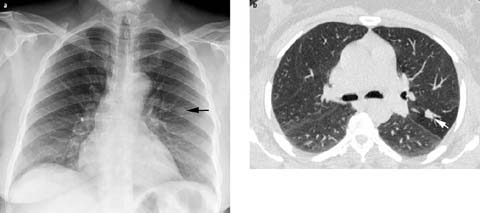

Fig 1 a, b.

Left upper lobe atelectasis. Postera-anterior (PA) chest radiograph (a) shows left upper lobe atelectasis manifesting as a vague left upper lung zone opacity with elevation of the left hemidiaphragm. The lateral chest radiograph (b) shows the opaque atelectatic left upper lobe and anterosuperior displacement of the major fissure (arrows). The etiology of the atelectasis was a left upper lobe lung cancer

Direct signs of atelectasis include fissurai displacement, bronchovascular crowding, and shift of calcified granulomas. Indirect signs include increased pulmonary opacity, ipsilateral mediastinal shift, hilar displacement, ipsilateral hemidiaphragm elevation, and compensatory hyperinflation of the adjacent lung [2].

Parenchymal Opacities

Parenchymal opacities include alveolar and interstitial processes. Pneumonia typically manifests with consolidation due to alveolar filling by purulent material and may be lobar or sublobar, or it may manifest with patchy pulmonary opacities. Consolidation often exhibits intrinsic air bronchograms and may also result from alveolar edema or hemorrhage (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of air space opacification (ASO)

Finding(s) | Disease |

|---|---|

Focal/segmental ASO | Pneumonia, contusion, infarct, lung cancer (adenocarcinoma) |

Lobar ASO | Pneumonia, endogenous lipoid pneumonia, adenocarcinoma |

Patchy ASO | Infection, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, adenocarcinoma, metastases, emboli |

Diffuse ASO | Edema, hemorrhage, pneumonia |

Perihilar ASO | Edema, hemorrhage |

Peripheral ASO | Eosinophilic pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, contusion |

Rapidly changing/resolving ASO | Edema, eosinophilic pneumonia, hemorrhage |

A pulmonary nodule is defined as a round or ovoid density <3 cm in diameter [3]. A benign pattern of intrinsic calcification allows the confident diagnosis of granuloma, for which further evaluation is not required. However, many pulmonary nodules are indeterminate on radiography and require further assessment and characterization with computed tomography (CT) to exclude malignancy (Fig. 2 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis of the solitary pulmonary nodule

Finding(s) | Disease |

|---|---|

Granuloma | |

Primary malignancy: Lung cancer, carcinoid tumor | |

Solitary metastasis | |

Hamartoma | |

Focal organizing pneumonia | |

Hematoma |

Fig 2 a, b.

Solitary pulmonary nodule. a PA chest radiograph shows a nodule in the left mid lung zone (arrow), b Unenhanced chest computed tomography (CT) (lung window) shows a lobular soft-tissue nodule (arrow) in the left upper lobe. Typical carcinoid tumor was diagnosed by CT-guided needle biopsy

A pulmonary mass is a round or ovoid pulmonary opacity ⩾3 cm in diameter and is highly suspicious for malignancy, typically lung cancer. The radiologist should look for pertinent ancillary findings of malignancy including other lung nodules, lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion, and chest wall involvement.

Interstitial opacities may manifest with reticular, linear, and/or small nodular opacities. As the normal interstitium is not visible on radiography, visualization of peripheral subpleural reticular opacities is always abnormal. A reticulonodular pattern occurs when abnormal linear opacities are superimposed on micronodular opacities. Interstitial opacities frequently result from interstitial edema characterized by perihilar haze, peribronchial thickening, septal thickening, and subpleural edema often associated with cardiomegaly and pleural effusion [4]. Associated radiographic findings can help limit the differential diagnosis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Ancillary findings in patients with interstitial lung disease and differential diagnostic considerations

Finding(s) | Disease |

|---|---|

Hilar lymph node enlargement | Sarcoidosis, lymphangitic carcinomatosis, viral pneumonia |

Clavicular/osseous erosions | Rheumatoid associated ILD (UIP, NSIP) |

Pleural effusion | Infection, edema |

Pleural plaques | Asbestosis |

Hyperinflation | PLCH, end-stage sarcoidosis, lymphangio leiomyomatosis, emphysema with UIP |

Esophageal dilatation | Scleroderma associated ILD (UIP, NSIP), recurrent aspiration |

Conglomerate masses | Silicosis, sarcoidosis, talcosis |

Basilar sparing | PLCH, sarcoidosis |

Basilar predominance | UIP, aspiration |

Cells and fibrosis may also infiltrate the pulmonary interstitium, producing reticular and reticulonodular interstitial opacities in diseases such as sarcoidosis, siliciosis, and lymphangitic carcinomatosis.

The idiopathic interstitial pneumonias are a distinct group of disorders often characterized by basilar predominant pulmonary fibrosis associated with volume loss. The diagnosis usually requires further imaging with high-resolution chest CT to assess for the presence or absence of honeycombing (Fig. 3).

Fig 3 a, b.

Interstitial lung disease. a PA chest radiograph of a 62-year-old man with chronic progressive dyspnea shows diffuse bilateral peripheral reticular interstitial opacities and low lung volumes. b Coronal contrast-enhanced chest CT shows subpleural reticulation, traction bronchiectasis (arrow), and honeycomb cysts (arrowhead), consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia

Airways

The trachea and bronchi should be assessed for size, patency, and course. Tracheal narrowing may be focal or diffuse. Focal tracheal narrowing or stenosis often results from mucosal damage from prolonged intubation. Airway neoplasms may manifest as endoluminal soft-tissue nodules that may be associated with volume loss. Endotracheal tumors may grow to obstruct up to 75% of the airway lumen before symptoms ensue. Airway neoplasms may also manifest as focal or diffuse airway stenosis and must be differentiated from inflammatory processes that may produce airway stenosis. Bronchiectasis is defined as irreversible bronchial dilatation and may result from infection, cystic fibrosis, primary ciliary dyskinesia, or allergic bronchopulmonary fungal disease [5].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree