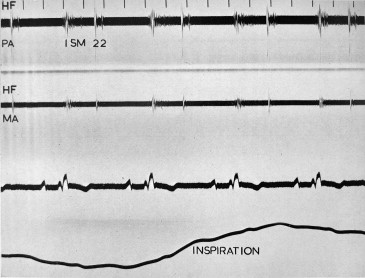

For example, that the second heart sound could be fixed in its splitting was recognized only by studying phonocardiographic recordings in Aubrey Leatham’s laboratory at the London Hospital. The superb clinicians of the day recognized atrial septal defect but despite listening to scores of hearts with this affliction, the pathognomic fixed splitting was not described until the eureka moment when Leatham’s lab technician, watching the galvanometer string wiggle, announced that the sounds were not moving with respiration, that “the split was fixed” ( Figure 2 ).

Cardiac thinking in that era was strongly influenced by the opinions of its great minds—James Mackenzie and Thomas Lewis, among a few others. As astonishing as this is to us today, they were completely dismissive of the significance of systolic murmurs. This was a belief fostered by their experience in World War I. During the Great War, so many soldiers suffered from “neurocirculatory asthenia,” or “soldier’s heart,” that the British Military Heart Hospital was established to research and treat the near epidemic of cases. Thirty-six thousand soldiers were discharged during the war as unfit for cardiac reasons, and many fold more were hospitalized, on average for 5 months at a time. This threatened to cripple the fighting force. A feature of the soldier’s heart was the presence of a systolic murmur heard at rest or after exertion, and this was used as an objective finding that could lead to discharge on medical grounds and the awarding of a lifelong pension. Lewis, lecturing after the war, discussed the significance of systolic murmurs at length, especially those produced by exertion. “They will find in these young men precisely the signs which have been used widely during the period of the war as evidences of ‘organic’ disease of the heart, which have led to so many improper rejections of recruits, to some many improper discharges from the service, and now form the basis of many unnecessary or unnecessarily high pensions.”

The great minds rebelled against the practice of labeling systolic murmurs as a source of invalidism. They responded that not only were these systolic murmurs in soldiers innocuous, but, taking it a step further, they argued that virtually all systolic murmurs were inconsequential. Mackenzie, acknowledged as the founding father of British cardiology, was frequently heard to say, when faced with a systolic murmur, that it would be better “to throw the stethoscope away.” Lewis lectured, “It is my confident belief that, had systolic murmurs and modifications of the heart sounds never been discovered, the practice of the profession would have stood on a much higher plane today than it actually does.” In fact, both Mackenzie and Lewis believed that devices such as the stethoscope, along with the electrocardiograph, were better kept out of the hands of the general practitioner. They felt the findings were often misinterpreted and detracted from the proper physical exam that was conducted by palpation. If they had their way, they would have banished the stethoscope from general use.

Thinking was so colored by rheumatic heart disease that valvular diseases producing systolic murmurs, pure aortic stenosis and mitral regurgitation, were not believed to exist independently from their rheumatic counterparts, aortic regurgitation and mitral stenosis. Lewis indicated, “To diagnose aortic stenosis in the absence of signs of incompetence is outside the province of general practice; it is for everyone a hazardous undertaking. To recognize that mitral incompetence is present, while mitral stenosis is not, is a task fraught with not inconsiderable difficulties; furthermore, when it is done, it gives little or no aid when we come to prophecy.” Lewis’s colleague, William Evans, said the diagnosis of mitral incompetence was more a description of the physician who diagnosed it ( Figure 3 ). Thus, it was in this setting, despite the forceful opinions of the great minds that Leatham, again armed with his phonocardiogram, established the character and qualities of systolic murmurs that are still recognized today. By studying the pattern of phonocardiographic recordings, he defined the “ejection” murmur, which was diamond shaped due to ejection of blood into the great vessels and ended before or with the closing sound of the respective valve ( Figure 4 ) and the “pansystolic” murmur ( Figure 4 ), rectangular shaped, beginning with the first and ending with the second heart sound of the valve affected, which he recognized was due to valvular regurgitation and which he declared could exist in isolation. Today, when we go into a patient’s room, we try to listen for the same murmur qualities and timing that he established but that were not recognized or believed to exist before the advent of phonocardiograms, even by the great auscultators of the day. And so phonocardiography rescued the stethoscope from irrelevance by defining visually and scientifically what was being heard, a role it could fulfill today as well.