The natural history and clinical course of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HC) is diverse, ranging from benign forms compatible with normal or extended longevity to adverse consequences requiring major interventions: surgical myectomy (or selectively alcohol septal ablation) for left ventricular (LV) outflow obstruction producing progressive heart failure; defibrillation and therapeutic hypothermia for cardiac arrest; implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) for prevention of sudden death; and heart transplant for refractory progressive heart failure in the absence of obstruction. Patients with HC may have their clinical course importantly influenced by either of these 3 major disease complications, but the occurrence of all 3 sequentially in a single patient over a 38 year period represents a notable and unusually aggressive form of HC. We present such a patient, prospectively followed and evaluated, who not only has incurred all major adverse consequences of HC but most importantly has survived due to effective treatment modalities available to patients with this disease.

Case Description

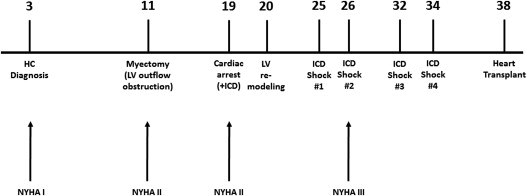

This patient was initially diagnosed with obstructive HC after a precordial murmur was detected at age 3 ( Figure 1 ). Her father had experienced a resuscitated cardiac arrest from HC and one brother (age 40) has HC with an uneventful course. Surgical myectomy was performed at age 11 years to relieve outflow tract obstruction (gradient, 100 mm Hg) and heart failure symptoms, associated with massive ventricular septal hypertrophy (wall thickness, 35 mm). Symptomatic improvement ensued briefly, but at age 19, the patient was successfully resuscitated from an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, and a secondary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was placed and subsequently replaced at ages 24, 27 (with biventricular pacing), and 33 years. A lead extraction at age 26 was complicated by a tear in the superior vena cavae which was repaired surgically.

Appropriate ICD interventions for sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF) occurred at ages 25 (during tennis), 26, and 32 (sitting at beach) and 34 years. In addition, 25 episodes of monomorphic VT terminated by anti-tachycardia pacing were tabulated, as well as hundreds of spontaneously aborted runs of nonsustained VT evident on ICD interrogation.

At age 26, the patient developed progressive heart failure in NYHA class III associated with adverse LV remodeling: maximum LV wall thickness = 11 mm; LV end-diastolic cavity dimension = 56 mm, and ejection fraction = 20%. Advanced heart failure symptoms persisted for the next 12 years refractory to a variety of pharmacologic agents, including beta-blockers, verapamil, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, sotalol, mexiletine, digoxin and spironolactone. Despite her significant functional limitation, the patient held sedentary jobs and performed treadmill exercise and yoga.

During this time period, LV remodeling progressed with cavity dimension increasing to 68 mm, and ejection fraction decreasing to only 15%. Peak oxygen consumption ranged from 19 to 21 ml/kg/min; cardiac index was 2.1 L/min/m 2 ; pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was 18 mm Hg, and brain natriuretic peptide was 3500 pg/ml. At age 38, the patient consented to heart transplant listing, and the operation was performed at Hospital of University of Pennsylvania. Postoperative recovery has been uneventful. Genetic testing documented a pathogenic mutation in the MYBPC3 gene (c. 2441_2443 delAGA).

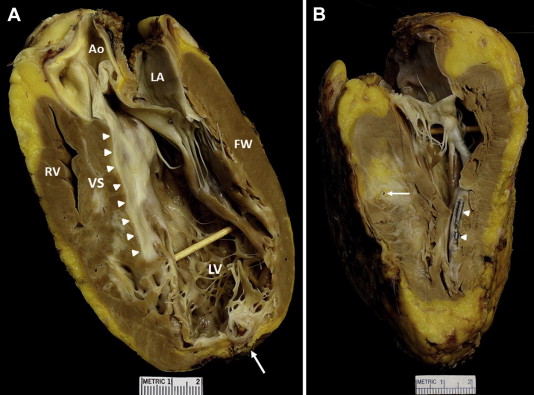

The explanted heart weighed 440 g. Ventricular septum was 14 mm in thickness, and the LV free wall was 16 mm ( Figure 2 ). The LV cavity was markedly dilated, but the right ventricle was normal-sized. Extensive areas of grossly visible scarring were present involving the ventricular septum and LV free wall. The mural endocardium of ventricular septum in apposition to the anterior mitral leaflet was severely thickened by fibrous tissue, extending distally and resulting (at least in part) from the myectomy performed 27 years earlier. The LV wall at the apex was thinned, aneurysmal, and fibrotic. The epicardial coronary arteries were free of atherosclerotic plaque, and the right and left main coronary arteries arose from the aorta in normal position.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree