Thoracic Incisions

Matthew G. Blum

Willard A. Fry

Selection of the appropriate approach for thoracic procedures is critical to undertaking safe, effective operations. Incorrect incision choice with resultant inadequate exposure may lead to an unnecessary or difficult, ineffective operation or even fatal intraoperative complications. Thoracic surgeons need to be familiar with the advantages and disadvantages of many different incisions (see Table 25-1). With the availability of computed tomography (CT) scans, potential intraoperative anatomic issues can be contemplated in advance, so that the planning phase can include alternative incisions or extensions to the initial approach if necessary. This is especially true in the era of minimally invasive operation, when a secondary or tertiary incision may be necessary if the goals of the operation cannot be met using a minimally invasive approach. Additionally, some operations will require two incisions to achieve repair or resection safely. Finally, a thorough understanding of the relationships of intrathoracic structures to the external landmarks, muscles, and skeleton will allow creative, precise approaches for unusual pathology.

Positioning and Prophylaxis

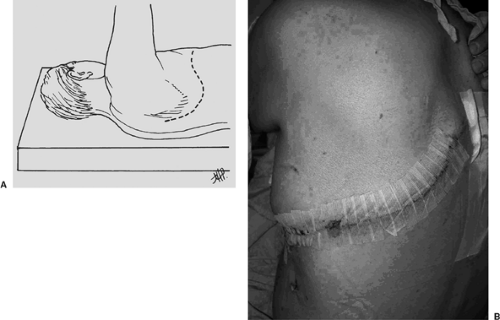

Most general thoracic surgical procedures are done with patients in the lateral decubitus position. Positioning injuries due to nerve stretching or compression at pressure points are a potential hazard, as the patient does not position himself or herself. Pressure points should be padded about the elbows using foam pads. Although technically supporting the chest wall, an “axillary” roll should be placed under the dependent chest wall to take pressure off the shoulder and brachial plexus. It is positioned caudal to the axilla so that fingers can easily be passed between the axilla and the chest roll. One or two pillows should be placed between the legs. The dependent tibial tuberosity and lateral malleolus should be padded (Fig. 25-1A,B). Various maneuvers are available to hold the patient in an appropriate lateral position, including placing a sandbag under the operating table mattress, rolled sheets front and back, and bean bags. Two straps of 3-in adhesive tape placed over surgical towels at the hip and the calf are used as well. The dependent arm is flexed at the elbow and padded. The superior arm can be flexed similarly and appropriately padded, obtaining the so-called praying position, or it can be extended on a padded Mayo stand or arm holder (Fig. 25-1A,B).

Prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis—including special elastic hose and a sequential compression device—is implemented prior to induction of anesthesia. The perioperative use of prophylactic heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin should be routine.

For most major general thoracic surgical procedures, the administration of prophylactic perioperative antibiotics is indicated to minimize wound infection. A few randomized trials of intravenous antibiotics specifically enrolling general thoracic surgical patients have been undertaken over the past several decades. Most showed reductions in the incidence of wound infections, although several did not reach significance.1 Antibiotic prophylaxis should be given prior to skin incision and redosed as necessary to maintain adequate levels throughout the operation. In accord with the Centers for Disease Control recommendations, systemic antibiotics should be discontinued after operation.

Staphylococcus aureus is a major nosocomial pathogen and colonizes the nares of up to 30% of the population. Preoperative treatment of patients who are carriers with 5 days of twice daily intranasal mupirocin has been shown to decrease S. aureus infections in carriers.18 A retrospective series with sequential groups of patients undergoing Ivor Lewis esophagectomy suggests that mupirocin may help decrease infectious complications and length of stay in this group.22

Posterolateral Thoracotomy

The main advantage of the posterolateral thoracotomy is the superb exposure for most general thoracic procedures. The main disadvantages are the time expended because of the length of the incision and the amount of muscle and soft tissue transected. Additionally, if a muscle flap is required for a complication such as a bronchopleural fistula and empyema with a space, the previously transected latissimus is often unsatisfactory owing to lack of collateral blood supply.

The posterolateral thoracotomy incision is made with the patient in the lateral decubitus position with the arms in a “praying” position. The skin incision is placed to provide access to the appropriate interspace. Occasionlly it is helpful to outline the proposed incision with a felt-tipped marking pen. Most pulmonary operations are best performed through a fifth interspace incision. A similar skin incision can be used for access to the fourth through sixth interspaces. The extent of incision can be varied according to the procedure to be performed and required exposure. The classic incision starts in front of the anterior axillary line, curves two fingerbreadths under the tip of the scapula, and extends vertically on a line halfway between the posterior midline over the vertebral column and the medial edge of the scapula (Fig. 25-2A,B). It is usually not necessary to go farther cephalad than the level of the spine of the scapula.

The electrosurgical unit is used for hemostasis and musculofascial dissection. The lower portion of the trapezius muscle is divided and, in the same plane more anteriorly, the latissimus dorsi muscle is divided. More limited incisions may divide only a portion of the latissimus. Next, the lower portion of the rhomboid muscle, if the thoracotomy is high, and the fascia immediately posterior to the serratus muscle is incised. The serratus muscle is spared and retracted anteriorly.

The desired interspace is located by placing a large Richardson or scapula retractor beneath the scapula and passing the hand paraspinally toward the head. Sometimes, the first rib is obscured to easy palpation, but attachments of the serratus posterior superior muscle to the second rib serve as an added guide.

Rib sectioning at or anterior to the costovertebral angle is rarely necessary but may be helpful to improve posterior exposure and decrease the incidence of rib fracture (Fig. 25-3A). Typically only a small portion of subperiosteal rib needs to be resected to prevent overriding of the cut ends. Although some recommend division and ligation of the neurovascular bundle, it is not necessary. It is unusual to resect a long segment of rib for a routine thoracotomy, although it was frequently done in the past. For repeat thoracotomies, however, it may be helpful to resect a long rib segment subperiosteally and approach the pleural space through the bed of the resected rib, as extensive adhesions are often encountered on such reoperations, and the wider entry into the pleural space through the bed of a resected rib can be beneficial (Fig. 25-4A).

The intercostal muscle incision down to the parietal pleura is made carefully in the lower portion of the interspace to avoid injury to the neurovascular bundle. If a pedicled intercostal flap may be useful, it is created at this time. The surgeon pauses to see if the lung moves freely under the pleura. If it does move freely, few adhesions in the area of the interspace can be expected. If the lung does not move freely, the surgeon must anticipate a significant number of adhesions and the need to divide them with care, particularly when the operation is a repeat thoracotomy. A Tuffier- or Reinhoff-type rib spreader can be placed anteriorly to ensure a wide surgical field. For large patients or wide exposure, a large Finochietto-type rib spreader is inserted, placing the large superior blade behind the scapula. The rib spreader is opened slowly and in stages to minimize the chance of rib fracture. A Balfour retractor is placed along the axis of the ribs to retract muscle and soft tissue.

Closure of the incision is begun by inserting one or two chest tubes through a separate stab incision inferior to the skin incision in the anterior and midaxillary lines. The tract for the tube is tunneled for several centimeters to direct the tube, low and posterior for the back tube to drain fluid and high and anterior for the front tube to remove air. Tunneling the tube tract also reduces the chance for a pleurocutaneous fistula in the event that the tubes must remain in place for a long time, as in the case of a prolonged postoperative air leak. Generally, two tubes are used if a significant resection has been performed, as the operator can expect both air and fluid accumulation. In selected cases, such as local excision of a lung lesion when no air leak exists or an esophageal operation in which the lung has not been cut, a single tube suffices. The size of the chest

tube to be used depends on the preference of the operating surgeon, the size of the patient, and the nature of the particular operation. In general, it is not necessary to use tubes larger than 28 Fr, as larger tubes tend to be more uncomfortable, particularly in small patients with narrow rib spaces. Typically a 24-Fr posterior and 20-Fr anterior tube are used to drain air and fluid respectively. Patients requiring chest tube drainage for purulent collections, blood, or fibrinous material may require larger drainage tubes to prevent clogging. The chest tubes are secured at the skin with a heavy nonabsorbable suture (e.g., No. 1 polypropylene) and connected to an appropriate chest drainage system.

tube to be used depends on the preference of the operating surgeon, the size of the patient, and the nature of the particular operation. In general, it is not necessary to use tubes larger than 28 Fr, as larger tubes tend to be more uncomfortable, particularly in small patients with narrow rib spaces. Typically a 24-Fr posterior and 20-Fr anterior tube are used to drain air and fluid respectively. Patients requiring chest tube drainage for purulent collections, blood, or fibrinous material may require larger drainage tubes to prevent clogging. The chest tubes are secured at the skin with a heavy nonabsorbable suture (e.g., No. 1 polypropylene) and connected to an appropriate chest drainage system.

Postoperative pain is generally managed using patient-controlled continuous epidural analgesia (PCEA) for posterolateral and axillary thoracotomy patients. The epidural catheter is placed prior to induction so that test dosing can be used to confirm proper placement and function. A bolus can then be given prior to emergence to minimize immediate postoperative

pain. Generally a combination of a local anesthetic and an opiate is administered continuously with a patient-controlled pushbutton that will give a small bolus on demand.

pain. Generally a combination of a local anesthetic and an opiate is administered continuously with a patient-controlled pushbutton that will give a small bolus on demand.

In situations where PCEA is contraindicated or unavailable, a paravertebral catheter (PARA) with a continuous infusion of fentanyl (5 μg/mL) with bupivacaine 0.1% has been useful.5 Drug concentrations can be varied if side effects such as drowsiness and nausea occur. In the event that PCEA or PARA is not feasible, an intercostal nerve block with a long-acting local anesthetic such as 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine is placed prior to chest wall closure. The intravascular injection of such compounds can have dire cardiovascular consequences and should be avoided.8 The blocks should include at least two interspaces above and two below the thoracotomy as well as the chest tube insertion interspace(s). The subpleural injections are given at least 8 cm off the midline to avoid a subdural injection, which would produce spinal anesthesia. Intravenous patient-controlled analgesia is used to complement the rib block.

Pericostal sutures, usually three, of heavy absorbable material, such as No. 2 polyglycolic acid, are then placed. The rib spaces are reapproximated to their original position but not overcorrected, even if a rib is resected (Figs. 25-3B and 25-4B). Intracostal (also called transcostal) suture placement through holes drilled in the lower rib may minimize intercostal nerve injury and decrease postoperative pain.6,20 Each of the two musculofascial planes is closed with running suture of a similar material, usually size 1 or 0; the subcutaneous tissues are closed with a size 2-0 running suture of the same material and the skin with the surgeon’s preferred material.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree