The Cardiomyopathies

CLASSIFICATION OF THE CARDIOMYOPATHIES

In 1995, a classification scheme for the cardiomyopathies was proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO). This scheme defined cardiomyopathies as ‘diseases of the myocardium associated with cardiac dysfunction’ and categorized them as follows:

dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)

restrictive cardiomyopathy

arrhythmogenic right ventricular (RV) cardiomyopathy

unclassified cardiomyopathies (e.g. isolated ventricular non-compaction).

The WHO classification also recognized an overlapping group of ‘specific’ cardiomyopathies, in which a particular case of cardiomyopathy could be attributed to a specific underlying aetiology. Examples include:

ischemic cardiomyopathy

valvular cardiomyopathy

hypertensive cardiomyopathy

metabolic cardiomyopathy

peripartum cardiomyopathy (Chapter 29).

The advent of molecular genetics has provided new insights into the pathophysiology of the cardiomyopathies, and in some respects the WHO classification is now somewhat outdated. In 2006, the American Heart Association (AHA) proposed a new scheme in which cardiomyopathies are defined as: ‘a heterogeneous group of diseases of the myocardium associated with mechanical and/or electrical dysfunction that usually (but not invariably) exhibit inappropriate ventricular hypertrophy or dilatation and are due to a variety of causes that frequently are genetic. Cardiomyopathies either are confined to the heart or are part of generalized systemic disorders, often leading to cardiovascular death or progressive heart failure-related disability.’

According to the AHA classification, cardiomyopathies can be classified as primary (mainly or only affecting the heart) or secondary (where the cardiomyopathy is part of a wider multisystem disorder):

primary cardiomyopathies

acquired (e.g. post-myocarditis, stress-related, peripartum, tachycardiainduced)

mixed (e.g. DCM, restrictive cardiomyopathy)

secondary cardiomyopathies

infiltrative (e.g. amyloidosis)

storage (e.g. haemochromatosis, Fabry’s disease)

toxicity (e.g. drugs)

endomyocardial (e.g. endomyocardial fibrosis)

inflammatory (e.g. sarcoidosis)

endocrine (e.g. diabetes mellitus, acromegaly)

cardiofacial (e.g. Noonan syndrome)

neuromuscular/neurological (e.g. Friedreich’s ataxia)

nutritional deficiencies (e.g. beriberi, scurvy)

autoimmune/collagen (e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus)

electrolyte imbalance

consequence of cancer therapy (e.g. anthracyclines).

The echo assessment of any cardiomyopathy requires a detailed study with a particular emphasis on chamber morphology, dimensions and function (including ventricular systolic and diastolic function), as outlined in Chapters 15-18 and 21, together with a full assessment of valvular function. In addition, you will need to look for the specific features relating to the cardiomyopathy in question. This chapter describes the key features of the cardiomyopathies most likely to be encountered in everyday practice.

DILATED CARDIOMYOPATHY

DCM is characterized by dilatation and systolic impairment of the left ventricle (LV), usually accompanied by dilatation of the RV and the atria. DCM can result from a number of conditions, including:

myocarditis

alcohol

prolonged tachycardia (tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy)

pregnancy (peripartum cardiomyopathy).

Familial DCM is also recognized, defined by the presence of DCM in two or more individuals in the same family. DCM is also seen in X-linked diseases such as Becker and Duchenne muscular dystrophies. DCM without an identifiable cause is called idiopathic DCM. LV dilatation and impairment secondary to ischaemic, valvular or hypertensive heart disease is not usually classified as DCM.

Echo features

The echo assessment of DCM includes a comprehensive assessment of:

LV dimensions and function (Chapters 15-17)

RV dimensions and function (Chapter 21)

left atrial (LA) dimensions (Chapter 18)

right atrial dimensions (Chapter 21)

valvular function (Chapters 19-21).

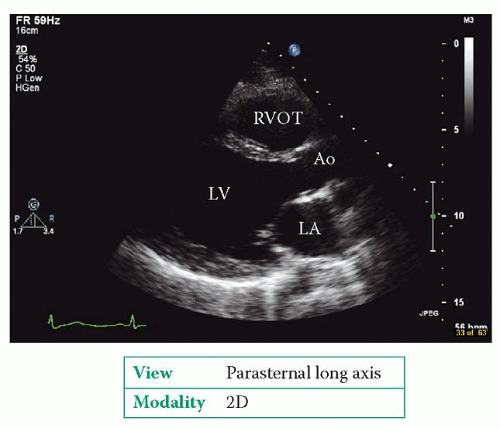

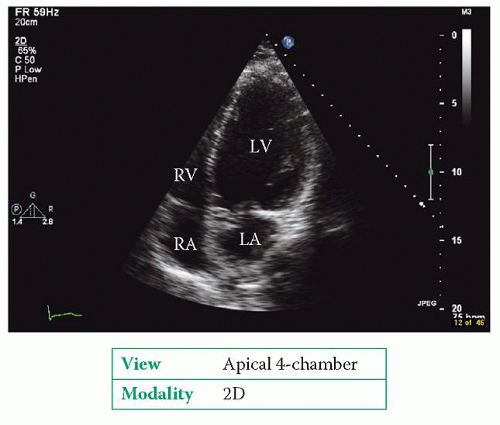

Examples of DCM are shown in Figures 24.1 and 24.2. The echo study usually cannot identify the aetiology of the DCM.

APICAL BALLOONING CARDIOMYOPATHY

A rare form of cardiomyopathy, first described in Japan, is apical ballooning or stress cardiomyopathy. It is also known as takotsubo (‘octopus bottle’) cardiomyopathy, named after the characteristic shape of the LV seen in this condition. This cardiomyopathy is most commonly seen in post-menopausal women and is triggered by extreme emotional or clinical stress, which causes a ballooning of the LV apex. Patients present with chest pain and/or heart failure with ECG changes suggestive of an anterior myocardial infarction (but in the absence of coronary artery disease). In most cases LV function recovers within 2 months of the presenting episode.

HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY

HCM is an autosomal dominant condition affecting 1 in 500 of the population and is a common cause of sudden cardiac death, particularly in the young. The LV

hypertrophy in HCM is usually (but not always) asymmetrical and systolic function is preserved but diastolic function is impaired.

hypertrophy in HCM is usually (but not always) asymmetrical and systolic function is preserved but diastolic function is impaired.

If the hypertrophy is located in the LV outflow tract (LVOT) it may obstruct the flow of blood out of the LV into the aorta – this is hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM). Another common pattern is apical hypertrophy, which gives the LV cavity a characteristic ‘ace of spades’ appearance.

Transthoracic echo is part of the initial evaluation of all patients with suspected HCM, and should be repeated in clinically stable patients every 1-2 years to assess LV hypertrophy, LV function and any dynamic obstruction. A change in clinical status should prompt an earlier follow-up echo study.

Echo should also be included in the screening of family members. Screening is recommended for all first-degree relatives of a patient with HCM.

Echo features