Figure 2.1

Age in years

One of the most interested yet challenging features regarding the management of syncope is the diverse range of significance of a syncopal episode. Syncope can be a very benign, explicable almost anticipated outcome of a predictable setting. On the other hand, syncope may the one and only presenting symptom of a life threatening disease. Given the staggeringly broad causes and consequences of a syncopal episode, the treating physician has two goals.

1.

Identify the cause of the syncope in order to guide treatment based on the underlying etiology

2.

Identify the specific risk to the patient. This includes not only the risk of recurrent syncope, but also the risks associated with the underlying [16].

For the physician managing syncope, risk stratification, which is based on the etiology of the syncopal episode, becomes perhaps the most important role.

Syncope is derived from the Greek word synkopē, which means “to cut short” or “to interrupt”. Syncope is defined by transient loss of consciousness due to global cerebral hypoperfusion. Syncope is characterized by rapid onset, short duration, and spontaneous complete recovery.

There are many syndromes that may present as masquerading syncope. These include falls, cataplexy, TIAs, seizures, psychogenic pseudosyncope, metabolic disorders, intoxication, and vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Because of confusion in the etiology of these episodes, many of these patients are referred to the electrophysiologist for the evaluation of the cardiac conduction system. It is important to discern the features that suggest a non-syncopal alternation in consciousness. A thorough history should differentiate these other forms of altered consciousness from the sudden loss of consciousness due to a global, reversible reduction in blood flow (Fig. 2.2).

Figure 2.2

Syncope Defined

Testing done in the electrophysiology lab is performed to evaluate whether syncope resulted from bradycardia, tachycardia, or a reproducible cardiac reflex or autonomic abnormality. Prior to undergoing testing, a thorough history is essential to help correctly classify syncope. The 2009 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of syncope provide an excellent framework for the classification of syncope based on etiology [3] (Fig. 2.3).

Figure 2.3

Relative incidence of syncope by pathophysiological classification

Insufficient cerebral perfusion is the hallmark of syncope. The insults that result in an abrupt reduction of cerebral blood flow are many and varied. A fall in systemic blood pressure curtails global cerebral blood flow. If blood flow is significant diminished for as short as for 6–8 s, syncope may ensue. Systemic blood pressure is determined by systemic vascular resistance and cardiac output. Cardiac output is the product of heart rate and stroke volume. Syncope may result from a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance, a reduction in heart rate, a reduction in stroke volume, or a reduction in a combination of mechanisms [16] (Fig. 2.4).

Figure 2.4

Pathophysiologic Basis of the Classification of Syncope

Reflex Syncope

Reflex syncope, also correctly termed neutrally mediated syncope, accounts for more than half of syncope. Determining the mechanism of the reflex syncope episodes is paramount for effective treatment and prevention. Reflex syncope should be thought of as a spectrum of inappropriate reflexes. Vasodepressor syncope, characterized by a profound hypotensive response is at one end of the spectrum and cardioinhibitory syncope, characterized by asystolic pauses, is at the other end of the spectrum. While the etiology is the same, the hemodynamic responses may be markedly different. Identifying where on this spectrum the patient lies, guides the treating physician to effective therapy. No longer is it appropriate to apply across the board treatment to the spectrum of neutrally mediated syncope. For patients in whom a vasodepressor response is the overriding perturbation, volume expansion, vasoconstriction and blood pressure augmentation is the mainstay of treatment. Patients that have a primary cardioinhibitory response to reflex-provoking stimuli may benefit from pacemaker therapy. This has been demonstrated in the Eastbourne Syncope Assessment Study, where implantable loop recorders effectively guided syncope therapy [6].

The most common etiology of syncope is a neutrally mediated reflex triggered by different stimuli leading to sudden withdrawal of sympathetic activity and to an increase in parasympathetic nerve tone. The results are vasodilatation and bradycardia. Neurally mediated syncope is classically precipitated extrinsic factors, be it physical or emotional triggers. This includes prolonged standing leading to venous pooling as well as emotional triggers such as fear, needle phobia, pain, and stage fright (Fig. 2.5).

Figure 2.5

Vasovagal Reflex Syncope

Another form of neutrally mediated syncope is situational syncope. There are specific triggers that elicit abnormal hemodynamic responses leading to the symptomatic global hypoperfusion (Fig. 2.6).

Figure 2.6

Situational Reflex Syncope

Carotid sinus hypersensitivity is another form of reflex syncope. While other forms of reflex syncope may occurs throughout all stages of life, this typically presents >50 years of age. It is more common in men than in women. An abnormal response to carotid sinus massage is defined as a pause for more than three seconds or a drop in systolic blood pressure greater than 50 mmHg. Normally a mixed picture of vasodepressor and cardioinhibitory response is elicited (Fig. 2.7).

Figure 2.7

Carotid Sinus Hypersensitiity Reflex Syncope

Syncope Due to Orthostatic Hypotension

An abnormal vasoconstriction response to upright position can results in decreased cerebral perfusion. When upright, 10–15 % of blood pools in the lower extremities. The baroreceptors are activated by the decreased pressure that results from this drop in venous return and drop in stroke volume. A normal response increased heart rate, increased contractility and restored vascular tone. However, an abnormal response to these triggers may result in orthostatic intolerance if normal stroke volume is not restored. An abnormal response to upright posture is defined as a decrease in systolic blood pressure >20 mmHg or a decrease of symptomatic fall of systolic blood pressure associated with syncope or pre-syncope (Fig. 2.8).

Figure 2.8

Orthostatic Hypotension Syncope

Cardiac Syncope

Cardiac syncope requires the most accurate diagnosis, as it may be the first sign of a life-threatening disorder. The absence of a prodrome is a common feature of these high-risk syncope scenarios. As a result, the risk of trauma is much higher with cardiac syncope. Exertional syncope should initiate a search for a cardiac cause of syncope (Figs. 2.9 and 2.10).

Figure 2.9

Cardiac Syncope

Figure 2.10

Obstruction to cardiac output is another cause of syncope. While this type of cardiac syncope is less common, it carries with it a high mortality [17].

Arrhythmias also impede cardiac output. The sudden change in heart rate, wither fast or slow, may drastically reduce the cardiac output. In some patients with SVT, the cardiac output is still sufficient to maintain cerebral perfusion, but a mixed picture with a vasodepressor response occurs, resulting in syncope [12].

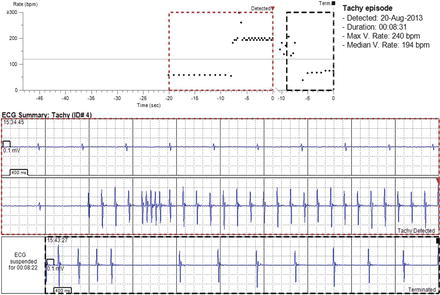

In patient with a suspicion for arrhythmogenic syncope, but yet undocumented rhythm disturbances, lengthy monitoring is often required. The implantable loop recorder has proven to be very useful in this regard. The ILR provides a cost-efficient and timely method to correlate heart rhythm at the time of syncope or presyncopal symptoms. This leads to the appropriate intervention, be it pacemaker, defibrillator, electrophysiology study with ablation, or medical therapy. Even documenting normal sinus rhythm at the time of symptoms can efficiently reroute the management in the effective direction (Fig. 2.11).

Tilt Table Testing

Tilt table testing is utilized to help investigate the underlying cause of unexplained syncope. Tilt table testing was first used to diagnose syncope in 1986 [10]. The test helps demonstrate the hemodynamic response to a passive upright challenge. It can help define the mechanism with neutrally mediated syncope or orthostatic hypotension syncope is suspected. If the detailed clinical history, along with a normal exam, normal echo, and normal ECG all suggest neutrally mediated syncope, a tilt table test may not be necessary to solidify the diagnosis [5]. However, there are times when a formal test is useful. Fortunately, tilt table testing is easy, safe, well tolerated, and often contributes to the patients understanding of their clinical situation. It also plays a role in defining dysautonomia syndromes, such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome and orthostatic intolerance.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree