Chapter 59 The Diabetic Foot

Diabetes is a growing epidemic in the United States and around the world. The 2011 National Diabetes Fact Sheet estimates that 26 million children and adults in the United States have diabetes, representing 8% of the U.S. population. An additional 79 million have prediabetes but nevertheless may be susceptible to the full range of its complications. Diabetes complications, which include cardiac disease, stroke, hypertension, blindness, renal disease, neuropathy, and amputation, consume more than 30% of U.S. health care expenditures.1

Neuropathy

Peripheral neuropathy is one of the most common long-term complications of diabetes, affecting up to 50% of patients by the tenth year of the diagnosis. It typically manifests as a mixture of sensory, motor, and autonomic involvement. The pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy results from metabolic and vascular disorders that affect nerve blood flow and vascular endothelial function.2

A neurologic examination should be done to evaluate sensory and motor function in all patients with diabetes. Loss of protective sensation (LOPS) is a more severe form of diabetic neuropathy that increases the risk for ulceration. It is most readily revealed by applying pressure on selected dorsal and plantar areas of the foot with a deformable Semmes-Weinstein monofilament (SWMF) (Figure 59-1).2

If the patient is unable to feel 10 g of pressure exerted by a SWMF, they have met the criteria for LOPS. Patients should be screened annually for neuropathy. The nerve function profile of Boulton and colleagues provides a useful and reproducible baseline that has been validated as predictive of ulceration.3,4

Autonomic neuropathy interrupts control of arterial and capillary flow to the feet and tissues, resulting in decreased sudomotor function and dry feet, anhidrosis, noncompliant skin, and, ultimately, fissuring and painful cracking of the skin. Deep heel cracks and fissures are a common manifestation of autonomic neuropathy. This process results in an “auto-sympathectomy,” which explains why surgical ablation of the lumbar sympathetic trunk provides no benefit for diabetic ulceration. The stage is thus set for bacterial penetration and clinical infection. Autonomic control of vascular smooth muscle can also be affected, which leads to hyperemic states and possibly contributes to the development of Charcot destruction. The importance of neuropathy in diabetic foot ulceration is best encapsulated by the words of Dr. Paul Brand, considered “the patron saint of the diabetic foot.”4a He wisely observed: “If the patient walks into your clinic with a diabetic foot ulcer and does not limp, he has neuropathy. For that reason alone the doctor should always observe the patient as he/she walks.”

Ulceration

Evaluation

The evaluation should also identify common deformities and biomechanical abnormalities that contribute to the ulcer. For instance, ill-fitting footwear can cause ulcers to develop on the dorsum of toes, interdigitally, or on the lateral aspect of the foot. Ulcerations located on the dorsal aspect of toes may be related to contracted digits in a shallow toe box. Ankle equinus contracture, defined as ankle dorsiflexion of less than 10 degrees, causes increased pressure of the plantar forefoot and midfoot, leading to calluses and ulceration. Patients with amputations or shortened foot are susceptible to ankle equinus because the ankle flexors overpower the extensors (Figure 59-2).5

The Charcot foot rocker bottom deformity increases pressure at the apex of the deformity, usually at the midfoot, leading to mid-foot collapse and to the characteristic ulcer (Figures 59-3 and 59-4).

The plantar ulcerations that arise with increased ankle flexion and plantar pressure are not usually amenable to correction with footwear; the Achilles tendon is best dealt with by tendo-Achilles lengthening (TAL) or operative lengthening of the gastrocnemius muscle.6

Ulcer Classification

The established systems to stratify the severity of foot ulceration are based on the size of ulceration (area and volume), location, tissue loss, presence of infection, and the anatomic and hemodynamic state of the arterial circulation. Three diabetic ulcer classification systems are widely used: the University of Texas (UT) classification, PEDIS, and Wagner grading.7,8 The UT and PEDIS classifications were developed specifically for the diabetic foot. Wagner grades were first described for the foot known or presumed to be dysvascular but are now applied to all etiologies of lower extremity ulcerations.9 The UT system appears to be a better predictor of ultimate wound outcome, is often used in wound centers, and has been validated. The Wagner classification is based on the depth of penetration, the presence of osteomyelitis, or the extent of gangrene. A major shortcoming of Wagner grading is that the presence of ischemia is not specified in the consideration of the earlier stages. Because most ulcers fall into either grade I or II, the Wagner system inadequately differentiates the etiologic factors that underlie the majority of lesions. Finally, there is the (P)erfusion, (E)xtent, (D)epth, (I)nfection, (S)ensation or PEDIS classification developed by the International Consensus on the Diabetic Foot, which was devised initially as a research tool because of its relative complexity (Table 59-1).

TABLE 59-1 Table of Ulcer Classification Systems

Charcot Foot

Charcot neuroarthropathy was first described in tabes dorsalis in syphilis. It is now most commonly associated with diabetes but could occur as a result of any neuropathy.10 The International Task Force on the Charcot Foot stated the condition is primarily a disease of unopposed inflammation in the foot, leading to increased vascularity and bone resorption. It is a chronic and most often progressive disease of bone and joints. Common features include joint dislocation, pathologic fractures, and severe destruction of the pedal architecture, resulting in debilitating deformity, increased risk of ulceration, and increased risk for major amputation from complications of ulceration. It can lead to disability and premature retirement. The task force recommended classifying Charcot foot as active or inactive, depending on whether inflammation was present.11

The most important factor in early detection and the potential to alter the outcome of patients with Charcot foot comes from retaining a high clinical suspicion in patients with the important risk factors. It can be precipitated by seemingly minor trauma. The clinical signs most associated with the disease are an erythematous, hot, and edematous foot. When these clinical findings predominate, it is easy to understand why Charcot can be mistaken for, and is treated as, a deep infection. Approximately 50% of patients have pain with their Charcot foot, which complicates its diagnosis because it is a syndrome caused by neuropathy. The diagnosis is often missed and thus delayed. The characteristic rocker bottom deformity is a late sign of the disease.12

There is consensus that the cornerstone of management of acute Charcot foot is early immobilization and offloading. Judicious use of a total contact cast (TCC) or removable cast walker, crutches, walkers, knee walkers, wheelchairs, or bed rest may be appropriate in this setting (Figure 59-5).13,14

Ulcer Management

After adequate ulcer evaluation, wounds are managed with nonsurgical or surgical strategies.

Surgical

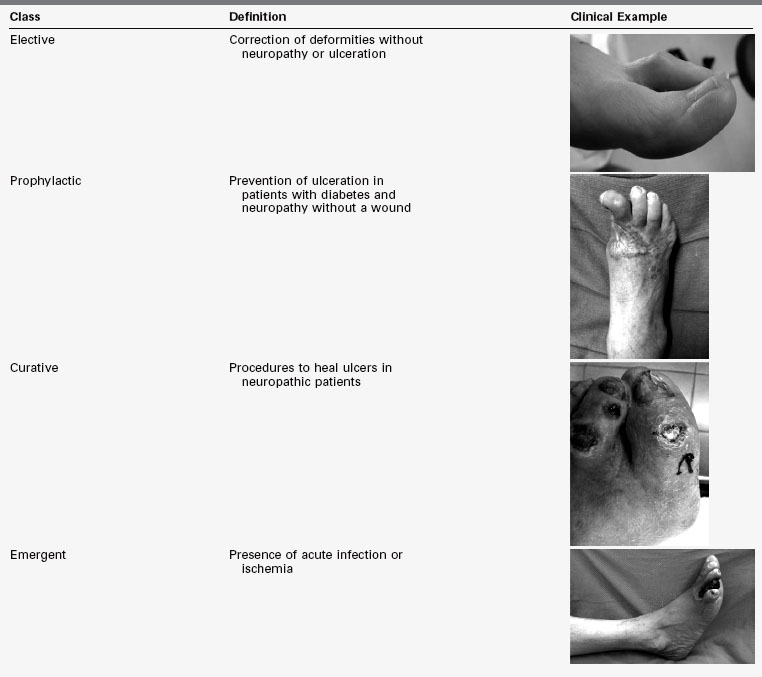

Diabetic foot surgical interventions fall into one of four classes: elective, prophylactic, curative, and emergent. Elective surgery is composed of procedures for deformities in the absence of neuropathy or ulcerations. Prophylactic surgery includes procedures for the prevention of ulceration in patients with diabetes and neuropathy, but without a wound. Curative procedures are used to heal ulcers in neuropathic diabetic patients. Emergent procedures are performed in the setting of acute infection or ischemia. The risk of postoperative infection increases as the classes progress from elective to emergent (Table 59-2).15

TABLE 59-2 Classes of Foot Surgery With Clinical Examples

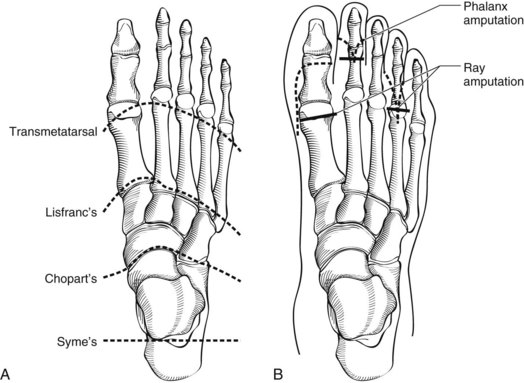

Forefoot amputations are desirable because they preserve length, which preserves maximal mobility and function; the transmetatarsal amputation (TMA) is a case in point. More proximal partial foot amputations such as at the Lisfranc joint or Chopart amputation at the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints require adjunctive procedures to maintain a balanced foot (Figures 59-6 and 59-7).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree