Thoracic Outlet Procedures: Transaxillary Approach

Dean J. Arnaoutakis

Julie A. Freischlag

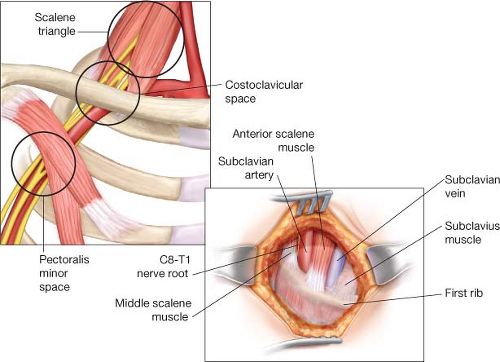

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is the modern term devised by Peet in 1956 to describe a constellation of symptoms and signs resulting from intrinsic or extrinsic injury to the neurovascular bundle in the thoracic outlet. The thoracic outlet is an area composed of three spaces: The scalene triangle, the costoclavicular space, and the pectoralis minor space (Fig. 22.1). The borders of the scalene triangle include the anterior scalene, middle scalene, and first rib. The neurovascular bundle, consisting of the brachial plexus, subclavian vein, and subclavian artery, exits the chest through the thoracic outlet (Fig. 22.1, inset). The subclavian vein actually does not travel through the scalene triangle since it lies anterior to the anterior scalene muscle. The narrow aspect of the thoracic outlet along with congenital musculoskeletal anomalies and daily life activities predispose the neurovascular bundle to injury. The most common bony abnormalities related to TOS include cervical ribs and anomalous first ribs. Cervical ribs, which are present in 0.7% of the population, arise from the transverse process of C7 and reside within the middle scalene muscle causing the scalene triangle to be an even tighter space. Each component of the bundle—the brachial plexus, subclavian vein, and subclavian artery—can be compressed giving rise to the three respective subtypes of TOS: Neurogenic TOS, venous TOS, and arterial TOS.

Indications

Surgical decompression of the thoracic outlet is necessary for patients with a diagnosis of TOS who have failed conservative management. Many surgeons prefer the transaxillary approach because of its relative ease, excellent cosmesis, and durable results. Specific indications for surgery depend on the TOS subtype.

Neurogenic TOS is the most common form of TOS accounting for approximately 95% of cases. The most common causes of neurogenic TOS include neck trauma involving a hyperextension neck injury (i.e., whiplash) or repetitive strain injuries at work. Anatomic structures previously mentioned are predisposing factors to the development of TOS. Hyperextension or repetitive strain to the anterior scalene muscle likely leads to chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and stricture of the muscle that can ultimately cause

compression and irritation to the brachial plexus. Affected patients, who are typically young women, complain of unilateral paresthesia, pain, and weakness throughout the hand and arm which do not follow a specific nerve distribution. These symptoms often extend toward the shoulder, upper back, and neck producing occipital headaches. On physical examination, symptoms are often reproducible upon palpation of various “trigger points” along the scalene triangle. The elevated arm stress test (EAST) is perhaps the most helpful maneuver in diagnosing neurogenic TOS. During this test, the patient raises both arms directly above the head and repeatedly opens and closes the fists. A patient with neurogenic TOS typically will develop arm pain and paresthesia within 60 seconds of starting this exercise. The initial treatment of neurogenic TOS is physical therapy directed at correcting posture and disordered movement patterns along with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and muscle relaxants. Conservative treatment is successful in up to 60% of patients. Surgery is reserved for those patients who fail an 8-week trial of these conservative measures.

compression and irritation to the brachial plexus. Affected patients, who are typically young women, complain of unilateral paresthesia, pain, and weakness throughout the hand and arm which do not follow a specific nerve distribution. These symptoms often extend toward the shoulder, upper back, and neck producing occipital headaches. On physical examination, symptoms are often reproducible upon palpation of various “trigger points” along the scalene triangle. The elevated arm stress test (EAST) is perhaps the most helpful maneuver in diagnosing neurogenic TOS. During this test, the patient raises both arms directly above the head and repeatedly opens and closes the fists. A patient with neurogenic TOS typically will develop arm pain and paresthesia within 60 seconds of starting this exercise. The initial treatment of neurogenic TOS is physical therapy directed at correcting posture and disordered movement patterns along with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and muscle relaxants. Conservative treatment is successful in up to 60% of patients. Surgery is reserved for those patients who fail an 8-week trial of these conservative measures.

Venous TOS accounts for about 5% of all cases and is usually due to repetitive, vigorous overhead arm activities and developmental anomalies of the costoclavicular space resulting in occlusion of the subclavian–axillary vein. The first rib and clavicle as well as the subclavius and anterior scalene muscles contribute to extrinsic mechanical compression of and repetitive injury to the subclavian vein. Patients with this “effort thrombosis,” referred to as Paget-Schroetter syndrome, are traditionally young, healthy men who present with acute edema, cyanosis, and dull pain of the affected (often dominant) upper extremity. However, in our practice, nearly half of all patients are women reflecting an increase in participation in sports and weight training. Some patients can have a more insidious process as they present with intermittent swelling which is due to chronic subclavian vein thrombosis or stenosis. Historically, patients were treated with anticoagulation alone but this resulted in very high residual functional impairment rates. The advent of catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy in the 1970s dramatically improved restoration of venous luminal patency; however, a substantial portion of patients developed recurrent thrombosis within 30 days due to uncorrected extrinsic compression. As such, early or immediate surgical decompression of the thoracic outlet following thrombolytic therapy is routinely performed in patients with venous TOS in order to minimize both symptoms and reocclusion rates. Of note,

simple anticoagulation can be effectively used instead of thrombolytic therapy prior to first rib resection. In a retrospective review from our institution, there was no difference in vein patency rates at 1 year between preoperative anticoagulation and thrombolysis.

simple anticoagulation can be effectively used instead of thrombolytic therapy prior to first rib resection. In a retrospective review from our institution, there was no difference in vein patency rates at 1 year between preoperative anticoagulation and thrombolysis.

Arterial TOS is the least common form of TOS accounting for less than 1% of patients but is a very serious entity requiring surgical intervention. Pathophysiology most commonly relates to the presence of a short, broad cervical rib that compresses the subclavian artery against the anterior scalene muscle resulting in chronic stenosis. Over time, the subclavian artery develops poststenotic dilatation which can progress to aneurysmal degeneration with secondary thrombosis or distal embolization. Although many are asymptomatic, patients with arterial TOS can present with critical hand and digit ischemia from microembolization to mild exertional arm claudication. On examination, a pulsatile supraclavicular mass or bruit can be detected with shoulder abduction. The Adson test, although not perfect due to its high false-positive rate, can be helpful. A positive test occurs when there is a reduction in the radial pulse after the patient takes a long breath in, elevates his chin, and turns it to the affected side. Surgical intervention aimed at arterial decompression, removal of the embolic source, and distal reperfusion is warranted for all symptomatic patients with ischemia and for asymptomatic patients with documented aneurysmal changes or intimal damage. Both a cervical rib and first rib can be successfully removed through a transaxillary approach so long as the subclavian artery has no evidence of aneurysm or thrombus as these findings would require a supraclavicular approach for arterial repair or bypass grafting.

Contraindications

No absolute contraindication to thoracic outlet decompression via a transaxillary approach exists; however, the transaxillary approach should be avoided in patients with arterial TOS who need vascular reconstruction, given the limited exposure of the subclavian artery with this approach. Also, patients with recurrent symptoms and evidence of residual first rib despite previous transaxillary first rib resection should undergo reoperative resection through a supraclavicular approach. As per routine, all comorbidities need to be identified, corrected, and/or compensated preoperatively, thereby minimizing the risks of general anesthesia. Perhaps more importantly, TOS can be difficult to diagnose because symptoms and signs are often vague and overlapping. Accordingly, ensuring that the patient has been correctly diagnosed with TOS is paramount for a successful operative outcome.

In addition to a focused history and physical examination, chest radiographs with cervical spine views are typically ordered for all patients suspected to have TOS. The radiograph can help identify skeletal pathology such as cervical ribs and elongated transverse cervical processes. Several other preoperative studies can aid in the diagnosis of TOS and its various subtypes.

For neurogenic TOS, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electromyography (EMG), and nerve conduction studies (NCS) are often obtained preoperatively, particularly in older patients with an atypical presentation. These studies are usually normal or nonspecific; nonetheless, they are helpful in excluding other conditions like degenerative cervical disk or spine disease, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, fibromyalgia, rotator cuff tendonitis, or carpal tunnel syndrome that could cause upper extremity symptoms. Vascular laboratory studies can reveal venous or arterial compression even in those with neurogenic symptoms alone. Angiography is rarely indicated. Scalene muscle block with CT- or ultrasound-guided injection of local anesthetic into the anterior scalene is perhaps the most useful preoperative study as relief of symptoms following the procedure helps confirm the diagnosis of neurogenic TOS. In fact, a strong correlation exists between symptom improvement following neuromuscular block and success with operative decompression, thereby reassuring the patient

and the physician of the expected outcome. Some have expanded upon these findings by locally injecting botulinum toxin into the anterior scalene providing symptom relief for up to 3 months. Botox injection can be safely repeated once since scar tissue usually forms making the intervention not as effective with multiple injections. As previously mentioned, patient enrollment in physical therapy is critical prior to operative intervention for neurogenic TOS.

and the physician of the expected outcome. Some have expanded upon these findings by locally injecting botulinum toxin into the anterior scalene providing symptom relief for up to 3 months. Botox injection can be safely repeated once since scar tissue usually forms making the intervention not as effective with multiple injections. As previously mentioned, patient enrollment in physical therapy is critical prior to operative intervention for neurogenic TOS.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree