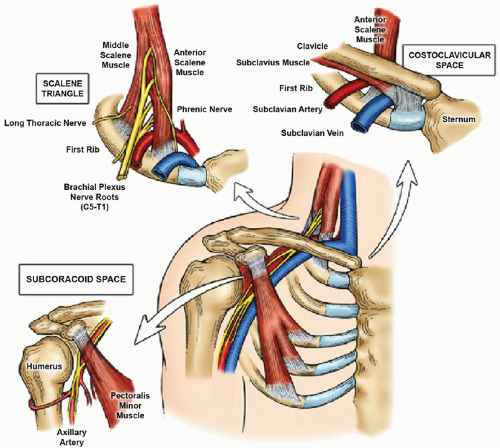

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a group of conditions caused by compression of the neurovascular structures that serve the upper extremity as they pass through the lower part of the neck, behind the clavicle, and over the first rib (

Fig. 24.1). The clinical presentation of TOS depends on the specific structures compressed, giving rise to three distinct conditions: (1)

Neurogenic TOS (NTOS), caused by compression and irritation of the brachial plexus nerves; (2)

Venous TOS (VTOS), caused by compression of the subclavian vein leading to venous thrombosis; and (3)

Arterial TOS (ATOS), caused by compression of the subclavian artery, leading to degenerative changes and thromboembolism. Although all three types of TOS are considered to be relatively uncommon, clinical recognition and appropriate treatment of these conditions is crucial to prevent disability in young active individuals.

NEUROGENIC THORACIC OUTLET SYNDROME

NTOS is the most frequent form of thoracic outlet compression, occurring in 85% to 90% of patients. It is due to compression and irritation of the brachial plexus nerve roots within the scalene triangle or underneath the pectoralis minor muscle tendon in the subcoracoid space. NTOS is considered to be caused by a combination of variations in anatomy (such as anomalous scalene musculature, aberrant fibrofascial bands, or cervical ribs) and previous neck or upper extremity injury that has resulted in scalene or pectoralis minor muscle spasm, fibrosis, and other pathologic changes. These muscular alterations, in turn, lead to compression and irritation of the adjacent brachial plexus nerves.

Brachial plexus nerve root compression can result in diverse symptoms that usually include pain, numbness, and tingling (paresthesia) in the neck, shoulder, arm, and hand. The intensity of these symptoms can vary, depending on levels of upper extremity activity, and are typically exacerbated with position, especially arm abduction and elevation. Although many patients with NTOS have relatively mild symptoms, with a slow gradual progression interspersed by occasional exacerbations, some exhibit a steady progression in the severity of symptoms leading to increasing and significant disability.

The diagnosis of NTOS is based on clinical evaluation, with supplemental testing procedures to exclude alternative or coexisting conditions (

Table 24.1). On physical examination there is usually welllocalized tenderness to palpation over the supraclavicular scalene triangle and/or the infraclavicular subcoracoid space, usually associated with reproduction of upper extremity symptoms. Most patients with NTOS report a rapid reproduction of upper extremity symptoms with provocative positional maneuvers, such as the upper limb tension test (ULTT) or the 3-minute elevated arm stress test (3-min EAST). Physical examination of patients suspected to have NTOS should also exclude any evidence of arterial or venous compromise to the upper extremity. Plain anteroposterior chest radiographs are useful to determine the presence or absence of a cervical rib, but other imaging studies of the brachial plexus are not specifically helpful in diagnosis. Conventional electrophysiologic testing (electromyography and nerve conduction studies) is often performed to exclude peripheral nerve compression disorders or cervical radiculopathy, but these tests are usually negative or nonspecific in NTOS. Image-guided anterior scalene muscle and/or pectoralis minor muscle blocks with a short-acting local anesthetic can provide support for the clinical diagnosis of NTOS, as well as help predict the reversibility of symptoms with treatment.

Initial treatment for NTOS is based on physical therapy to relieve muscle spasm, improve postural disturbances, enhance functional limb mobility, strengthen associated shoulder girdle musculature, and diminish repetitive strain exposure in the workplace. Incorrect approaches to physical therapy can result in worsening of symptoms and premature failure of conservative management. In most patients with mild NTOS or symptoms of short duration, significant improvement is observed within the initial 4 to 6 weeks and therapy is then continued on an “as needed” basis. Because NTOS is often a chronic condition subject to occasional “flare-ups” of acute symptoms (often related to overuse activities or new injury), the patient should continue regular physical therapy exercises during long-term follow-up.

Surgical treatment is recommended for patients with NTOS when the clinical diagnosis is sound, the patient has substantial disability (symptoms interfere with daily activities and/or work), and there has been an insufficient response to an appropriate course of physical therapy. Surgical treatment may also be recommended in selected patients with persistent or recurrent symptoms of NTOS following a previous operation, when there has been no response to appropriate conservative measures. Thoracic outlet decompression for NTOS may be accomplished by transaxillary operations focused on first rib resection, or by supraclavicular operations that include scalenectomy, first rib resection, and brachial plexus neurolysis. For patients with symptoms of NTOS referable to the subcoracoid space, surgical decompression may include pectoralis minor tenotomy as an addition to transaxillary or supraclavicular thoracic outlet decompression, or as an isolated procedure when this site is the dominant location of nerve compression symptoms.

VENOUS TOS

VTOS is characterized by subclavian vein compression between the clavicle, subclavius muscle, costoclavicular ligament, and first rib. The pathogenesis of VTOS involves repetitive extrinsic compression of the subclavian vein during activities involving arm

elevation or exertion, leading in time to chronic focal venous injury and progressive fibrous stenosis due to scar tissue formation and contraction around the outside of the vein, as well as fibrosis and wall thickening within the wall of the vein itself.

The initial phase of VTOS is usually asymptomatic, due to simultaneous expansion of collateral veins passing around the narrowed subclavian vein, but stagnant blood within the damaged segment of the subclavian vein eventually leads to thrombotic occlusion. Growth and peripheral extension of this clot into the axillary vein can further obstruct critical collateral veins, resulting in the acute clinical presentation characterized as axillary-subclavian vein “effort thrombosis” (Paget-Schroetter syndrome). Patients with subclavian vein effort thrombosis typically present with abrupt spontaneous swelling of the entire arm, often with cyanotic (bluish) discoloration, heaviness, and aching pain. Unlike more common forms of deep venous thrombosis (DVT), VTOS tends to occur in young, active, and otherwise healthy individuals, with no underlying blood clotting disorder. Pulmonary embolism from clot within the proximal subclavian vein may also occur, particularly with motion of the arm, but this is infrequent compared to DVT in the lower extremities.

The stereotypical clinical presentation of axillary-subclavian vein effort thrombosis is usually sufficient to establish the diagnosis of VTOS. Although venous duplex studies of the upper extremity may be used to confirm the presence of DVT, duplex imaging of the subclavian vein is inaccurate and cannot be used to exclude the diagnosis. In contrast, imaging studies such as magnetic resonance angiography or catheter-based venography provide more definitive information on the location and extent of axillary-subclavian vein thrombosis, and can be performed with the arms in elevation when there is incomplete subclavian vein obstruction. The distinct advantage of using catheterbased venography as the initial diagnostic step is that this can be followed immediately by thrombolytic therapy, which is often considered the first step in treatment. It is important to note that while blood coagulation testing is often performed in patients with upper extremity DVT, these tests are usually negative in those with VTOS and add little to the initial diagnosis or management.

Following the diagnosis of subclavian vein effort thrombosis by contrast venography, catheter-based thrombolytic therapy is recommended to reduce the amount of thrombus within the axillary and subclavian veins. In recent years this has been facilitated by pharmacomechanical approaches, where thrombolysis can usually be accomplished in a single setting. In most cases this results in a rapid reduction in the burden and extent of thrombus, and reveals a residual high-grade focal stenosis or occlusion of the subclavian vein at the level of the first rib. Balloon angioplasty may be used to reduce the degree of residual stenosis, but this is often unsuccessful at overcoming extrinsic bony compression or scar tissue within the wall of the vein. Over the past decade it has also become increasingly clear that placement of stents within the subclavian vein frequently leads to poor outcomes and should therefore be avoided. Following catheter-based venography and thrombolysis, patients with VTOS are maintained on therapeutic anticoagulation while considering further treatment options.

One option for treatment of VTOS consists of conservative treatment with chronic anticoagulation and long-term restrictions in arm activity, in the hope that recurrent venous thrombosis will not occur and that increased collateral development will eventually compensate for any residual axillary-subclavian vein obstruction. Even with satisfactory anticoagulation this approach is associated with recurrent thrombosis or chronic venous congestion in 50% to 70% of patients, and there is no information available on the optimal duration of anticoagulation for this condition. Lifelong anticoagulation and aggravation of symptoms during active use of the arm may also require considerable limitations, which are usually unacceptable for young active patients.

Surgical treatment is recommended within several weeks for almost all patients with VTOS, both to avoid long-term disability from venous obstruction and the need for long-term anticoagulation, and to permit a prompt return to normal activities. Surgical treatment is also recommended in patients with previous axillary-subclavian vein thrombosis that have remained symptomatic despite anticoagulation and restricted activity, as well as for asymptomatic individuals in whom long-term anticoagulation and restrictions on upper extremity activity are undesirable.

ARTERIAL TOS

ATOS is caused by subclavian artery compression within the scalene triangle, leading to the development of fixed subclavian artery stenosis, occlusion, or poststenotic subclavian artery aneurysms. ATOS almost always occurs in association with a congenital cervical rib or other bony anomaly. The development of subclavian artery surface ulceration or aneurysmal dilatation is often accompanied by mural thrombus formation, which frequently leads to distal thromboembolism with hand and/or digital ischemia. A second form of ATOS is observed in overhead throwing athletes, associated with occlusive or aneurysmal lesions of the distal axillary artery. These lesions are caused by repetitive trauma from hyperextension during the throwing motion, in which the axillary artery is compressed by forward motion of the head of the humerus. The thromboembolic complications of these lesions are similar to those of ATOS caused by subclavian artery lesions at the level of the first rib.

Patients with ATOS often present with acute thromboembolism in the upper extremity, characterized by the sudden onset of hand pain and weakness, numbness and tingling, and cold and pale fingers. Patients with more longstanding ischemia may present with chronic arm fatigue or claudication, nonhealing wounds, or ulcerations in the fingers. Subclavian artery occlusions or aneurysms may also be asymptomatic, with occlusions identified by a significant blood pressure differential between arms and aneurysms presenting as a nontender pulsatile mass in the lateral neck.

ATOS is usually readily suspected by clinical findings. The diagnosis may be confirmed by noninvasive vascular laboratory studies, such as duplex imaging and segmental arterial waveform analysis. Plain radiographs are important to determine if a cervical rib or first rib anomaly is present. Positional angiography (with either contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, or catheter-based arteriography) is typically performed to determine the presence or absence of a subclavian artery aneurysm. Similar imaging studies are performed in patients that have presented with upper extremity arterial thromboembolism to determine if a proximal source of embolism exists in the subclavian or axillary artery.

Immediate anticoagulation and urgent surgical treatment is recommended in patients with ATOS and acute upper extremity ischemia due to thromboembolism. Initial treatment may involve brachial artery exposure and thromboembolectomy to improve the distal circulation in the hand, with or without intraarterial infusion of thrombolytic and vasodilator agents. Treatment of the distal circulation should be immediately followed by thorough arteriographic assessment of the axillary and subclavian arteries, to establish a proximal source of thromboembolism, followed by thoracic outlet decompression and arterial reconstruction. For patients with stable distal circulation found to have ATOS, direct elective surgical treatment is recommended. Therapeutic anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy are continued in all patients from the time of diagnosis until definitive surgical treatment.