Chapter 50 Endovascular Repair of Chronic Venous Obstruction

Percutaneous endovenous stenting has emerged as a powerful new technique to treat chronic venous obstructions. Stenosis and chronic total occlusions (CTOs) are amenable to endovascular correction.1–4 The technique is minimally invasive, safe, and effective and does not preclude open correction in case of failure. The technique can be applied in the geriatric subset and others with comorbidities that would normally preclude open procedures. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) diagnostics have revealed that obstruction is present in a broader spectrum of chronic venous disease (CVD) than previously imagined.5 Furthermore, stent correction of obstruction alone in combined obstruction–reflux appears to yield good symptom relief even when the reflux component remains uncorrected6; this suggests that the pathophysiologic importance of obstruction has been underestimated.7 These observations suggest a broad, dominant role for stent usage in highly symptomatic CVD patients which signifies a major therapeutic paradigm shift in the management of advanced CVD.

Pathophysiology

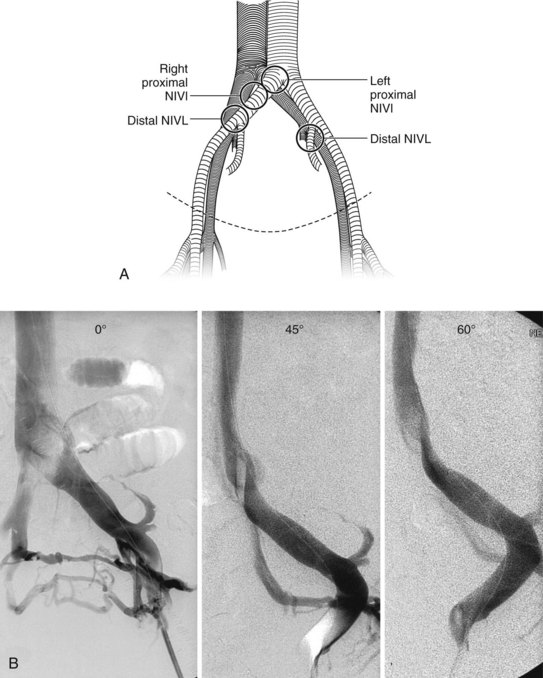

Postthrombotic etiology for chronic venous obstruction is well established. With the use of IVUS, it has become clear that nonthrombotic iliac vein lesions (NIVLs) are a common feature among “primary” CVD patients with advanced symptoms as well.5 The lesions occur at arterial crossover points over the vein (Figure 50-1). Intraluminal webs and strictures are often present and are thought to result from pulsatile trauma of intimately associated artery.8 Other less common causes of chronic venous obstruction include tumors, retroperitoneal fibrosis and radiation injury. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters are also emerging as a significant cause of iatrogenic caval-iliac obstruction; some models appear to be more prone to this development than others.9

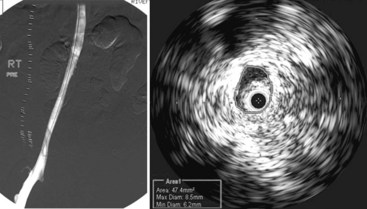

Postthrombotic disease often involves multiple venous segments, but symptom production appears to be mainly related to the iliac vein segment because of poor collateral potential in this venous segment.10 Natural collateral pathways based on embryology appear to develop rapidly in obstructions of other venous segments, particularly in femoral vein obstructions and to a lesser extent in caval obstructions. These collateral pathways may exist already in putative form, becoming functional when straight-line flow faces higher resistance than in the quiescent collaterals.11 The process is just the reverse of that seen in venous stenting when collaterals disappear instantaneously with clearance of obstruction. The profunda femoris vein is an embryologic collateral and often becomes visible on venography within a few hours after onset of femoral vein thrombosis. CTO lesions of the IVC are sometimes an incidental finding in asymptomatic patients.10 In contrast, pelvic vein collaterals that appear impressive on venography are often functionally inadequate, and the patient continues to be symptomatic.12 Some postthrombotic iliac vein lesions develop a tough perivenous sheath that restricts the vein and retards collateral development. Such diffuse iliac vein stenosis, first noted by Rokitanski in autopsy studies, appears as a patent but smaller caliber iliac vein on venography. The reduction in lumen size is clearly evident on IVUS examination, but is easily missed on venography (Figure 50-2). Focal iliac vein lesions may be impervious to routine venography as well.13 For these reasons, a symptomatic iliac vein lesion may remain occult, whereas the more obvious femoral vein occlusions are readily apparent. The latter are seldom the main source of symptoms, however, and a diligent search for the culprit lesion in the iliac veins is in order.

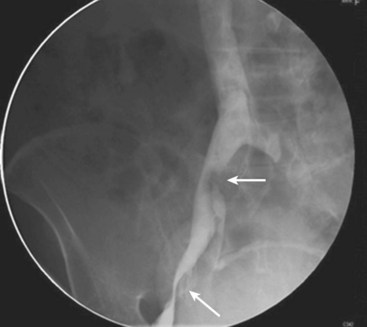

The discovery of a high incidence of NIVL in symptomatic CVD cases with IVUS and relief of symptoms with venous stenting has highlighted pathophysiologic peculiarities of these lesions. First, these lesions are widely prevalent in the asymptomatic population, with a gross prevalence of up to 30% in autopsy studies14 and up to 66% with more sensitive modern imaging techniques.15 With IVUS, the lesions are found in greater than 90% of patients with advanced symptoms.5 These are characteristics of permissive pathology, which is widely prevalent in human disease. Patent foramen ovale (PFO), with an incidence of approximately 25% in the asymptomatic general population, becomes symptomatic in a small fraction with onset of paradoxic embolus. Not surprisingly, PFO is invariably found in patients with paradoxic embolus. Other examples of permissive or secondary pathologies include obesity or diabetes, diabetes or neuropathy, carotid plaque or transient ischemic attack, ureteric reflux or pyelonephritis, Helicobacter pylori or peptic ulcer, and acid reflux or asthma. In case of silent iliac vein obstructions, a number of secondary events may trigger onset of symptoms (Box 50-1). A postthrombotic iliac vein lesion related to a remote thrombotic event can also remain silent for years or decades before symptoms are precipitated by a later trigger event (Figure 50-3). A general principle in treating these complex pathologies is to address the permissive pathology first, which usually provides definitive cure. The experience with iliac vein obstructions has been similar. In cases of combined obstruction and reflux, iliac vein stenting alone has provided effective symptom remission even when associated reflux was quite severe and remained untreated.6 In an analysis of 528 limbs that underwent iliac vein stenting for obstruction, severe reflux (reflux segment score ≥3) was present in 58% and axial reflux in 42% that remained uncorrected. Cumulative ulcer healing and clearance of dermatitis were 54% and 81%, respectively, at 5 years. No difference was noted between limbs with severe residual reflux and limbs with no reflux or less severe reflux. Venous pathologies uniquely respond to partial correction with symptom remission. For example, in combined superficial and deep reflux, correction of superficial reflux alone may provide symptom relief. In axial reflux, repair of a single valve may suffice.16 Valve reconstruction of a refluxive valve below an obstructed venous segment has been shown to be effective.17 With the advent of stent technology, repair of obstruction has become much easier than correction of reflux, which still requires open surgery. The satisfactory therapeutic response to partial pathologic correction means that a stepwise treatment paradigm starting with the simplest and minimally invasive techniques can be pursued; more complex or open treatment modalities can be reserved until later if there is recurrence of symptoms. The satisfactory clinical relief obtained with correction of chronic venous obstruction has suggested that in terms of pathophysiology, obstruction is as important as reflux, which has been the focus for the last 3 centuries.18 IVUS-proven iliac vein obstruction occurs in isolation without associated reflux in 27% to 36% of CVD patients with advanced symptoms.5,6 Venous ulceration appears to occur most commonly with combined obstruction and reflux, and only rarely with a single pathology of either obstruction or reflux.

Box 50-1

Secondary Insults That May Precipitate Symptoms in the Presence of a Silent Iliac Vein Lesion

There is an intimate relationship between venous and lymphatic systems in genesis as well as function. Lymphatic dysfunction can be demonstrated in approximately 30% of patients with advanced CVD.19 Lymphoscintigraphic delay in node visualization appears to be a defect in the precollectors at the microcirculatory level; the form and function of large collector lymphatics are apparently preserved. The precise nature of the damage to the precollectors is unknown, but is presumed to be related to the overloaded lymphatic transport imposed by venous dysfunction.

Clinical Features

Iliac vein thrombosis is a special form that can propagate distally, prompted by an underlying NIVL-type lesion.20 Recurrent venous thrombosis is a recognized cause of onset of symptoms in postthrombotic syndrome.21 The etiology of iliac vein obstruction (i.e., NIVL vs. postthrombotic) cannot be determined in most cases by clinical features alone, except when there is a clear history of prior deep venous thrombosis.

Investigations

Standard investigative techniques have poor sensitivity to iliac vein obstruction. Routine duplex technique does not provide adequate color flow images of the iliac vein. A new technique described by Labropoulos and colleagues22 offers better visualization and velocity metrics, but its accuracy has not been determined. Presence of reflux, even severe reflux (multisegment or axial), does not rule out the presence of iliac vein obstruction or the opportunity for symptom remission with stent correction, as already outlined. Absence of reflux or trivial reflux (reflux in only one or two segments, nonaxial reflux, or reflux in a small saphenous vein) in the context of severe presentation does suggest iliac vein obstruction. It is well established that routine venography, even through the transfemoral route, is only approximately 50% sensitive to iliac vein obstructive lesions in frontal projections.6 The accuracy of modern imaging techniques such as high-resolution computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging in detecting iliac vein lesions remains undetermined. No hemodynamic tests have adequate sensitivity to detect iliac vein obstruction. Exercise femoral vein pressures, outflow fraction measurement and arm/foot pressure measurement can be useful when positive, but do not rule out obstruction because of their low sensitivity. Using a combination of these techniques and transfemoral venography, it is possible to predict the presence of an iliac vein obstruction with approximately 80% accuracy.6 IVUS examination, a morphologic method, remains the most reliable technique in detecting iliac vein obstruction at present.23 Because of the high diagnostic yield with this method in symptomatic patients, it remains the preferred diagnostic modality at the present time. Stent correction of the detected stenosis can be performed concurrently with prior consent.