Syncope

Syncope will occur in up to 50% of the population and is defined by the abrupt loss of consciousness due to cerebral hypoperfusion. Syncope must be distinguished from seizures, in which case loss of consciousness occurs without cerebral hypoperfusion, falls, drop attacks without loss of consciousness, falling asleep, and psychogenic episodes. In the vast majority of instances there is insufficient monitoring (blood pressure, pulse) at the time of the clinical event to clearly identify the cause. It is therefore necessary to rely heavily on the description of the event from the patient and witnesses as well as the medical history of the patient and first-degree family members. Close attention to these factors will help guide a focused clinical evaluation.

Differential Diagnosis

Reflex Syncope

Neurally mediated or reflex syncope accounts for >50% of syncope diagnoses (see Table 12-1). This category of diseases includes neurocardiogenic syncope (a term which encompasses vasovagal and vasodepressor syncope); carotid sinus hypersensitivity; and situational causes such as syncope associated with prolonged standing, micturition, defecation, or coughing. Vasovagal syncope can occur at any age. It may or may not be associated with a prodrome of

nausea and/or vomiting. The mechanism is believed to be related to autonomic activation. In most instances, a decrease in venous filling such as occurs with peripheral venous pooling results in a compensatory sympathetic activation to maintain blood pressure. This activates peripheral baroreceptors, most notably those in the aorta and occasionally C fibers in the inferoposterior aspect of the left ventricle (LV) (also activated with inferior myocardial ischemia as part of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex). There is a resultant central and eventual peripheral withdrawal of sympathetic tone and increase in parasympathetic tone. This may manifest in a number of ways including the following:

nausea and/or vomiting. The mechanism is believed to be related to autonomic activation. In most instances, a decrease in venous filling such as occurs with peripheral venous pooling results in a compensatory sympathetic activation to maintain blood pressure. This activates peripheral baroreceptors, most notably those in the aorta and occasionally C fibers in the inferoposterior aspect of the left ventricle (LV) (also activated with inferior myocardial ischemia as part of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex). There is a resultant central and eventual peripheral withdrawal of sympathetic tone and increase in parasympathetic tone. This may manifest in a number of ways including the following:

Bradycardia with sinus arrest and/or varying degrees of atrioventricular (AV) nodal block resulting in hypotension (cardioinhibitory response)

Marked vasodilation with a normal or slightly increased sinus rate (vasodepressor response)

Mixture of vasodilation and bradycardia

TABLE 12-1 General Categories of Syncope

| Reflex Syncope | Obstructive Causes | Arrhythmias | Orthostasis | Seizures |

| HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HTN, hypertension. | ||||

| Neurocardiogenic | Aortic stenosis | Bradycardia | Blood loss | Grand mal |

| Carotid sinus hypersensitivity | HCM | Tachycardia | Autonomic insufficiency | — |

| Pulmonary embolus | — | — | — | |

| Situational | Pulmonary HTN | — | Drug-induced | — |

| Atrial myxoma | — | Adrenal insufficiency | — | |

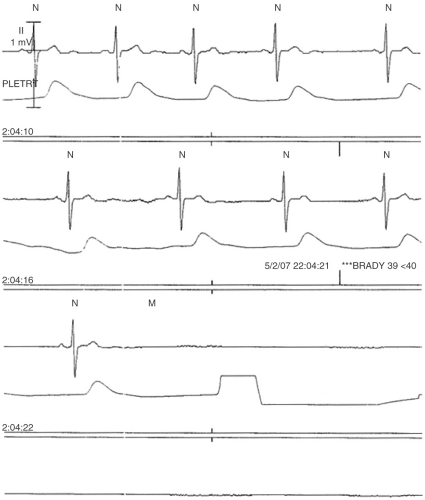

When bradycardia is noted, there is often gradual slowing of the sinus rate with or without AV block or a ventricular escape rhythm (see Fig. 12-1).

This disorder can develop at any age and may be associated with multiple affected family members. It is not unusual for recurrent episodes of neurally mediated syncope to occur over decades of life. Patients may experience these episodes in clusters. Attempts at preventing neurocardiogenic syncope are generally unsuccessful. Fortunately, this form of syncope rarely occurs in circumstances which could pose a high risk for damage such as driving a car. One exception is syncope in the bathroom where hard surfaces can inflict significant injury.

Carotid sinus hypersensitivity occurs through activation of an overly sensitive carotid body and is associated with prolonged periods of asystole and secondary hypotension. This disorder is rarely seen before the age of 40 and occurs most often in those older than 60 years of age.

Obstructive: Cardiopulmonary

Syncope can occur due to a drop in cardiac output in the setting of fixed or dynamic cardiovascular or pulmonary obstruction. Syncope can occur with

critical aortic stenosis when vasodilation occurs and cardiac output cannot be sufficiently augmented. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy can cause syncope particularly when associated with an acute drop in preload such as standing up quickly, often in the setting of dehydration. Rarely, intermittent obstruction of the mitral valve with a mobile mass such as a myxoma can result in syncope. Severe fixed pulmonary hypertension or pulmonary obstruction associated with a large pulmonary embolus can also result in syncope due to reduced LV filling and cardiac output.

critical aortic stenosis when vasodilation occurs and cardiac output cannot be sufficiently augmented. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy can cause syncope particularly when associated with an acute drop in preload such as standing up quickly, often in the setting of dehydration. Rarely, intermittent obstruction of the mitral valve with a mobile mass such as a myxoma can result in syncope. Severe fixed pulmonary hypertension or pulmonary obstruction associated with a large pulmonary embolus can also result in syncope due to reduced LV filling and cardiac output.

Arrhythmic

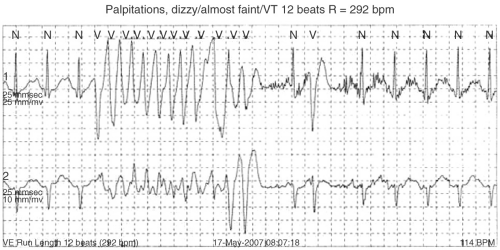

Ventricular and less commonly supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) can cause syncope. Syncope in association with ventricular tachycardia (VT) is generally related to diminished output in a poorly functioning ventricle. Syncope due to VT can be the initial manifestation of acute myocardial infarction. Nonsustained polymorphic VT associated with acquired or congenital long QT syndrome is also an important cause of syncope. Children with unrecognized long QT syndrome may carry a history of syncope or seizure disorder until the QT interval is recognized to be abnormal. Non sustained polymorphic VT or VF can also be seen in patients without structural heart disease and can present with syncope or sudden death (see Fig. 12-2). Syncope in association with SVT (e.g., atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia [AVNRT]) is very unusual but when it occurs it is felt likely due to a baroreceptor response and generally occurs immediately after the onset of SVT. Syncope in association with atrial fibrillation (AF) is a special circumstance. AF with preexcitation can result in syncope or sudden death due to the induction of ventricular arrhythmia. More commonly, AF is associated with syncope due to a pause at the time of conversion of AF to sinus rhythm (see Fig. 6-3). Atrial flutter associated with

sodium channel blocking drugs such as flecainide or propafenone can produce a wide QRS complex and impaired myocardial contraction which can result in syncope.

sodium channel blocking drugs such as flecainide or propafenone can produce a wide QRS complex and impaired myocardial contraction which can result in syncope.

Bradyarrhythmias can cause syncope due to sinus pauses or AV block. In general sinus pauses are >3 to 5 seconds when associated with syncope. AV block can occur in the AV node or below and if an escape rhythm is absent can result in syncope. A cause of high-grade AV block in the absence of apparent preexisting conduction disease is paroxysmal AV block. This disorder is characterized by the abrupt development of AV block with slight changes in the sinus rate or following a premature atrial or ventricular beat (see Chapter 11). It is a sporadic and unpredictable event.

Bradyarrhythmias, particularly complete heart block, can also result in QT prolongation and torsade de pointes.

Neuropsychiatric

The major neurologic causes of syncope include seizure disorder and autonomic insufficiency (discussed in subsequent text). Seizure disorder is an important cause of loss of consciousness, which must be distinguished from myoclonus which can occur with all forms of true syncope. It is important to stress that strokes and transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) do not cause syncope unless there is global cerebral hypoperfusion or a seizure as a consequence of a prior stroke. Vertebrobasilar insufficiency causes “drop attacks” which are manifested as a fall due to unsteadiness or feeling as though ones “legs gave out” without a loss of consciousness.

Psychogenic or pseudosyncope are witnessed or reported episodes of feigned syncope. Patients with this disorder frequently have a psychiatric history.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree