and Alessandra Cancellieri2

(1)

Department of Radiology, Bellaria Hospital, Bologna, Italy

(2)

Department of Pathology, Maggiore Hospital, Bologna, Italy

Pathology | Alessandra Cancellieri Alberto Cavazza | |

Radiology | Giorgia Dalpiaz |

Introduction and anatomy | Secondary lobule | Page 28 |

Elementary lesions | Defining lesions: neoplasm Defining lesions: mixture Non-defining lesions: inflammation Non-defining lesions: fibrosis | Page 31 Page 34 Page 37 Page 38 |

How to approach the diseases | Anatomic distribution Patterns Ancillary histologic findings | Page 40 Page 45 Page 48 |

Introduction and Anatomy

Secondary Lobule

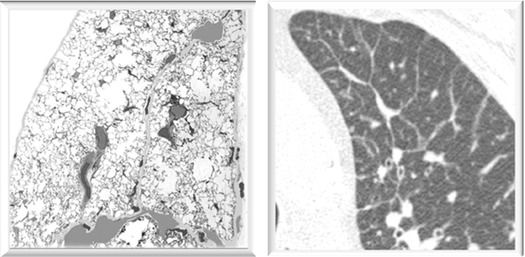

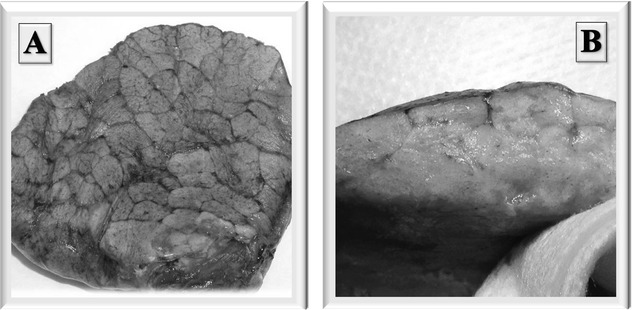

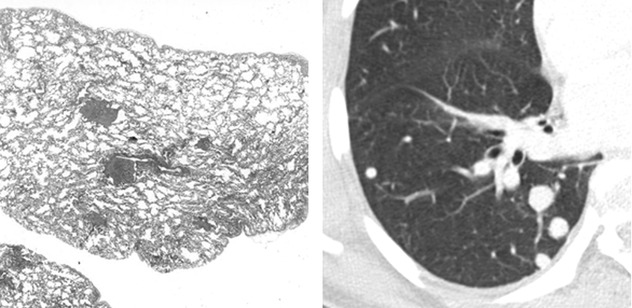

The lesions of interstitial lung diseases populate the framework of the secondary lobule. These are polygonal structures, 1–2 cm in diameter, bound by complete or incomplete connective tissue (interlobular septa), well visible on the pleural surface as thin anthracotic lines due to the deposition of pigment along the lymphatic routes.

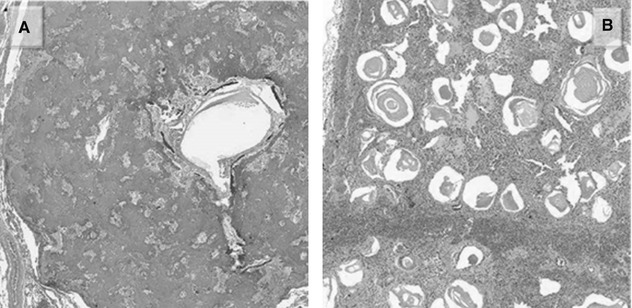

In the above figures, interlobular septa are particularly well recognizable because of the black anthracotic material along the perilobular lymphatics. Both on the pleura (A) and on the cut surface (B).

Main Components of Secondary Lobule

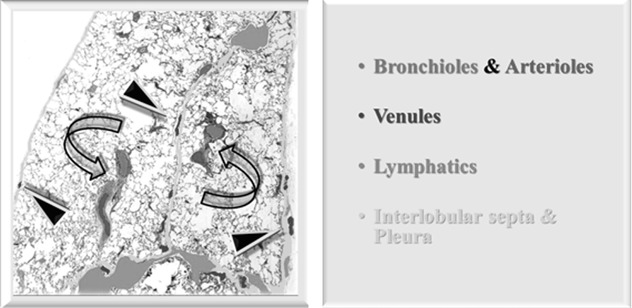

The main components of secondary lobule are:

Bronchioles and arterioles constitute the bronchovascular bundle in the center of the lobule ( ). Bronchioles and arterioles come along together following the same routes.

). Bronchioles and arterioles come along together following the same routes.

Venules, on the contrary, can be found peripherally, in the interlobular septa and along the pleura (▶).

Lymphatics, of variable caliber but usually smaller than bronchioles and arterioles, are present in all the above-mentioned compartments (i.e., bronchovascular bundle, interlobular septa, and pleura).

Rule of thumb: no matter how they are cut, bronchioles and arterioles should have approximately comparable size (and – therefore – lumen diameter) and, often, shape. When arterioles and bronchioles are of different caliber, something is abnormal.

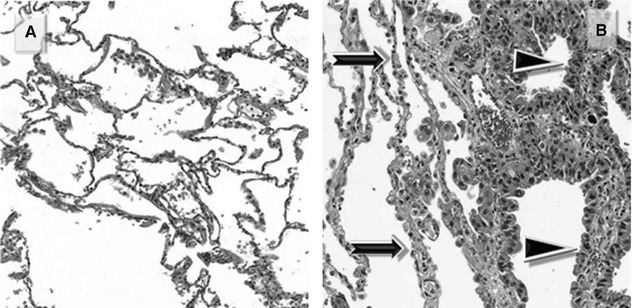

Intralobular Interstitium/Septa

Within the lobule, a fine stromal network of intralobular septa make up the framework of the acini and, more specifically, of the anatomical units responsible for gas exchange: respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, alveolar sacs, and alveoli. The intralobular (alveolar) septa contain the smallest branches of arterioles and venules, as well as the capillary network.

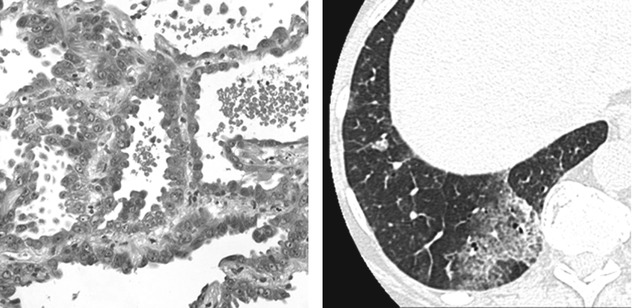

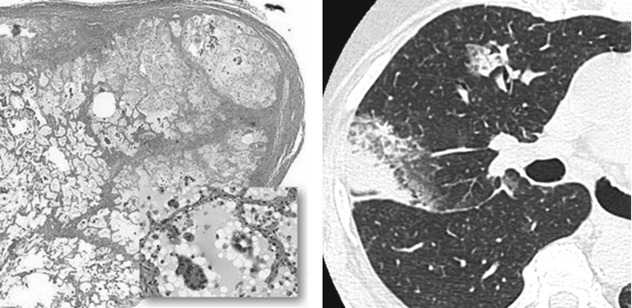

Figure A below shows normal intralobular septa. Figure B shows normal intralobular septa (➨) and thickened septa due to “lepidic growth” (▶) in a patient with adenocarcinoma.

HRCT

On HRCT, secondary lobules appear to be of various sizes and shapes, depending at least partially on the relationship of the lobule to the plane of scan. They may be thought of as having three primary components:

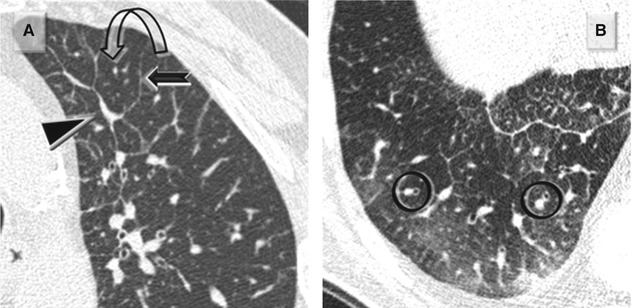

Interlobular septa and septal structures (Figure A below). At the periphery of lobule, the interlobular septa are arranged more or less regularly, parallel to each other and perpendicular to the pleural surface (➨). Venules can sometimes be seen as linear or arcuate structures (▶).

In healthy patients, a few septa are often visible in the lung periphery, but they tend to be inconspicuous; normal septa are most often seen in the apices.

Centrilobular region and centrilobular structures (Figure A and Figure B below). Centrilobular arterioles and bronchioles measure approximately 1 mm in diameter. Arterioles can always be easily resolved on HRCT ( ). Pathologic thickened bronchioles are visible close to arterioles (

). Pathologic thickened bronchioles are visible close to arterioles ( ).

).

In healthy patients, bronchioles are not visible because the wall thickness measures approximately 0.15 mm; this is at the lower limit of thin-section CT resolution.

Intralobular interstitium (lobular parenchyma). Within the lobule, a fine stromal network of intralobular septa make up the framework of the acini and, more specifically, of the anatomical units responsible for gas exchange: respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, alveolar sacs, and alveoli. The intralobular septa contain the capillary network which connects the arterial and venous system.

In healthy patients, the intralobular interstitium is only partly visible on CT: the most peripheral millimeters of the subpleural lung are homogeneously black.

Colby TV, Swensen SJ (1996) Anatomic distribution and histopathologic patterns in diffuse lung disease: correlation with HRCT. J Thorac Imaging 11(1):1

Webb WR (2006) Thin-section CT of the secondary pulmonary lobule: anatomy and the image – the 2004 Fleischner lecture. Radiology 239(2):322

Elementary lesions

Elementary lesions of the lung can be separated into two groups:

Defining lesions: lesions which are per se explanatory, regardless of their topography within the secondary lobule (neoplasms and mixture)

Non-defining lesions: lesions which are similar almost everywhere, their peculiarity being mainly due to their topography (inflammation and fibrosis)

Defining Lesions: Neoplasm

A systematic description of the histological and cytological features of the single lesions is beyond the aim of this atlas. All the possible histotypes can be involved, namely, epithelial, lymphoid, and mesenchymal. According to the modality of growth of the neoplastic cells, several presentations may be identified.

Multiple Neoplastic Nodules

As a rule of thumb, neoplastic lesions in the lung are similar to malignancies elsewhere, that is, they present as solitary or multiple discrete nodules. Metastases often have random distribution and different size. Please also refer to hematogenous metastases in the chapter “Nodula Diseases”.

Interstitial Neoplastic Thickening

This modality of growth along the bronchovascular bundles, in the interlobular septa, and within the pleura is called carcinomatous lymphangitis (CL). Please also refer to carcinomatous lymphangitis in the chapter “Septal Diseases”.

Lepidic Growth

A peculiar pattern of presentation frequently responsible for the so-called ground-glass opacity (GGO) in CT is due to a lepidic growth of the neoplasm along alveolar septa. Please also refer to Adenocarcinoma in the chapter “Alveolar Diseases”.

Partial or Complete Neoplastic Alveolar Filling

In the context of a malignancy, this can be due to the presence of mucus as in pneumonia-like pattern of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma, formerly mucinous BAC, or to the presence of neoplastic cells. In these cases, ground-glass opacity (GGO) and consolidations are the radiological expression of the disease, and more often a mixed pattern, where the two aspects coexist, is present. Please also refer to Adenocarcinoma in the chapter “Alveolar Diseases”.

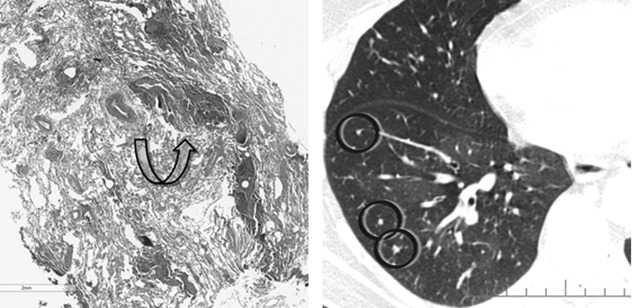

Peribronchial and Peribronchiolar Neoplastic Growth

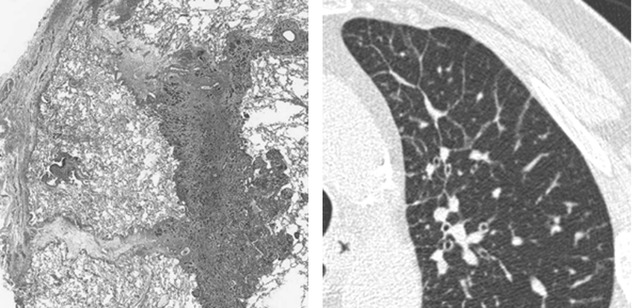

Some tumors preferentially grow along bronchial and bronchiolar walls eventually invading their lumen. Also, preinvasive conditions such as DIPNECH (diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia) can exhibit this pattern of growth ( ). Expiratory HRCT shows patchy areas of black and white aspect due to air trapping. Some small solid nodules, consisting of tumorlets or typical carcinoids, also coexist (

). Expiratory HRCT shows patchy areas of black and white aspect due to air trapping. Some small solid nodules, consisting of tumorlets or typical carcinoids, also coexist ( ). Please also refer to DIPNECH in the chapter “Dark Lung Diseases”.

). Please also refer to DIPNECH in the chapter “Dark Lung Diseases”.

). Expiratory HRCT shows patchy areas of black and white aspect due to air trapping. Some small solid nodules, consisting of tumorlets or typical carcinoids, also coexist (

). Expiratory HRCT shows patchy areas of black and white aspect due to air trapping. Some small solid nodules, consisting of tumorlets or typical carcinoids, also coexist ( ). Please also refer to DIPNECH in the chapter “Dark Lung Diseases”.

). Please also refer to DIPNECH in the chapter “Dark Lung Diseases”.

Engeler CE (1993) Ground-glass opacity of the lung parenchyma: a guide to analysis with high-resolution CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 160(2):249

Davies SJ (2007) Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: an under-recognized spectrum of disease. Thorax 62(3):248

Defining Lesions: Mixture

Miscellaneous elementary lesions that can be encountered in the presence of a diffuse lung disease are (among the others) the following:

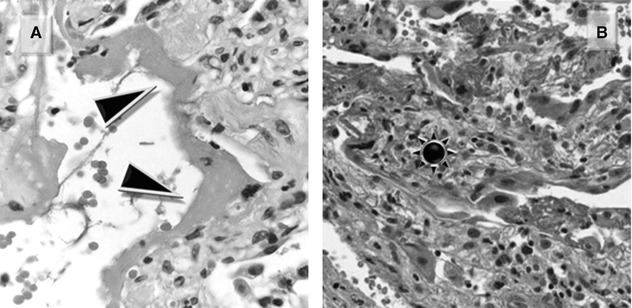

Hyaline Membranes

Characteristic of the exudative phase of a diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), they consist of proteinaceous exudate which adheres to the inner surface of the alveoli (Figure A ▶).

During the subsequent proliferative phase, the membranes are incorporated within the alveolar septa, which become thick (Figure B  ).

).

).

).

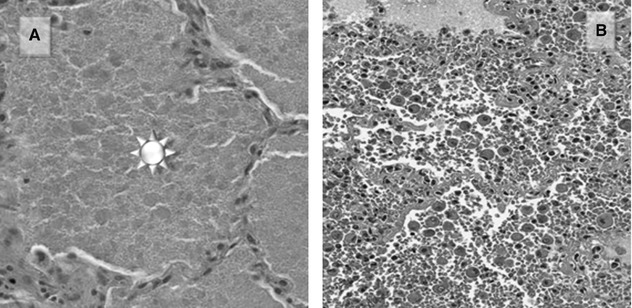

Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis (PAP)

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) consists of amorphous, lipid-rich, eosinophilic material with small globules and cholesterol clefts, within the alveolar spaces, with a rim of retraction at the edge (Figure A  ).

).

).

).Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage (DAH)

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) is characterized by fibrin and hemosiderin-laden macrophages, which can be appreciated both on cytology in BAL fluid and at histology (Figure B). Capillaritis is often part of the picture; nevertheless, it represents a transient phenomenon and therefore it is not constantly seen.

Amyloid

Amyloid, whether nodular or interstitial, isolated finding or associated to chronic inflammation or low-grade lymphomas consists of the deposition of a homogeneous, acellular, pink material which can calcify or ossify (Figure A).

Microlitiasis

Microlitiasis appears as tiny, calcified micronodules filling the alveolar spaces (Figure B).

LAM

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is characterized by the presence of cysts with thin wall containing smooth muscle bundles (Figure A). LAM cells are spindle shaped and plump, with vacuolated cytoplasm.

Necrosis

Necrosis refers to the premature death of cells in living tissues; this is a detrimental event as opposed to apoptosis, which is actually the programmed cell death. It mostly appears as amorphous material with or without inflammatory cells (Figure B). Histologically, viable tissue cells and lung architecture (including vessels) are no longer appreciable in any kind of necrosis; so, the necrotic portion of a process results avascular in a computed tomography performed after the administration of contrast medium. Cavitation of the necrotic areas is also possible and frequent.

Coagulative necrosis is characteristic of hypoxic conditions, such as infarction. It consists of homogeneous, eosinophilic material almost devoid of inflammatory cells. Ghost images of the necrotic structures are often identifiable.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree