Thoracic Approaches

M. Blair Marshall

The optimal approach to the thorax depends on a number of variables including bony and hilar anatomy, location and extent of pathology, the objectives of the procedure, and the experience of the surgeon. Historically, the posterolateral thoracotomy was the workhorse for the majority of major thoracic procedures, the majority of approaches to thoracic pathology were performed through this, and there was significant short-term and long-term morbidity associated with the operations we performed. Today, with advances in surgical techniques, emphasis on less invasive procedures, optimization of perioperative care, and approaches to thoracic pathology have become more diverse and specialized. In addition to the prerequisite factors required for planning an approach, one may also consider alternative strategies for the management of lung isolation, positioning, and the inherent limitations of the instrumentation or the additional time required to complete a minimally invasive or multi phased procedure.

Given the short-term morbidity as well as chronic pain associated with traditional approaches, alternative approaches are becoming routine. These approaches may favorably affect morbidity, operative time, postoperative pulmonary function, muscle strength, cost, and postoperative pain. Although the specific costs associated with a minimally invasive approach appear to be increased, these are offset by shortened time in intensive care units and decreased length of stay. In the future, less invasive, tissue-sparing approaches may also demonstrate additional benefits as it relates to oncologic outcomes. It is not clear if this is a benefit of the approach in relation to decreased tissue damage and decreased cytokine response versus improved recovery and a thus earlier initiation of adjuvant therapy. Given the limited access provided through these minimally invasive approaches, careful preoperative planning and operative steps and strategy should be routinely visualized prior to performing the operation. Anticipation of intraoperative steps and exposure will go a long way toward preventing misadventures during the surgical procedure.

LUNG ISOLATION

For traditional and minimally invasive approaches, lung isolation with a double-lumen endotracheal tube remains the key maneuver to facilitate working within the pleural cavity. Given the length of the left main stem bronchus, left-sided tubes are the preferred choice, except in the setting of a left-sided sleeve resection.

At times, lung isolation through a double-lumen tube may be unnecessary or problematic, as in patients with an end tracheal stoma. Alternative lung isolation strategies include placement of a bronchial blocker or direct compression of the lung with CO2 insufflation. When using a bronchial blocker, it is important to instruct the anesthesiologist to deflate the bronchial balloon and disconnect the ventilator. This will allow the ipsilateral lung to collapse more readily releasing any air that might be trapped behind the balloon.

Visualization within the pleural space may be facilitated with CO2 insufflation if a single-lumen endotracheal tube must be used. In this setting, unlike that of laparoscopic surgery, a pressure of 10 mmHg is sufficient to collapse the lung and obtain a working space. Pressures >10 mmHg are often poorly tolerated due to the creation of tension physiology. Lesions accessible with this type of approach are simple wedge resections, as well as anterior and posterior mediastinal lesions. However, this technique is not suitable for complex pulmonary resections or any other circumstance where the complexity would necessitate absolute control of ipsilateral ventilation.

When working within the diaphragmatic hiatus via a laparoscopic approach, inadvertent entry into the pleural space is not uncommon potentially creating tension physiology. If hypotension ensues, it can be resolved by decreasing the insufflation pressure to 10 mmHg.

POSITIONING

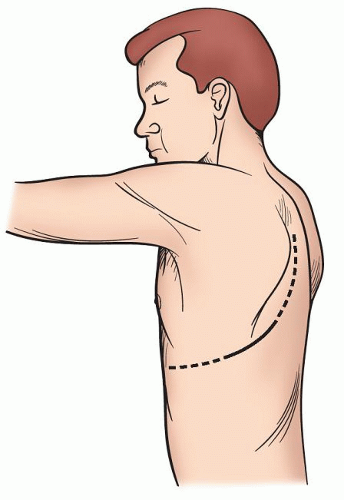

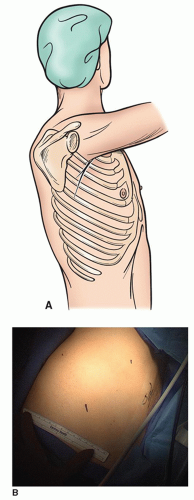

The lateral decubitus continues to be the mainstay for the management of the majority of pulmonary pathology (Fig. 3.1), but with increasing frequency alternative positions are used to manage lesions in the region of the posterior or anterior mediastinum. With axillary approaches and also our preference for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) lobectomy, the opposite shoulder is elevated with a roll to expose the anterior axillary line. This allows better direct exposure through the intercostal space and also allows one to move the edge of the latissimus to a more posterior position minimizing the need to divide even a portion of this muscle (Fig. 3.2).

With either of these positions, the hip is placed below the area of flexion in the bed so that this allows for a slight widening of the intercostal space. It is critical when performing a chest wall reconstruction with prosthesis that the table should be taken out of flexion prior to securing the mesh in place. If this step is omitted, the mesh will not be caught and may result in a flail segment.

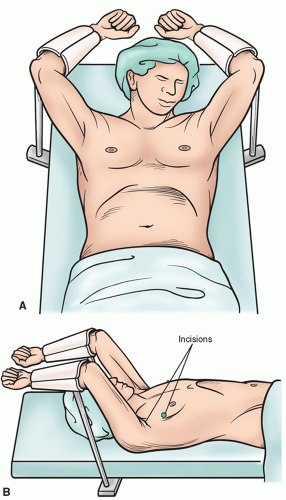

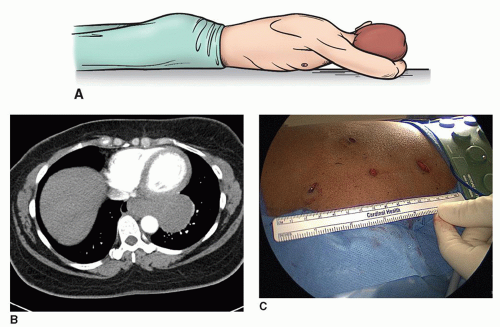

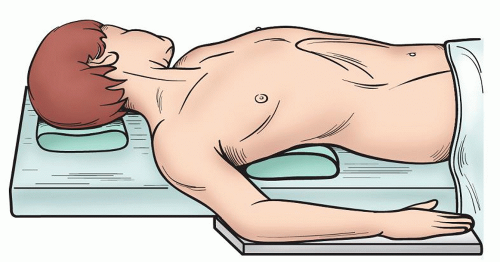

The semi-Fowler’s position with the arms supported at right angles allows one to access both sides of the chest without a need to reposition the patient, as for a bilateral thoracoscopic sympathectomy (Fig. 3.3A and 3.3B). Apical bullectomy and pleurodesis may also be done through this approach. For additional approaches to the posterior mediastinum, as in the thoracoscopic portion of a minimally invasive esophagectomy, the prone position allows for excellent visualization of the posterior mediastinum while allowing the airway and lungs to fall away from the esophagus. For this position, the patient’s arms are placed above his head so that the scapula is brought up as high as possible, minimizing interference with access to the chest. (Fig. 3.4A- 3.4C)

In contrast, access to the anterior mediastinum can be performed in the lateral decubitus as with traditional operations

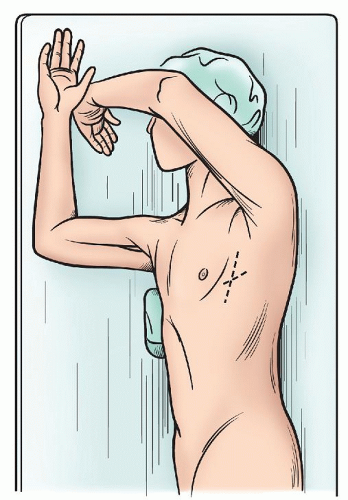

or in the supine or semi-supine position. The latter positioning allows for visualization of the contralateral side of the thymus when performing VATS resections. When utilizing such positioning, access to the lateral chest wall should be planned for in advance if a combined approach will be used. In this setting, we will usually place a roll under the side of the chest we wish to expose, and pull the arm and shoulder posterior so that the cervical as well as thoracoscopic approaches can be simultaneously used without the need to reposition (Fig. 3.5).

or in the supine or semi-supine position. The latter positioning allows for visualization of the contralateral side of the thymus when performing VATS resections. When utilizing such positioning, access to the lateral chest wall should be planned for in advance if a combined approach will be used. In this setting, we will usually place a roll under the side of the chest we wish to expose, and pull the arm and shoulder posterior so that the cervical as well as thoracoscopic approaches can be simultaneously used without the need to reposition (Fig. 3.5).

VIDEO-ASSISTED THORACOSCOPIC SURGERY APPROACHES

Historically, video thoracoscopic procedures started with simple thoracic procedures, and the ports were placed along the line of an anticipated thoracotomy incision. Currently, port positioning is more commonly chosen based on the objectives of the operation, and the limitations of the instrumentation as well as experience of the surgeon. The potential need to convert to an open procedure no longer is a major

consideration as ports have become much smaller and the need to convert to a standard posterolateral thoracotomy much less likely.

consideration as ports have become much smaller and the need to convert to a standard posterolateral thoracotomy much less likely.

Fig. 3.5. The patient is positioned semi-supine with a support under the chest. This allows the ipsilateral arm to fall posterior to minimize interference with instrumentation. |

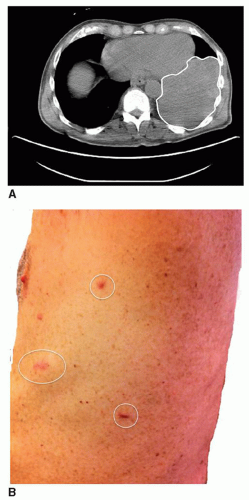

Today, the complexity of cases performed with this approach has increased significantly. Re-operations after previous thoracotomy, lobectomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection, thymectomy, and resection of mediastinal lesions are all performed under thoracoscopic guidance. In these settings, port sites are strategically located in order to minimize the challenges associated with instrumentation, the bony and hilar anatomy, as well as the pathology. Given this, one must alter port location, as well as patient positioning to facilitate not only exposure but also freedom of instrumentation. Although we typically use three-port sites, we will add a fourth when needed for more complex procedures. Upper extremity positioning or other hindrances may interfere with the full mobility of instruments, and these limitations should be anticipated when planning the operative procedure. In particular, when dealing with benign disease, where margins are less of a concern, a utility port is unnecessary as tumors may be morcellated prior to extraction (Fig. 3.6A and 3.6B).

Because the nuances associated with port positioning are critical to successful performance of the procedure, we will briefly discuss the minimally invasive approaches to specific pathology.

Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery Wedge Resection

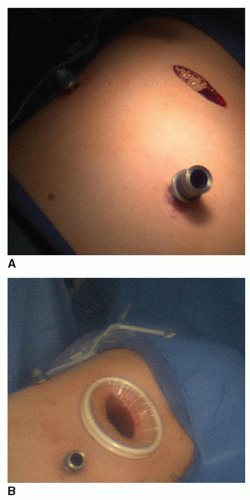

For any video-guided surgery, triangulation of port sites is essential to minimize instrument interference and improve visualization. Port placement is fairly standard with two usually placed along the anterior axillary line and one posterior below the tip of the scapula. We try to minimize the posterior location as the intercostal spaces are narrower and trauma to the intercostal nerve may be more likely to occur. However, if one is planning for a VATS wedge resection with subsequent lobectomy with lymph node dissection, it is important to locate the superior port along the planned incision for the utility port. In our experience,

we typically use two 5-mm ports for the superior ports and a 10-mm port for the inferior port along the anterior axillary line. The intercostal spaces are larger here to allow for placement of a stapler and this site functions as the subsequent chest tube site (Fig. 3.7A and 3.7B).

we typically use two 5-mm ports for the superior ports and a 10-mm port for the inferior port along the anterior axillary line. The intercostal spaces are larger here to allow for placement of a stapler and this site functions as the subsequent chest tube site (Fig. 3.7A and 3.7B).

For complex procedures, port site location is modified based on anatomic and clinical factors. One must identify where the target lesion is to be found. If direct palpation is necessary to identify the lesion, we typically place the larger port site specifically within “finger reach” of the target lesion. We tend to keep two-third of the port sites in the 5 mm range when possible. In this setting, it is only possible to palpate through one port or pass the stapler for a wedge excision through one port and the angle and trajectory that this port takes must be taken into account. Another critical factor is the width of the patient’s intercostal spaces, as the more posterior aspect of the space is significantly narrower. We do not hesitate to enlarge an incision when necessary or resect a small segment of rib to accommodate direct palpation when one cannot identify the lesion. For any thoracoscopic procedure, the surgeon should be positioned on the side of the camera to facilitate orientation with the projected image.

Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery Lobectomy

For a VATS lobectomy, when placing the port sites for the diagnostic portion and then proceeding with a lobectomy, the anterior-superior port site is placed overlying the superior pulmonary vein for an upper lobectomy and above the pulmonary artery within the fissure for a lower lobectomy, as this will become the location of the utility port. There is great variation among surgeons as to the optimal location of ports for VATS lobectomy. We typically use two incisions along the anterior axillary line, one for the utility port as described above and the inferior one at the seventh intercostal space for the camera. We use a second 5-mm port posteriorly approximate one inner space below the tip of the scapula. We tend to again manipulate the patient’s ipsilateral elbow to open up the axilla, as in an axillary thoracotomy, as this allows the utility port to be muscle sparing as the edge of the latissimus dorsi muscle is reflected posteriorly and the serratus anterior muscle is split along the intercostal space. We use a soft tissue retractor as it minimizes the potential trauma from metal retractors and the exposure it provides, especially in the larger patient, is unparalleled (Fig. 3.8A and 3.8B).

Although some thoracic surgeons perform the entire procedure without moving the camera position, we typically will place the camera through the posterior port site in order to perform the posterior dissection of the airway as well as to dissect the level 7 lymph nodes.

VIDEO-ASSISTED THORACOSCOPIC SURGERY APPROACH TO THE ANTERIOR MEDIASTINUM

For the VATS approach to anterior mediastinal lesions, location of port placement is dependent upon the overall strategy and position of the patient. We tend to use a semi-supine position and combine a transcervical thymectomy with a left-sided VATS for thymectomy as the aorto-pulmonarg window can be particularly challenging through a limited transcervical approach (Fig. 3.9). As well, for complex lesions or in the setting of mediastinal resection in patients who have undergone previous sternotomy, direct exposure is critical and we have found placement of a port in the infraclavicular fossa to be a useful position for access to the mediastinum. In this setting, the patient is either positioned supine or if in the lateral decubitus, the ipsilateral upper extremity is positioned posterior

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree