Chapter 33 Thrombolysis for Arterial and Graft Occlusions

Technique and Results

History

The fluidity of blood post mortem is an observation that dates to the Hippocratic school in the fourth century bc.1 Almost 2000 years later, it was rediscovered by the Italian anatomist Malpighi.2 In 1761, Morgagni noted that blood does not retain its liquid state after death but frequently forms clots.3 This is followed by partial or complete reliquefaction.

In 1906, Morawitz observed that postmortem blood destroys fibrinogen and fibrin in normal blood.4 Thus, the presence of an active fibrinolysin was postulated. The term fibrinolysis had been coined by Dastre in 1893 to describe the disappearance of fibrin in unclottable blood obtained from dogs subjected to repeated hemorrhage.5 From the latter part of the nineteenth century until the present, intense investigation has been undertaken to elucidate the complex and vital functions of the fibrinolytic system. The role of the fibrinolytic system from a homeostatic point of view is fully appreciated. The interplay of components, activators, and inhibitors are becoming more appreciated. The potential to harness the fibrinolytic system for therapeutic means has emerged in the last few decades, and results from prospective clinical trials are now available, providing guidelines to patient selection and therapy. For the vascular specialist, thrombolytic therapy represents one of the most promising therapeutic modalities for arterial and venous thrombosis, but careful dosing and monitoring of thrombolytic therapy are required. In addition, careful attention and observation of the patient and often the limb undergoing treatment is required.

Fibrinolytic System

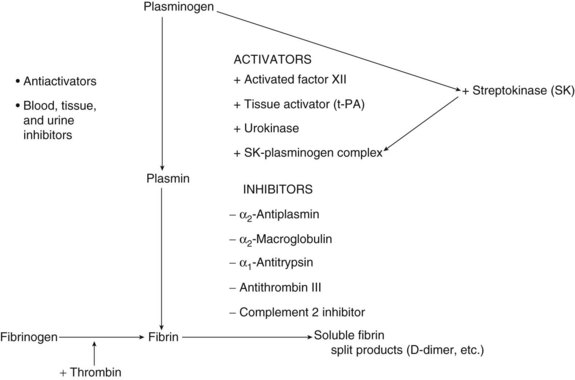

The complex and intricate relationships among all components of the fibrinolytic system are only partially understood. Much progress has been made, however, mostly owing to recognition of the importance of the fibrinolytic system as a homeostatic system. This same process has been harnessed for a therapeutic effect in cases of clinical thrombosis. The concept of dynamic equilibrium was proposed by Astrup in 1958.6 In a delicate balance, fibrinolysis breaks down fibrin, which is continuously being deposited throughout the cardiovascular system. This is the result of limited activation of the coagulation system. This baseline fibrinolytic activity is probably under local and central control mechanisms. The feedback loop that prevents systemic fibrinolysis involves both inhibitors at the activator level and specific inhibitors of the proteolytic enzyme plasmin.

The final common pathway in the fibrinolytic system is the conversion of the proenzyme plasminogen to the active enzyme plasmin. Plasminogen is a glycoprotein produced by the liver. Full-sized plasminogen can be divided into a heavy N-terminal region that consists of five homologous but distinct triple-disulfide–bonded domains (kringles) fused to a lighter catalytic C-terminal domain. At least four forms occur in plasma, based on variations in the N-terminal and the degree of glycosylation. The two main forms are Glu-plasminogen and Lys-plasminogen.7 Glu-plasminogen contains glutamic acid and exists in high concentrations in plasma. Lys-plasminogen, containing mostly lysin in the N-terminal, results from limited proteolysis of the Glu form; it has a shorter half-life and is found in higher concentrations in thrombus, most likely secondary to its higher affinity for fibrin.8 A schematic view of the fibrinolytic system is presented in Figure 33-1.

The kringle portion of plasminogen is a nonprotease, or heavy chain, consisting of five homologous domains. These domains exhibit a high degree of sequence homology with one another and with domains found in prothrombin, tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA), urinary plasminogen activator, and factor XII. Kringle-4 shares homology with apolipoprotein A. The function of these kringles is thought to be of paramount importance in the binding of plasminogen and plasmin to fibrin, α2-antiplasmin, and other macromolecules.9,10 In addition, the kringle portion of plasminogen has been implicated in mediating neutrophil adherence to endothelial cells.11 On binding, conformational changes occur that transform a closed structure into an open structure. ε-Aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid induce this change from the closed structure to the open structure. Because of this change, plasminogen is far more readily cleaved to the active enzyme plasmin by plasminogen activators. The open conformation also binds more readily to exposed lysine residues on fibrin’s surface. Concentrations of lysine analogs, such as tranexamic acid and aminocaproic acid, that actually promote the more active, open conformation of Glu-plasminogen also prevent its binding to fibrin and therefore exhibit an antifibrinolytic effect.12

The primary substrates for the proteolytic activity of plasmin in circulation are fibrinogen and fibrin. Circulating fibrinogen is composed of three polypeptide chains known as the α, β, and γ chains. These chains are bonded together by disulfide bonds, which are also linked to a second identical chain, thus making fibrinogen a dimer of trimers. Thrombin, the common pathway of the coagulation cascade, removes several amino acid peptides from the end terminal of the α chain, the β chain (fibrinopeptide B), to form fibrin. As new sites are exposed, staggered polymerization is initiated.7 Through catalysis by factor XIIIa, the domains are brought together and chemically cross-linked. Plasmin catalyzes the hydrolysis of these bonds, producing peptides that can be assayed in circulation. Specifically, those produced after the cleavage of fibrinogen consist of truncated polypeptides collectively known as X fragments. X fragments can be incorporated into both newly forming and existing thrombi, causing them to be more fragile. This has been proposed as a possible explanation of why fibrin-specific fibrinolytic agents such as t-PA do not result in fewer bleeding complications compared with nonspecific agents. Because t-PA is such a potent fibrinolytic activator, the accumulation of these X fragments could make existing thrombi more susceptible to its fibrinolytic action. Several fragments are specifically produced by the action of plasmin on fibrin, as opposed to fibrinogen. Unique fragments such as d-dimers can be assayed, documenting fibrinolysis as opposed to fibrinogenolysis.13

Plasmin is a relatively nonspecific protease and thus can hydrolyze many proteins found in plasma and extracellular spaces. Known targets of plasmin are factors V and VIII and von Willebrand factor.1 Prothrombotic activity can be shown with the initial administration of fibrinolytic agents (specifically t-PA and streptokinase, which may relate to the release of fibrinopeptide A). Plasminogen can also cause the release of kinin from high-molecular-weight kininogen. In addition, it can directly and indirectly activate prekallikrein, again inducing kinin formation.14,15 Plasmin can also attack protein components of the basement membrane, as well as other active proteases within the matrix, including fibronectin, collagen, and laminin.7

Activation of factor XII by various stimuli results in initiation of the coagulation cascade, conversion of prekallikrein to kallikrein and kinin (inflammatory response), and formation of plasmin from plasminogen. This intrinsic mechanism of activation is complemented by a second intrinsic pathway that is not dependent on factor XII. The main pathway for plasminogen activation is known as the extrinsic system. Two activators are recognized in humans: urokinase-type plasminogen activator (u-PA) and t-PA. Their physiologic activity is controlled by inhibitors, mostly plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI) type 1 (PAI-1) and type PAI-3. These inhibitors control the activity of the activators in plasma and possibly at the cellular level. PAI-1 is synthesized in the liver and vascular endothelial cells and is normally present in trace amounts in plasma. PAI-1 elevation leading to prothrombotic states is becoming increasingly recognized. When pharmacologic doses of these agents are administered, the inhibitor activity is suppressed. It is estimated that one third to half of the initial pharmacologic dose of urokinase, for example, becomes inactivated shortly after administration.11 Once plasminogen has been converted to plasmin, inhibitors of plasmin come into play. The main physiologic inhibitor of plasmin is α2-antiplasmin. This protease inhibitor is a single-chain glycoprotein that inhibits plasminogen in two steps: a fast reversible binding step, followed by the formation of a covalent complex involving the active site of plasmin.7 The half-life of this complex is approximately 12 hours.16 Other inhibitors of plasmin include α2-macroglobulin, protease nexin, and aprotinin. Protease nexin is a broad-spectrum inhibitor of serine proteinases and inhibits, among others, trypsin, thrombin, urokinase, plasmin, and one- or two-chain t-PA. Once bound, these proteases are internalized via nexin receptors on the cell surface and rapidly degraded.17 Aprotinin, also known as basic pancreatic trypsin inhibitor, has been isolated and purified and is sold under the name Trasylol (Bayer, West Haven, Conn.). It is also a potent inhibitor of trypsin and kallikrein, in addition to plasmin. The use of bovine aprotinin to reduce postoperative bleeding after major surgery has been reported.18,19 In animal models, it has been shown to serve as an antidote to bleeding induced by the administration of recombinant t-PA (rt-PA).20 Because aprotinin inhibits plasmin and not the activator, it should work with other plasminogen activators.

A link between lipoprotein metabolism and fibrinolytic function has been suggested by the demonstration of significant homology between the amino acid sequence of apolipoprotein A and the structure of plasminogen. Thus, a prothrombotic function by virtue of interference with the numerous physiologic functions of plasminogen has been suggested in patients with increased levels of apolipoprotein A. Apolipoprotein A has also been found to competitively inhibit the binding of plasminogen to fibrinogen and to the plasminogen receptor on endothelial cells.26

Plasma levels of both t-PA and PAI-1 exhibit circadian variations. For example, t-PA activity is lowest in the early morning and highest in the afternoon. Plasma PAI activity peaks in the early morning and passes through a trough in the afternoon. Thus, overall there is decreased fibrinolytic activity in the morning.27–30 Differences in patterns have been observed between men and women, suggesting a hormonal influence.31 Furthermore, PAI activity has been noted to vary secondary to diet, with caffeine-containing beverages possibly enhancing fibrinolytic activity. Conversely, cigarette smoking induces an acute increase in t-PA; this increase in t-PA may deplete normal stores and thus paradoxically decrease fibrinolytic capacity.

Thrombolytic Agents

The use of thrombolytic agents has clearly resulted in a significant improvement in the outcome of patients with acute cardiac ischemia, myocardial infarction, and cerebral infarction. It has also resulted in a modification in the treatment algorithm for patients with peripheral arterial occlusion. Thrombolytic therapy is an important treatment option for patients with vascular occlusive disease. Table 33-1 summarizes the characteristics of some of the common thrombolytic agents. Several schemes may be used to classify thrombolytic agents. The agents can be grouped by their mechanism of action—those that directly convert plasminogen to plasmin versus those that are inactive zymogens and require transformation to an active form before they can cleave plasminogen. Agents can be classified by their mode of production. In addition, thrombolytic agents can be classified by their pharmacologic actions—those that are fibrin specific (i.e., bind to fibrin but not to fibrinogen) versus those that are nonspecific, and those that have a great degree of fibrin affinity (i.e., bind avidly to fibrin) versus those that do not. Another useful classification of thrombolytic agents is groups based on their origin: the streptokinase compounds, the urokinase compounds, the tissue plasminogen activators, and an additional group consisting of novel agents. In the following sections, we have divided thrombolytic drugs chronologically.

First-Generation Thrombolytic Drugs

Streptokinase

Streptokinase is a single-chain nonenzymatic protein produced by β-hemolytic streptococci. Its discovery by Tillett and Garner32 in 1933 revived an interest in fibrinolysis that has spanned the past 7 decades. Early clinical experience was complicated by a multitude of pyogenic and allergic reactions. This prompted manufacturers to refine the drug, achieving the currently purified product and a marked reduction in febrile and allergic reactions.

From the foregoing discussion, it is evident that precise control of thrombolysis is not possible because the dose-response relationship of streptokinase varies from patient to patient. Initially, clinical use was guided by titers of antistreptococcal antibodies and measurement of the various components or products of the system. This proved impractical, and current practice relies on standardized dosages that achieve the desired effect in the great majority of cases. A potential drawback of this approach is that excess amounts of drug could use most of the circulating plasminogen to form activator complex; this might leave inadequate amounts of zymogen to convert to plasmin. This problem of exceeding plasminogen availability may be important during regional, rather than systemic, administration. Some investigators have combined streptokinase with plasmin administration, resulting in improvements in measured parameters such as plasminogen level, fibrinogen level, and potential fibrinolytic capacity.33 Similar results are obtained by intermittent rather than continuous infusion of the drug. Unfortunately, the results of these noncontrolled trials have raised doubts about the effectiveness of such regimens. Streptokinase has largely fallen out of favor, partly because of the immunogenicity of even the refined form, which can result in fever, allergic reactions, and acquired drug resistance. A complex of streptokinase and anisoylated plasminogen streptokinase activator complex (APSAC), or anistreplase, was developed in an attempt to solve some of the problems inherent to streptokinase. It is an acylated complex of SK with human lys-plasminogen. The potency of APSAC has been found to be tenfold that of SK, but it has a longer half-life. Although conceptually sound, clinical trials were unable to demonstrate any increase in efficacy or any decrease in antigenicity with the administration of APSAC.

Urokinase

Urokinase is a serine protease with direct activator activity; it is normally present in urine as a product of renal tubular cells. It was originally isolated by MacFarlane and Pilling in 1947.34 Urokinase is present in varying molecular weights, with variable activity. Original purification was done from urine, yielding small amounts of the enzyme at a considerable cost. Newer production methods use human fetal kidney cell culture.

Urokinase is nonantigenic, and its mechanism of action is much more direct compared with that of streptokinase. Urokinase cleaves plasminogen (its only known protein substrate), by first-order reaction kinetics, to plasmin. It is pH and temperature stable. The lack of circulating neutralizing antibodies and its direct mechanism of action allow for a predictable dose-response relationship. Although allergic reactions are rare, over the last few years a febrile response to drug administration has become more common. It has been suggested that this may be related to interleukins that are still present in recently manufactured drug batches. In the past, when the use of urokinase was less common, aging of the drug actually allowed the interleukins to become inactive. These febrile reactions respond readily to antipyretics. Interestingly, urokinase does not contain any lysine binding sites and therefore does not have any fibrin binding properties.35 High-affinity receptors for urokinase, however, have been demonstrated in several cell types and have been postulated as a mechanism by which cells can invade the intracellular matrix and play a role in other physiologic and pathologic processes.36–38

Urokinase is a serine protease and hydrolyzes synthetic esters containing arginine and lysine. Unlike streptokinase, urokinase directly activates plasminogen by cleaving the Arg560-Val561 activation bond. The activation of plasminogen by urokinase occurs by proteolysis. When administered intravenously, urokinase is rapidly removed from the circulation, mainly via hepatic clearance. It has been estimated that the half-life of urokinase in humans is on the order of 14 minutes. Urokinase also reacts with other proteins, including fibrinogen. Urokinase is much more effective in cleaving the susceptible site in plasminogen when it is in the Lys form than in the Glu form. However, the activation reaction of the latter by urokinase may be enhanced by the presence of fibrin.39 Administration of exogenous plasminogen may also accelerate thrombolysis by urokinase.

Controversy exists regarding the actual thrombolytic effect of urokinase when administered in vivo. Experimental studies have suggested exogenous fibrinolysis as the main pathway, with limited activation of plasminogen within the thrombus (endogenous fibrinolysis).40 In clinical practice, the results of urokinase therapy have paralleled those achieved with streptokinase, with a decreased incidence of bleeding complications suggested by several investigators.42–44 Whereas major bleeding complications are seen in 15% to 20% of patients treated with streptokinase, such complications have been reported in only 5% to 10% of patients treated with urokinase. Thus, the benefits observed in laboratory results and the reduced incidence of significant plasminemia with urokinase seem to translate into a decreased incidence of bleeding complications in clinical practice. Although the cost of urokinase remains high compared with that of streptokinase, when complications are considered, the cost of therapy for streptokinase and urokinase is comparable.45

Residual thromboplastic activity was detected in the early urokinase preparations,46 and this may account for the initial hypercoagulable state reported by Kakkar and Scully.47 At present, this does not appear to be a clinically significant problem.

Despite the drug’s record of safety and efficacy accrued over the years, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration halted the release and use of urokinase, manufactured by Abbott Laboratories, on the grounds of deviations from the FDA’s current good manufacturing practices guidelines, developed to prevent the manufacture of unsafe products. The FDA inspection of Abbott’s manufacturing facility in North Chicago in 1998 raised concerns about the neonatal kidney cells that were being used as a source of urokinase.48,49 The cells originated from Cali, Colombia, and were obtained through a separate company. The source population was thought to be at high risk for various diseases, including tropical ones, and although there were no documented cases of infectious transmission resulting from urokinase administration. The FDA stated that any connection between the drug and such cases might have gone unrecognized.

In October 2002, the FDA approved the reintroduction of urokinase to the market after Abbott made significant changes in its quality-control and manufacturing practices. Urokinase was approved for use in the treatment of pulmonary embolism. Although it has not been approved for use in the peripheral arterial and venous systems, many practitioners have experience with off-label use in the periphery. During the time that urokinase was unavailable, increased experience and familiarity were gained with other agents, such as rt-PA and reteplase.50

Second-Generation Thrombolytic Drugs

Tissue Plasminogen Activator

Tissue plasminogen activator is a naturally occurring enzyme present in all human tissues. Its concentration is variable, with high levels detected in the uterus and moderate amounts in the heart, skeletal muscles, kidneys, ovaries, lungs, thyroid, pituitary, and lymph nodes. Scant amounts of t-PA are found in the liver, spleen, brain, and testes.51 It is thought to originate from vascular endothelium, and, with the exception of the liver and spleen, tissue concentration correlates with vascularity.

Isolation and purification of t-PA were initially hampered by inadequate sources and procedures. In 1979, Rijken and associates52 were successful in obtaining 1 mg of t-PA from 5 kg of human uterine tissue. Recognizing the potential of this drug, investigators have concentrated on other sources.

At present, there are two main sources of t-PA. The Bowes melanoma cell line is uniquely efficient in producing large quantities of t-PA,53 which was subsequently proved to be identical to uterine t-PA.54 Another source has emerged from the use of recombinant DNA technology, and efforts in the cloning and expression of the t-PA gene from the melanoma cell line have been successful. Since 1987, when rt-PA was approved for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction, it has been used for peripheral thrombolysis as an alternative to urokinase.

In general, plasminogen activators do not cause clot dissolution directly; they must first find and activate molecules of plasminogen in the vasculature at the site of the clot. t-PA is a direct plasminogen activator. Its main advantage is its high affinity for thrombus-bound fibrin. The agent exhibits significant fibrin specificity. t-PA is a poor enzyme in the absence of fibrin. However, the presence of fibrin strikingly enhances the activation rate of plasminogen by t-PA. Two types of t-PA are recognized, with a commercial preparation being a mixture of both types. A single-chain form is cleaved by plasminogen to yield two-chain t-PA. The one- and two-chain forms of t-PA are comparable in activity, with the one-chain form being quickly converted to the two-chain type as lysis proceeds. Most of the circulating t-PA is in the single-chain form. Its selective action promises to produce fewer systemic effects when compared with streptokinase or urokinase.55 The half-life of t-PA has been estimated to be between 4 and 7 minutes in vivo.56 With its presumed nonantigenicity and high affinity for fibrin, t-PA theoretically should produce improved clinical results.

When fibrin-selective agents are used for regional infusion, most of the thrombolytic effect is secondary to fibrin-bound plasminogen. However, the importance of a fresh supply of plasminogen to maintain the fibrin-bound plasminogen pool has been emphasized. Experimental studies have suggested that clot lysis induced by the activation of plasminogen is dependent on clot-associated plasminogen, which in turn depends on the concentration of plasminogen in plasma. Depletion of both contributes to less frequent and less rapid recanalization, which is more noticeable with non–fibrin-selective agents than with fibrin-selective ones, likely the result of the depletion of plasminogen induced by the nonselective agents.57

Trials comparing rt-PA with streptokinase in patients with acute coronary thrombosis have failed to establish that this more specific drug is a better thrombolytic agent. Systemic bleeding complications have been similar, despite a milder homeostatic defect by laboratory evaluation in the rt-PA groups.58 Questions still exist regarding proper dosage to achieve effective local lysis with minimal systemic effects.

Tissue plasminogen activator may also bind and be activated on platelet surfaces.59 Owing to this binding to platelet receptors, platelets can direct t-PA action on their surface, leading to rapid cleavage of glycoprotein Ib and the loss of platelet binding to von Willebrand factor. This may explain why concentrations of t-PA achieved early in therapy may inhibit platelet aggregation.

In animal models of thrombolysis, it has been suggested that multiple bolus administrations of t-PA have greater lytic efficacy than equal doses given as a single bolus or a continuous infusion.60 This may have significant implications for clinical therapy, in which protocols requiring continuous infusion of the agent have shown a greater incidence of bleeding complications than protocols in which the drug is administered in bolus form. This might be explained by the accumulation of partially degraded fibrin (X fragments), which might increase the affinity of t-PA for plasminogen by about 17-fold.7

In a study in which 17 patients were infused with rt-PA at a rate of 0.1 mg/kg per hour, all patients demonstrated thrombolysis, with 16 showing clinical improvement.61 More important, there were no systemic complications, with a mean fibrinogen drop of 42% of baseline. The infusion time was 1 to 6 hours, compared with the usual 48 to 72 hours necessary for streptokinase infusion. One patient died from an intracranial hemorrhage during postinfusion heparin therapy. Experience in randomized trials has suggested that a lower dose is just as effective, with a decreased risk of bleeding. The recommended lower dose is 0.05 mg/kg per hour.62

Pro-Urokinase

Saruplase, also known as recombinant single-chain urokinase-type plasminogen activator, or pro-urokinase, is a prodrug produced from a naturally occurring physiologic protease.62 Pro-urokinase is a single-chain polypeptide of 411 amino acids that is converted by plasmin into an active, low-molecular-weight form of urokinase with 276 amino acids.63 Pro-urokinase functions as a potent plasminogen activator of fibrin-bound plasminogen without requiring extensive systemic conversion to two-chain urokinase. Thus, the entire thrombolytic process is confined to the fibrin clot itself. Administration of pro-urokinase causes decreases in α2-antiplasmin and fibrinogen and an increase in fibrinogen degradation products. Pro-urokinase is highly effective in the conversion of Lys-plasminogen to plasmin. In contrast, it has little or no activity in the conversion of Glu-plasminogen to plasmin. Because Lys-plasminogen is present in high concentrations in thrombus, this gives pro-urokinase fibrin-specific properties. In addition, plasminogen that is absorbed in thrombus changes its configuration to a pseudo–Lys-plasminogen, which is also attacked by pro-urokinase, converting it to Lys-plasmin. Circulating pro-urokinase is very stable in plasma because of its resistance to plasma inhibitors and ionized calcium.64 The fibrin specificities of t-PA and pro-urokinase appear to rely on different mechanisms. Whereas t-PA is fibrin clot binding, the fibrin-selective properties of pro-urokinase are thought to be secondary to its preference for activation of Lys-plasminogen or Lys-like–plasminogen substrate found in thrombus. This effect prolongs half-life, which has been estimated to be several days. Such a prolonged half-life has theoretical advantages in clinical situations in which prolonged activity is desired. However, in peripheral arterial occlusions, if the regional infusion fails to produce the desired result and the patient must go to the operating room shortly after discontinuation of the infusion, this prolonged effect may be undesirable.

A recombinant form of pro-urokinase is Prolyse (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL). This urokinase compound has the advantage of not originating in a human cell source. Many of the clinical trials using this drug have been studies of patients with myocardial infarction, where the notable finding was an increased incidence of intracranial hemorrhage (0.9%).65 The most recent trial was the Prolyse in Acute Cerebral Thromboembolism II (PROACT II) study, which evaluated intraarterial pro-urokinase for acute ischemic stroke.66 Early intracranial hemorrhage with neurologic deterioration within 24 hours occurred in 10% of pro-urokinase patients and 2% of control patients. Although pro-urokinase is effective at thrombolysis, the increased bleeding risk has limited its widespread use. A phase II trial evaluating pro-urokinase versus urokinase for thrombolysis of acute peripheral arterial occlusion showed that pro-urokinase had a greater efficacy, but an increased risk of bleeding complications at a dose of 8 mg/hour; with a dose of 2 mg/hour, there was a slightly lower rate of thrombolysis, combined with a lower incidence of bleeding complications and fibrinogenolysis.67

Third-Generation Thrombolytic Drugs

The last few years have seen the development of a new generation of thrombolytic drugs, including mutant molecules of single-chain u-PA and t-PA; chimeric plasminogen activators; conjugates of plasminogen activators with monoclonal antibodies against fibrin, platelets, or thrombomodulin; and plasminogen activators of animal and bacterial origin.50

Reteplase

Reteplase is a single-chain deletion mutant of alteplase, consisting of just the kringle-2 and protease domains.68 Reteplase has a fivefold decrease in fibrin binding and a half-life of 14 to 18 minutes because of the aforementioned structural differences. Reteplase has less binding to endothelium and monocytes compared with t-PA, and this reduced binding results in increased circulating levels in the bloodstream.69 Reteplase catalyzes the cleavage of endogenous plasminogen to generate plasmin. The activation of plasminogen is stimulated in the presence of fibrin and is mediated by the kringle-2 domain.10,70 Plasmin then degrades the fibrin matrix of the thrombus, thus exerting its fibrinolytic action.

Reteplase has increasingly been used in the treatment of peripheral vascular occlusion, given the unavailability of urokinase for a few years. Nevertheless, published studies regarding its use in controlled trials are relatively few in number. There are two pilot studies that evaluated the dosing regimen of reteplase in the treatment of myocardial infarction.71,72 These studies demonstrated that reteplase produced significantly higher TIMI-3 (thromboembolism in myocardial infarction) flow rates at 60 and 90 minutes than did front-loaded alteplase. However, in two subsequent trials—the International Joint Efficacy Comparison of Thrombolytics (INJECT)73 and Global Use of Strategies to Open Occulated Coronary Arteries (GUSTO III)74 trials—despite the higher TIMI-3 flow rates, this did not translate into a lower mortality in the reteplase-treated patients (7.5% for reteplase vs. 7.2% for alteplase).15 Reteplase has lower fibrin affinity and thus appears to penetrate thrombus effectively and activate fibrin-bound plasminogen within the clot, resulting in faster clot lysis. Thrombolytics may also cause platelet activation, and this may have been responsible for some of the previously noted lack of efficacy. The addition of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors appears to increase the efficacy of thrombolytic agents, as well as speed the lysis.

Tenecteplase

Tenecteplase (TNK-t-PA) is a t-PA mutant in which a threonine molecule (100Thr) is replaced by Asn, and the sequence Lys-His-Arg-Arg is changed to Ala-Ala-Ala-Ala. This change confers high fibrin selectivity and prolongs the half-life to 15 to 19 minutes. TNK-t-PA is highly effective in arterial, platelet-rich thrombi and is more resistant to plasminogen activator inhibitor. Although most of the published data regarding TNK-t-PA have been related to acute coronary syndromes, there is increasing experience in peripheral arterial thrombolysis. One group published its experience with continuous tenecteplase infusion in conjunction with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition with tirofiban for peripheral arterial thrombolysis.75 The dose of TNK-t-PA infusion was 0.25 to 0.50 mg/hr, with a mean infusion time of 7.5 hours. Of 48 patients with iliofemoral arterial thrombosis, complete lysis was achieved in 35 patients (73%). There were no deaths, no intracranial bleeding, and no embolic events. It appears, at least from this study, that lysis time is shorter; however, the longer half-life has implications for surgical intervention, as addressed earlier.

Staphylokinase

Staphylokinase is a plasminogen activator produced by certain strains of Staphylococcus aureus and was first described as having fibrinolytic properties in 1948.76 The gene has been cloned from genomic DNA of a lysogenic strain of S. aureus. When exposed to a fibrin clot in human plasma, staphylokinase reacts with plasmin at the clot-plasma interface; this staphylokinase-plasmin complex activates thrombus-bound plasminogen and exerts its fibrinolytic activity. Any plasmin that is liberated from the clot is rapidly inactivated by α2-antiplasmin. In this manner, plasminogen activation by staphylokinase is confined to the thrombus, and the collateral effects of fibrinogen depletion and serum plasminogen activation are minimized. Patients treated with staphylokinase do, however, develop neutralizing antibodies, the titers of which can remain elevated for several months.77

Immunofibrinolysis

In an attempt to develop fibrin-specific agents, monoclonal antifibrin antibodies have been bonded to urokinase or streptokinase, rendering these agents fibrin selective. These monoclonal antibodies do not appear to cross-react with fibrinogen and thus show a marked increase in in vitro fibrinolysis compared with unmodified activator.78 The clinical applicability of these agents remains to be determined; they may significantly alter the current approach to the management of thrombotic disease. Nevertheless, repeated therapy would require different monoclonal antibodies to prevent adverse immunologic reactions.

Venous Thrombolysis Including Systemic Thrombolytic Therapy

Patient Selection

Contraindications to systemic therapy are listed in Box 33-1. Absolute contraindications are active internal bleeding and recent (within 2 months) cerebrovascular accident or other intracranial condition. Relative major contraindications include recent (within 10 days) major surgery, trauma, obstetric delivery, organ biopsy, or puncture of a noncompressible vessel; recent gastrointestinal bleed; and severe hypertension. Relative minor contraindications carry a higher risk of complications, but the benefits of therapy may still outweigh the hazards. Peripheral embolization from a central source is a potential hazard of systemic lytic therapy. Therefore valvular heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and previous history of emboli are relative contraindications to systemic lytic therapy. The presence of a mural thrombus is a relative contraindication to fibrinolytic therapy because of the potential for peripheral embolization due to fragmentation, which could have devastating consequences. In patients with a thrombus in the left side of the heart demonstrable by echocardiography, alternative forms of treatment should be considered. It must be recognized, however, that successful lysis of ventricular thrombi with urokinase has been reported.79 Severe liver disease affects drug metabolism, making the response unpredictable. During pregnancy, a systemic lytic state may precipitate abruptio placentae or lead to hypofibrinogenemia in the fetus, with an increased risk of bleeding. Streptokinase is specifically contraindicated in patients with known allergy, previous therapy within 6 months, or recent streptococcal infection.

One of the most devastating complications of fibrinolytic therapy is intracranial hemorrhage. The incidence of this complication is approximately 1% of treated patients in trials for acute myocardial infarction. The median time between the start of thrombolytic therapy and the onset of clinical signs of intracranial hemorrhage ranges from 3 to 36 hours, with a mean of 16 hours. Mortality is high for this complication, with an estimated mortality of 66%. Factors predictive of intracranial hemorrhage by multivariate logistic regression analysis include oral anticoagulation before admission, body weight less than 70 kg, and age older than 65 years. An increased incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage has been observed in patients receiving higher doses of t-PA. In the Thrombosis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) trial,80 1.3% of patients receiving 150 mg of t-PA suffered an intracerebral hemorrhage, as opposed to 0.4% of patients receiving 100 mg of the drug. Interestingly, in the TIMI-II trial, patients who received immediate β blockade as part of their regimen had no incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage when given 100 mg of t-PA, compared with 0.5% in the group that did not receive β blockade. This was not true, however, for patients treated with 150 mg of t-PA. The mechanism by which β-blockers may protect against intracerebral bleeding has not been established.81

In the Surgery versus Thrombolysis for Ischemia of the Lower Extremity (STILE) trial, patients were randomized to thrombolytic therapy with t-PA or urokinase versus surgery for the treatment of lower limb ischemia.82 When evaluated with an intent-to-treat analysis, the incidence of life-threatening hemorrhage was 5.3% to 5.7%. When analyzed on a per-protocol basis, the incidence of this complication was 7.8% in the thrombolysis group. The incidence was similar in patients treated with t-PA and urokinase; these patients also received aspirin and heparin, which may have added to the risk. However, patients with bleeding complications did not receive more heparin or a higher dose of lytic agent; they appeared to respond differently to the therapy. At the end of the infusion, patients with bleeding complications had a significantly lower fibrinogen level than did patients without hemorrhagic complications (188 vs. 310 mg/dL). Measurement of fibrinogen levels, along with the international normalized ratio and partial thromboplastin time (PTT), may be helpful in guiding dose and duration of therapy.

Indications

Pulmonary Embolism

In 1968, a cooperative, controlled, randomized study to evaluate the use of urokinase in pulmonary embolism was initiated.83 By 1970, 160 patients were entered and assigned to one of two therapeutic arms. Pulmonary angiography was performed on all patients before and after therapy, with lung scans repeated at 3, 6, and 12 months. The minimal eligibility was occlusion of at least one segmental pulmonary artery on angiography. Excluded from the trial were patients who had recent operations and those with contraindications to heparin or thrombolytic therapy. Seventy-eight patients received anticoagulants alone (heparin 75 units/lb loading dose, 10 units/lb per hour for 12 hours), and 82 received urokinase (2000 units/lb per hour for 12 hours). After the 12-hour infusion, all patients received heparin for a minimum of 5 days to maintain a prolonged bleeding time.

In 1974, the second phase of this cooperative study was reported.84 This study followed the same guidelines as in phase I, comparing 12 hours of urokinase therapy with 24 hours of urokinase therapy and 24 hours of streptokinase therapy. A group treated with heparin alone was not included because the protocol was almost identical to that in the phase I trial, which showed urokinase to be superior to heparin in clot resolution. Fifty-seven patients were given urokinase (2000 units/lb loading dose, 2000 units/lb per hour for 24 hours), and 61 patients received the same regimen for 12 hours. Fifty-eight patients received streptokinase (250,000 units loading dose, 100,000 units/hr for 24 hours).

One of the major problems with the use of thrombolytic therapy for pulmonary embolism is that these patients usually have major contraindications to thrombolytic therapy. For example, this is the case with pulmonary embolism in a postoperative patient. In 1992, an experience with 13 patients treated for angiographically proven pulmonary embolism within 14 days of surgery was reported.85 The protocol used urokinase (2200 units/kg body weight) injected directly into the clot through a catheter positioned in the pulmonary artery. A continuous infusion at the same dosage was then maintained for up to 24 hours, with the simultaneous administration of heparin at 500 units/hr. The fibrinogen level was maintained at less than 0.2 g/dL. No deaths or bleeding complications were seen, with complete lysis achieved in all patients. This selective therapy for pulmonary embolism may be appropriate for patients in the early postoperative period who suffer a major life-threatening pulmonary embolus.

The long-term results of patients randomized to the Urokinase Pulmonary Embolism Trial (UPET) suggest the clinical importance of resolution of the obstructive process in the pulmonary circulation. Several patients from this study were reexamined 7 years after the original pulmonary embolus. Those assigned initially to thrombolysis had significantly higher pulmonary capillary blood volumes and preservation of the normal pulmonary vasculature response to exercise at 7 years. In contrast, patients who had been treated with anticoagulants alone demonstrated a lower pulmonary capillary blood volume at 1 year and a markedly abnormal increase in pulmonary artery pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance when undergoing exercise testing during right heart catheterization.86 These data suggest that initial management with thrombolysis can offer improved quality of life years after the event.

More recently, rt-PA has been evaluated in the treatment of acute massive pulmonary embolism. In a multicenter trial, the intravenous administration of rt-PA was compared with intrapulmonary administration in 34 patients with massive pulmonary emboli.87 All patients were systemically anticoagulated with heparin. The patients received 50 mg of intravenous or intrapulmonary rt-PA over 2 hours, with 22 patients receiving another 50 mg over the subsequent 5 hours. No difference was noted between the intrapulmonary group and the intravenous group, and 7-hour administration was superior to a single infusion of 50 mg over 2 hours. In all groups, up to 38% resolution of the angiographically determined embolism occurred. A decline in the pulmonary arterial pressure was documented in all groups. Fibrinogen levels dropped significantly, and bleeding complications were limited to puncture or operative sites; only four patients required blood transfusions.

In a separate trial, 36 patients with angiographically documented pulmonary emboli received 50 mg of rt-PA over 2 hours, followed by repeated arteriography and, if necessary, an additional 40 mg of rt-PA over 4 hours.88 Thirty-four of the 36 patients had angiographic evidence of clot lysis, with marked improvement in 24 of the 36. Two bleeding complications occurred, one related to a pelvic tumor and the other 8 days after coronary artery bypass surgery. Again, significant improvement in the clinical condition of these patients was documented.

A randomized, controlled trial of rt-PA versus urokinase in the treatment of acute pulmonary embolism was reported in 1988.89 Forty-five patients were randomized to 100 mg of rt-PA over 2 hours versus urokinase at systemic doses. At 2 hours, 82% of the rt-PA patients had complete lysis, as opposed to 48% of patients receiving urokinase. Eight of 23 urokinase patients required premature termination of the infusion because of bleeding complications. There was no difference in plasma fibrinogen level or improvement in lung scans between the two groups.

In 1980, the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference concluded that thrombolytic therapy results in greater improvement and normalization of the hemodynamic responses to pulmonary emboli than that observed with heparin alone.90 Lytic therapy may prevent permanent damage to the pulmonary vascular bed by lysing emboli and restoring the pulmonary circulation to normal. The conference report also stated that although the incidence of bleeding complications was high, contemporary clinical experience suggested an incidence of approximately 5%, which was certainly within the acceptable range.

The thrombolytic agents currently approved by the FDA for use in the treatment of patients with pulmonary embolism are t-PA, given in a 100-mg dose over 2 hours, and, since 2002, the newly reintroduced urokinase. As stated earlier, there is no evidence of improved survival or outcomes in patients with pulmonary embolism who are hemodynamically stable. Tebbe and colleagues91 evaluated the efficacy of reteplase, given as two 10-unit boluses 30 minutes apart, compared with t-PA in the 100-mg dose. There was no difference in clinical outcomes, complications, or mortality. The rates of stroke and intracranial hemorrhage were similar. However, reteplase reduced pulmonary vascular resistance more quickly than t-PA did. However, it should be emphasized that there is no level I evidence that thrombolysis for the improvement of pulmonary embolism offers any survival advantage, except in cases of massive embolism with hemodynamic compromise.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree