Symptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis

MOHAMMAD H. ESLAMI and ZACHARIAH K. ESLAMI

Presentation

A 65-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with right-sided paralysis and expressive aphasia. Her husband told the emergency room physician that the patient has a history of hypertension, smoking, and myocardial infarction that was treated with coronary artery angioplasty and stenting. Her husband recalls that she had an episode of slurred speech and difficulty seeing from her left eye while visiting relatives in Ireland 3 weeks ago. This quickly resolved, and she did not seek medical attention. On physical examination, she is in normal sinus rhythm and has a loud left-sided carotid bruit. Neurologically, initially, she has decreased strength (2/5) on the right side that has gradually improved to almost normal. Her facial drooping and expressive aphasia have resolved, and she is now able to communicate.

Differential Diagnosis

The most common cause of transient cerebral ischemia is embolization from atherosclerotic disease of the extracranial carotid artery and specifically from stenotic internal carotid artery (ICA). Embolization can also originate from cardiac sources (atrial thrombus, valvular vegetative disease, atrial fibrillation), fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), stenosis of the carotid artery, carotid dissection, carotid kink or coils, aneurysms of extracranial carotid arteries, or paroxysmal arterial emboli. Neurologic symptoms may also be caused by migraine headaches and even giant cell arteritis. Considering this patient’s age and cardiovascular risk factors (h/o of MI, hypertension, and tobacco abuse) and the presence of loud carotid bruit, ICA stenosis should be considered the primary source of cerebral ischemia.

Discussion

Carotid artery stenosis can cause neurologic symptoms ranging from transient cerebral ischemia to dense permanent cerebral stroke. Transient cerebral ischemia is self-limiting with neurologic deficit that lasts for less than 24 hours that completely resolves. The term encompasses different presentations, such as transient monocular blindness (TMB), also known as amaurosis fugax and lateralizing transient ischemic attacks (TIA). TMB is classically described as having a “curtain over the eye” or “a shade pulled over the eye” that clears in seconds to a few minutes. Lateralizing TIAs commonly manifest as weakness or paresthesia that affect the contralateral body. By definition, the duration of a TIA is less than 24 hours; however, they frequently last only several minutes to an hour before resolving without a residual neurologic deficit. Physicians rarely see patients during transient attacks, and the patient’s history remains the primary factor in establishing a diagnosis.

In the spectrum of presentation of carotid artery stenosis from transient to complete cerebral ischemia (stroke), there are two conditions known as crescendo TIA or stroke in evolution that need special attention. Crescendo TIA describes the situation when a patient experiences frequent repetitive neurologic attacks without complete resolution of the deficit between the episodes, producing the same deficit but no progressive deterioration in neurologic function. If a progressive deterioration in neurologic function is seen, the patient is diagnosed as experiencing a stroke in evolution. If there is a surgically correctable lesion that is identified as the primary source of cerebral embolization, these two conditions are the only time that an emergent operation is indicated.

Flow-related ischemic events are unusual due to an extremely efficient collateral blood supply to the brain, primarily through the circle of Willis. When they do occur, flow-related ischemic events are usually associated with carotid dissections often after a hypertensive crisis or traumatic injury to the carotid artery. Most commonly, cerebral ischemic attacks are caused by thromboembolic events from an arterial nidus. The arterial nidus for emboli is usually an atheromatous plaque, but emboli can also originate from lesions caused by FMD, radiation therapy, or aneurysms of the carotid vessels. A less common source is cardiac emboli, originating from an intracardiac thrombus associated with atrial fibrillation or myocardial infarction. Paroxysmal emboli, which originate from a deep venous thrombus that crosses from the venous to arterial systems via a septal defect in the heart, are a rare cause of cerebral ischemic attacks that should be considered in the very young.

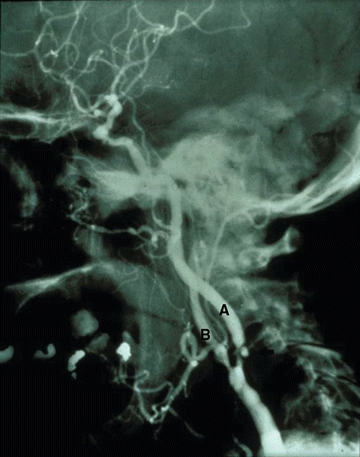

Although angiography has historically been considered the gold standard (Fig. 1), the initial diagnostic test is duplex ultrasonography to evaluate the extracranial carotid and vertebral arteries for occlusive lesions. The basic principle of this study is to assess anatomy, using real-time B-mode imaging, and flow dynamics, using quantitative pulsed wave Doppler, to determine the location and severity of disease. The grade of the lesion is characterized by increased velocity spectra recorded proximal to, and at, the point of maximum stenosis. Several studies have compared the accuracy of duplex ultrasound with arteriography and have determined a close correlation in stenotic estimations. Angiograms should be obtained where duplex cannot accurately determine the severity of the lesion. These situations include proximal common carotid or aortic arch lesions, contralateral carotid occlusion, high bifurcation of the carotid, and discrepancy in symptoms compared to the duplex findings. As technology advances, computed tomographic (CT) angiography and magnetic resonance arteriography (MRA) have become more useful diagnostic tools when these issues are encountered.

FIGURE 1 Cerebral angiography showing severe ICA stenosis (A) and stenosis of ECA (B).

Recommendation

Extracranial Duplex ultrasonography was recommended as well as head CT given the lateralizing TIA.

Extracranial Duplex Report

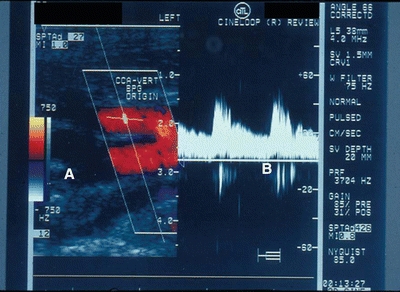

On the left side, the peak systolic velocity of 450 cm/s and end-diastolic velocity of 150 cm/s were noted at the proximal ICA. Here, significant spectral broadening of the waveform (Fig. 2B) and duplex real-time B mode (Fig. 2A) show a significant (>80% to 99%) stenosis of the proximal left ICA.

FIGURE 2 Carotid duplex typically has two components, an image (A) and a waveform that shows the velocity in the ICS (B).

Head CT Report

No evidence of acute cerebral ischemic infarct noted. On the left cerebral cortex, multiple small punctate lesions noted suggestive of old cerebral infarcts. Clinical correlation is indicated.

Diagnosis and Recommendations

This patient has a severely stenotic and symptomatic ICA lesion. Given her neurologic symptoms that have occurred in the past and this most recent episode, urgent carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and lifelong antiplatelet therapy (e.g., aspirin) are recommended. The patient inquires about the benefits of surgery, and she is advised of a 17% absolute risk reduction of stroke and a 71% relative risk reduction of at 18 months for surgery and antiplatelet therapy compared to antiplatelet therapy alone. She asks about the use of stents and is advised that the carotid stenting is currently approved only for octogenarian and patients with prohibitive operative risks. She is informed of the operative risks of death (0.6%), stroke (1%), cranial nerve injuries (less than 1%), wound complications (less than 0.01%), bleeding (less than 0.01%), and carotid restenosis (5%). The patient and her family were assured that the risks are significantly less than not operating.

Surgical Approach

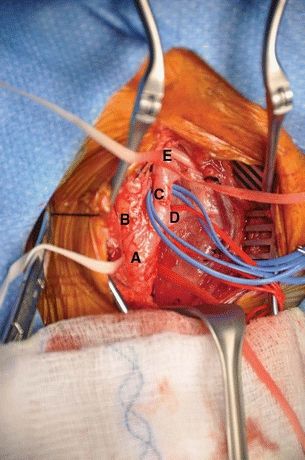

The patient is given general anesthesia, perioperative antibiotics are given, and the patient is placed in a “lawn chair” position. An incision is made anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and carried through the platysma. The internal jugular vein is identified and retracted laterally. The dissection is carefully continued around the common carotid artery (CCA) and control obtained with a vessel loop. The vagus nerve is identified posterior to the carotid artery. The dissection is continued superiorly to the superior thyroid artery and the external carotid artery (ECA). Control of these vessels is also established with vessel loops. Care is taken to avoid direct dissection of the carotid bifurcation. The ICA is further dissected superiorly, well above the distal aspect of the atherosclerotic plaque. The hypoglossal nerve is identified superior to the bifurcation (Fig. 3). Further exposure can be obtained superiorly with division of the digastric muscle tendon. However, care must be taken not to injure the glossopharyngeal nerve. The ICA is controlled with a vessel loop. Once all the vessels are controlled, the patient is systemically heparinized, and clamps are placed on the distal ICA, proximal CCA, proximal ECA, and superior thyroid artery. An arteriotomy is made on the anterior aspect of CCA extending on the anterior aspect of ICA. A shunt is inserted, secured by Rommel tourniquets, and the integrity of the shunt is evaluated with a handheld Doppler. The endarterectomy plane is then created, and the plaque is removed (Fig. 4). If intimal flaps are present, they are secured with tacking sutures. The arteriotomy is typically closed with a patch; however, an unusually large artery may require primary closure. Prior to completion of arteriotomy closure, shunt is removed. Back bleeding of the ICA is performed to remove any embolic potential (e.g., debris or air) before placing the last few sutures. Arterial flow is restored first to the ECA and then to the ICA. Duplex ultrasound scan is performed intraoperatively to identify any surgically correctable issues. With troublesome surface bleeding, sometimes a drain is inserted (Table 1).

FIGURE 3 Carotid artery exposure. A: Common carotid artery. B: Internal carotid artery. C: External carotid artery. D: Superior thyroid artery. E: Hypoglossal nerve.