Chapter 51 The Appendix

Approximately 8% of those in Western countries have appendicitis at some time during their life, with a peak incidence between 10 and 30 years of age.1 Acute appendicitis is the most common general surgical emergency, and early surgical intervention improves outcomes. The diagnosis of appendicitis can be elusive, and a high index of suspicion is important in preventing serious complications from this disease. Worldwide, perforated appendicitis is the leading general surgical cause of death.

Embryology and Anatomy

The length of the appendix varies from 2 to 20 cm, and the average length is 9 cm in adults. The base of the appendix is located at the convergence of the taeniae along the inferior aspect of the cecum and this anatomic relationship facilitates identification of the appendix at operation. The tip of the appendix may lie in various locations. The most common location is retrocecal but within the peritoneal cavity. It is pelvic in 30% and retroperitoneal in 7% of the population.2 The varying location of the tip of the appendix likely explains the myriad of symptoms that are attributable to the inflamed appendix.

Appendicitis

Historical Perspective

In 1886, Reginald Fitz of Boston correctly identified the appendix as the primary cause of right lower quadrant inflammation. He coined the term appendicitis and recommended early surgical treatment of the disease. Richard Hall reported the first survival of a patient after removal of a perforated appendix, which focused attention on the surgical treatment of acute appendicitis. In 1889, Chester McBurney described characteristic migratory pain and localization of the pain along an oblique line from the anterior superior iliac spine to the umbilicus. McBurney described a right lower quadrant muscle-splitting incision for removal of the appendix in 1894. The mortality rate from appendicitis improved with the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics in the 1940s. Advances have included improved preoperative diagnostic studies, interventional radiologic procedures to drain established periappendiceal abscesses, and the use of laparoscopy to confirm the diagnosis and exclude other causes of abdominal pain. Laparoscopic appendectomy was first reported by the gynecologist Kurt Semm in 1982 but has only gained widespread acceptance during the past decade. Other minimally invasive approaches to appendectomy have been reported, including transvaginal3 and single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS)4; however, these have not as yet been widely adopted.

Pathophysiology

Obstruction of the lumen is believed to be the major cause of acute appendicitis.2 This may be caused by inspissated stool (fecalith or appendicolith), lymphoid hyperplasia, vegetable matter or seeds, parasites, or a neoplasm. The lumen of the appendix is small in relation to its length and this configuration may predispose to closed-loop obstruction. Obstruction of the appendiceal lumen contributes to bacterial overgrowth and continued secretion of mucus leads to intraluminal distention and increased wall pressure. Luminal distention produces the visceral pain sensation experienced by the patient as periumbilical pain. Subsequent impairment of lymphatic and venous drainage leads to mucosal ischemia. These findings in combination promote a localized inflammatory process that may progress to gangrene and perforation. Inflammation of the adjacent peritoneum gives rise to localized pain in the right lower quadrant. Although there is considerable variability, perforation typically occurs after at least 48 hours from the onset of symptoms and is accompanied by an abscess cavity walled off by the small intestine and omentum. Rarely, free perforation of the appendix into the peritoneal cavity occurs, which may be accompanied by peritonitis and septic shock and can be complicated by the subsequent formation of multiple intraperitoneal abscesses.

Bacteriology

The flora in the normal appendix is similar to that in the colon, with various facultative aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. The polymicrobial nature of perforated appendicitis is well established. Escherichia coli, Streptococcus viridans, and Bacteroides and Pseudomonas spp. are frequently isolated, and many other organisms may be cultured (Table 51-1). Among patients with an acute nonperforated appendicitis, cultures of peritoneal fluid are frequently negative and are of limited use. Among patients with perforated appendicitis, peritoneal fluid cultures are more likely to be positive, revealing colonic bacteria with predictable sensitivities. Because it is rare that the findings alter the selection or duration of antibiotic use, some have challenged the traditional practice of obtaining cultures.5

Table 51-1 Bacteria Commonly Isolated in Perforated Appendicitis

| TYPE OF BACTERIA | PATIENTS (%) |

|---|---|

| Anaerobic | |

| Bacteroides fragilis | 80 |

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | 61 |

| Bilophila wadsworthia | 55 |

| Peptostreptococcus spp. | 46 |

| Aerobic | |

| Escherichia coli | 77 |

| Streptococcus viridans | 43 |

| Group D streptococcus | 27 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 18 |

Adapted from Bennion RS, Thompson JE: Appendicitis. In Fry DE (ed): Surgical infections, Boston, 1995, Little, Brown, pp 241–250.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of appendicitis can include almost all causes of abdominal pain, as described in the classic treatise, Cope’s Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen.6 A useful rule is never to place appendicitis lower than second in the differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in a previously healthy person.

History

Appendicitis needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of almost every patient with acute abdominal pain. Early diagnosis remains the most important clinical goal in patients with suspected appendicitis and can be made primarily on the basis of the history and physical examination in most cases. The typical presentation begins with periumbilical pain, caused by the activation of visceral afferent neurons, followed by anorexia and nausea. The pain then localizes to the right lower quadrant as the inflammatory process progresses to involve the parietal peritoneum overlying the appendix. This classic pattern of migratory pain is the most reliable symptom of acute appendicitis.7 A bout of vomiting may occur, in contrast to the repeated bouts of vomiting that typically accompany viral gastroenteritis or small bowel obstruction. Fever ensues, followed by the development of leukocytosis. These clinical features may vary. For example, not all patients become anorexic. Consequently, the feeling of hunger in an adult patient with suspected appendicitis should not necessarily be a deterrent to surgical intervention. Occasional patients have urinary symptoms or microscopic hematuria, perhaps because of inflammation of periappendiceal tissues adjacent to the ureter or bladder, and this may be misleading. Although most patients with appendicitis develop an adynamic ileus and absent bowel movements on the day of presentation, occasional patients may have diarrhea. Others may present with small bowel obstruction related to contiguous regional inflammation. Therefore, appendicitis needs to be considered as a possible cause of small bowel obstruction, especially in patients without prior abdominal surgery.

Radiographic Studies

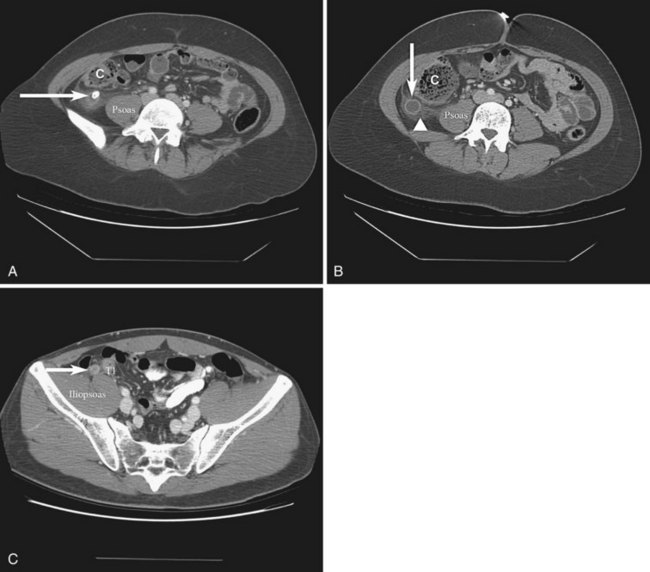

Computed tomography (CT) is commonly used in the evaluation of adult patients with suspected acute appendicitis. Improved imaging techniques, including the use of 5-mm sections, have resulted in increased accuracy of CT scanning,8 which has a sensitivity of approximately 90% and a specificity of 80% to 90% for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in patients with abdominal pain. Results of a recent randomized study have suggested that the use of high-resolution multidetector CT (64-MDCT) with or without oral or rectal contrast results in more than 95% accuracy in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis.9 In general, CT findings of appendicitis increase with the severity of the disease. Classic findings include a distended appendix more than 7 mm in diameter and circumferential wall thickening and enhancement, which may give the appearance of a halo or target (Fig. 51-1). As inflammation progresses, one may see periappendiceal fat stranding, edema, peritoneal fluid, phlegmon, or a periappendiceal abscess. CT detects appendicoliths in approximately 50% of patients with appendicitis and also in a small percentage of people without appendicitis. In patients with abdominal pain, the positive predictive value of the finding of an appendicolith on CT remains high (≈75%).

Should CT be used routinely in the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected appendicitis? We do not recommend it, but one study has found that liberal use of CT scans is probably warranted because this has been credited with a declining incidence of negative appendectomy (i.e., the fraction of pathologically normal appendices that are removed).10 In the setting of typical right lower quadrant pain and tenderness with signs of inflammation in a young male patient, a CT scan is unnecessary, wastes valuable time, may be misinterpreted, and exposes the patient to risks for allergic contrast reaction, nephropathy, aspiration pneumonitis, and ionizing radiation. The latter carries increased risk in children in whom the rate of radiation-induced cancer has been estimated at 0.18% following an abdominal CT scan.11 CT has proved most valuable for older patients in whom the differential diagnosis is lengthy, clinical findings may be confusing, and appendectomy carries increased risk.12,13 In patients with atypical symptoms, CT scan may reduce the negative appendectomy rate. Liberal use of cross-sectional imaging seems most appropriate and, as always, the study needs to be performed only in settings in which it has a significant potential to alter management. Given the recent increased awareness of the risks of cumulative radiation exposure in young adults undergoing CT scanning,14 it remains to be seen whether magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will replace CT as the preferred modality for the evaluation of the appendix in younger patients.

The morbidity rate of perforated appendicitis far exceeds that of a negative appendectomy. Thus, the strategy has been to set a low enough threshold for removal of the appendix to minimize the cases of missed appendicitis. With increased use of CT, the frequency of negative explorations has declined in recent years, without an accompanying rise in the number of perforations. An analysis of more than 75,000 patients from 1999 to 2000 revealed a negative appendectomy rate of 6% in men and 13.4% in women.12

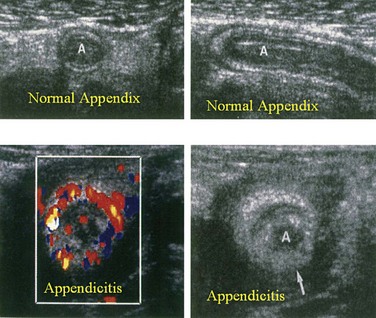

Among patients with abdominal pain, ultrasonography has a sensitivity of approximately 85% and a specificity of more than 90% for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Sonographic findings consistent with acute appendicitis include an appendix of 7 mm or more in anteroposterior diameter, a thick-walled, noncompressible luminal structure seen in cross section, referred to as a target lesion, or the presence of an appendicolith (Fig. 51-2). In more advanced cases, periappendiceal fluid or a mass may be found. Ultrasonography has the advantages of being a noninvasive modality requiring no patient preparation that also avoids exposure to ionizing radiation. Thus, it is commonly used in children and in pregnant patients with equivocal clinical findings suggestive of acute appendicitis. Ultrasonography has been shown to change the disposition of 59% of children with abdominal pain who had already been evaluated by the surgical team.15 Disadvantages of ultrasonography include operator-dependent accuracy and difficulty interpreting the images by those other than the operator. Because performance of the study may require hands-on participation by the radiologist, ultrasonography may not be readily available at night or on weekends. Pelvic ultrasound can be especially useful in excluding pelvic pathology, such as tubo-ovarian abscess or ovarian torsion, which may mimic acute appendicitis.

Although they are commonly obtained, the indiscriminate use of plain abdominal radiographs in the evaluation of patients with acute abdominal pain is unwarranted. In one study of 104 patients with acute onset of right lower quadrant pain, interpretation of plain x-rays changed the management of only six patients (6%) and, in one case, contributed to an unnecessary laparotomy.16 A calcified appendicolith is visible on plain films in only 10% to 15% of patients with acute appendicitis. Although its presence strongly supports the diagnosis in a patient with abdominal pain, the low sensitivity of this test renders it of little value in preoperative decision making. Plain abdominal films may be useful for the detection of ureteral calculi, small bowel obstruction, or perforated ulcer, but such conditions are rarely confused with appendicitis. Failure of the appendix to fill during a barium enema has been associated with appendicitis, but this finding lacks sensitivity and specificity because up to 20% of normal appendices do not fill.

Special Patient Populations

The diagnosis of appendicitis is particularly difficult in the very young and in older adults. It is in these groups that diagnosis is most often delayed and perforation occurs most frequently. Imaging studies are strongly considered here. Because of increasing concerns about radiation-induced cancers in children,11 ultrasonography is the preferred initial imaging modality for this group. For older patients, CT offers the ability to detect the broader array of conditions, such as diverticulitis and malignancy, found in the differential diagnosis.

In school-aged children, gastroenteritis often presents with abdominal pain and diarrhea, without fever or leukocytosis. The most common condition that mimics appendicitis in this population is mesenteric lymphadenitis, which may be caused by a wide variety of enteric infections.17 Ultrasonography may be helpful for identifying enlarged lymph nodes in the region of the ileal mesentery in conjunction with thickening of the ileal wall and a normal appendix, in which case appendectomy may be avoided. MRI may be helpful to resolve ambiguous sonographic or clinical findings. It is important to remember that enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes may also be the result of acute appendicitis. Inflammatory bowel disease is also considered in children, particularly if there is a history of recurrent episodes of abdominal pain. Constipation and functional pain are common in this age group. Although constipation may be associated with relatively severe pain, there are no peritoneal signs, fever, or leukocytosis, and the diagnosis is supported by a recent history of hard stools. Functional pain is usually somewhat milder, recurrent, and self-limited.

Appendicitis is the most common nonobstetric surgical disease of the abdomen during pregnancy. Diagnosis may be difficult because symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and anorexia, as well as elevated white blood cell count, are common during pregnancy. Moreover, the location of tenderness varies with gestation. After the fifth month of gestation, the appendix is shifted superiorly above the iliac crest and the appendiceal tip is rotated medially into the right upper quadrant by the gravid uterus. Ultrasound is helpful for establishing the diagnosis and location of the inflamed appendix. In cases in which ultrasound has been equivocal, MRI has been used successfully, thereby avoiding ionizing radiation exposure to the developing fetus. The main challenge is to recognize the possibility of appendicitis in pregnant patients and intervene promptly, because peritonitis significantly increases the rate of fetal loss (2.6% to 10.9% in one meta-analysis).18 The challenge in the diagnosis is to balance this risk of perforation and risk of fetal demise and preterm labor from delayed diagnosis against the risk of a negative appendectomy. Laparoscopic appendectomy has been performed through the second trimester of pregnancy, although data are lacking comparing this approach to the open procedure.

Appendicitis in older patients can be difficult to diagnose because many patients delay seeking care and the presentation may be atypical. Fever is uncommon, the white blood cell count may be normal, and many older patients with appendicitis do not experience right lower quadrant pain. Approximately 50% of older patients are incorrectly diagnosed at the time of admission and they have a much higher rate of perforation at the time of surgery because of delays in operative intervention.13 More than 50% of older patients with appendicitis are found to have perforated appendices, compared with fewer than 20% of younger patients. Diverticulitis and bowel obstruction are common misdiagnoses in older patients; the differential diagnosis also includes malignancies of the gastrointestinal tract and reproductive system, perforated ulcers, and cholecystitis. CT has become an invaluable tool for the evaluation of abdominal pain in older patients and its use has shortened preoperative hospital delays.13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree