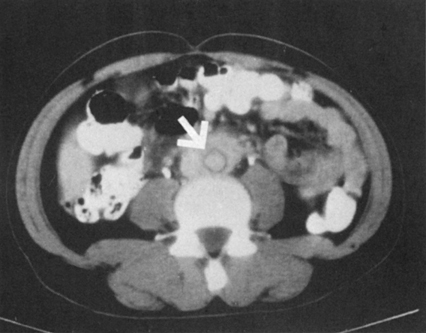

Inflammatory AAAs differ from other AAAs (Figure 1). Female patients generally account for less than 5% of patients with inflammatory aneurysms, whereas they ordinarily account for approximately one third of patients with routine AAA. Most patients with inflammatory aneurysms have symptoms of either back or flank pain. Inflammatory aneurysms tend to be more easily palpable at the time of diagnosis because of their large size. In addition, many of these patients have tenderness on palpation of the aneurysm. Patients with inflammatory AAAs tend to be younger (mean age, 62.2 years), whereas those with noninflammatory aneurysms are older (mean age, 68.2 years). Erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESR) are elevated in approximately 75% of patients with inflammatory aneurysms. If one could define the classic patient with an inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysm, the patient would be male, in his early 60s, with a large abdominal aneurysm, pain on palpation, weight loss, and an elevated ESR. Aside from the elevated ESR, this presentation can mimic an acute rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm or even an acute dissection.

Surgical Treatment of Inflammatory Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

Clinical Presentation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree