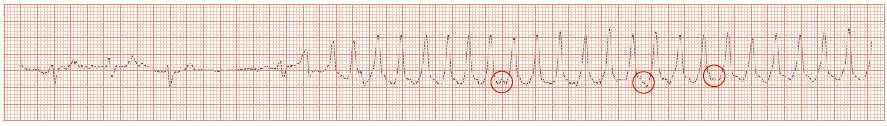

Fig. 23.2 Rhythm strip from monitoring in recent syncope. The heart slows, then a run of ventricular tachycardia (VT) starts (fast broad complex tachycardia, showing independent P wave activity). Syncopal VT due to structural heart disease.

Syncope is ‘loss of consciousness with loss of postural reflexes’. The key to diagnosis is to record an ECG (and preferably blood pressure) before and during a spontaneous attack. This is often quite a difficult thing too, although sometimes ambient monitoring allows this. Equally, on occasions, it is sometimes possible to induce an attack to obtain this data. Good clues to the diagnosis can be obtained from the history, physical exam and ECG alone (Table 23.1):

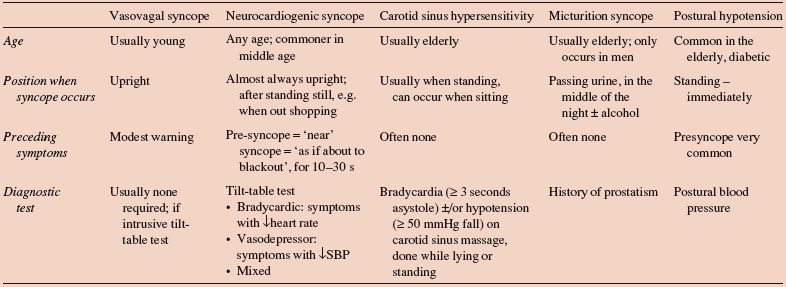

‘Vasomotor’ syncope relates to altered circulatory control lowering blood pressure (Table 23.2). The clues to this diagnosis are: (i) warning before an attack; (ii) gradual collapse (i.e. some protective reflexes remain intact); (iii) brief loss of consciousness; (iv) injury is very rare; (v) syncope may be situation specific, e.g. only occur in church, etc.

Bradyarrhythmias usually pauses of ≥ 4 s are required to cause syncope, e.g. sinus node disease, heart block. The clues to the diagnosis include: (i) older age patient, often > 70 years; (ii) no warning; (iii) injury as a consequence of the event is comon.

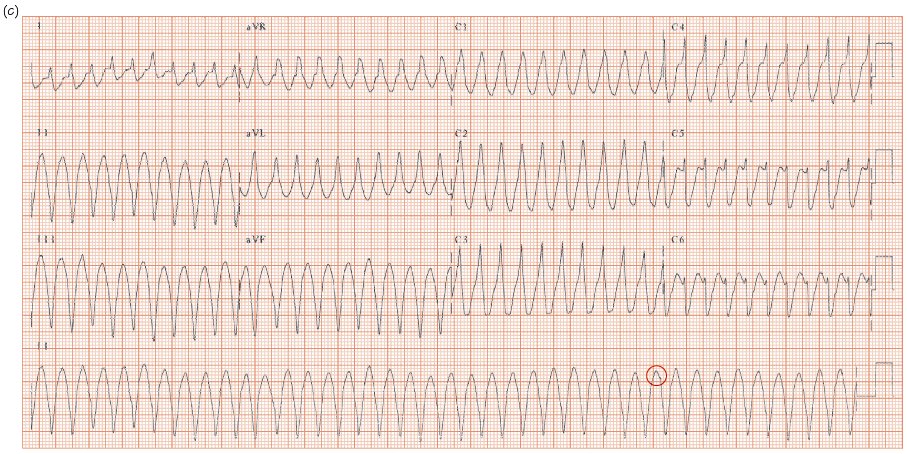

Tachyarrhythmias need to be fast to cause syncope ≥ 250–300 b/min; e.g. atrial fibrillation (AF) with Wolff–Parkinson–White (WPW) syndrome, associated with structural heart disease (e.g. ventricular tachycardia [VT] with moderate left ventricular [LV] dysfunction, AF with severe LV dysfunction), or ventricular and completely disorganized (torsade-de-pointes). The clues to the diagnosis include: (i) palpitations often (not always) felt before the syncope; (ii) injury common; (iii) most patients (not all) either are known to have structural heart disease (e.g. previous myocardial infarction), or have an abnormal inter-attack ECG.

Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction effort-induced syncope occurs in severe aortic stenosis, diagnosed from the physical exam and ECG (LV hypertrophy). Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy causes similar symptoms, with a bizarre ECG. Cardiac ultrasound defines either condition. The clues to the diagnosis are that symptoms of near or actual syncope occur on effort (see below).

Pulmonary hypertension needs to be severe (≥ 80–100 mmHg) to cause effort-induced syncope. The ECG may show right ventricular hypertrophy.

Epilepsy is usually so obvious that there is no doubt as to the diagnosis. Occasionally undiagnosed arrhythmias underlie seizures e.g. hereditary long QT syndrome.

Situations mimicking syncope include hyperventilation and psychogenic causes.

Table 23.1 Inter-attack ECG in syncope.

| Interpretation | Further management | |

| Normal | Arrhythmia unlikely, not excluded | If vasomotor syncope likely – tilt-table test; if unlikely, and injury present – Reveal® device |

| RBBB | Non-specific | Exclude Brugada syndrome (consider ajmaline flecainide challenge) |

| Long PR interval | Heart block possible; other causes should still be considered | If history of Stokes–Adams attack, permanent pacemaker; if CAD, consider EP study to: (i) measure AH, HV intervals; (ii) to exclude inducible VT; otherwise Reveal® device |

| Trifasicular block* | Heart block likely | Pacemaker |

| Q waves | VT related to the scar of the old MI | Ventricular stimulation study or Reveal® device |

| LVH | Aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. If hypertensive, VT may underlie syncope | Cardiac ultrasound AVR for aortic stenosis; specialist management for HCM; otherwise Reveal device® |

| Long QT interval | Polymorphic VT | (i) Exclude relevant drugs; (ii) beta-blockers; (iii) ICD; (iv) family screening |

*, Long PR interval + RBBB and L or R axis deviation.

AH, atrial – His conduction time; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CAD, coronary artery disease; EP, electrophysiology; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HV, His – ventricular conduction time; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MI, myocardial infarction; RBBB, right bundle branch block; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Table 23.2 Vasomotor syncope.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree