Chapter 26 Surgical Management of Femoral, Popliteal, and Tibial Arterial Occlusive Disease

This chapter discusses open surgical options for femoral, popliteal, and tibial arterial occlusive disease. Although some of these procedures may be performed occasionally for disabling intermittent claudication, the vast majority should only be performed for critical lower limb ischemia. This can be defined as sufficiently poor arterial blood supply to pose a threat to the viability of the lower extremity. Manifestations of critical ischemia are rest pain, ulceration, and gangrene. These manifestations typically occur because of arteriosclerotic occlusive disease of large, medium-sized, or small arteries, although other etiologies can produce or contribute to these ischemic conditions. For example, many nonvascular causes result in limb pain at rest; infection may cause or contribute to gangrene; and trauma and decreased sensation may produce ulceration. Although thromboembolism and other etiologies can produce acute critical limb ischemia, this chapter will address only chronic lower extremity ischemia owing to obliterative arteriosclerosis. Over the last 3 decades, it has become increasingly apparent that limbs that are threatened by this process almost always have multilevel occlusive disease, which often includes occlusions of arteries in the thigh, leg, and foot.1

Toe and Foot Amputations, Debridements, and Conservative Treatment

In addition, some patients with critical ischemia as manifest by mild ischemic rest pain or limited gangrene or ulceration can be treated conservatively with good foot care, antibiotics, analgesics, and limited ambulation.2 Conservative treatment is indicated in patients who might not tolerate revascularization procedures because of major comorbidities. Long periods of palliation and occasional healing of small ulcerations or gangrenous patches may occur in a few patients with critical ischemia.2

History of Aggressive Approach to Limb Salvage in Patients with Critical Ischemia Due to Infrainguinal Arteriosclerosis and Evolution of the Relationship Between Open Bypass Surgery and Angiographic Techniques and Endovascular Treatments

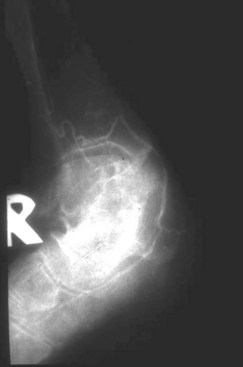

In the 1960s and 1970s, major below-knee or above-knee amputation was regarded as the safest and best treatment for gangrene and ulceration from arteriosclerotic occlusive disease below the inguinal ligament,3 despite the effectiveness of reconstructive arterial surgery (bypass and endarterectomy) for aortoiliac occlusive disease and despite some occasional positive results from femoropopliteal and even femorotibial bypasses. Because we had access to unusually good arteriography that visualized all the arteries in the leg and foot (Figure 26-1), we developed and promoted an aggressive approach to salvage threatened limbs, including those with extensive gangrene.4 More than 96% of patients with threatened limbs were subjected to an effort to save the limb. Only 4%, those with severe dementia or gangrene extending beyond the midfoot, were excluded. Only 6% of all patients with threatened limbs, when examined by this extensive arteriography, had no patent artery in the leg or foot that could serve as an outflow site for a bypass.4 With improvements in technique, this proportion of patients with arteries unsuitable for a bypass fell to 1% to 2%.1,5–11 Successful foot salvage was achieved in 81% to 95% of patients in whom bypasses were performed for the period that they lived up to 5 years.1,4 However, 52% of these limb salvage patients had many medical comorbidities and died, usually from cardiac causes, within the first 5 years after their initial bypass.4 More than two-thirds of the patients who lived beyond 5 years retained a useable limb and were able to ambulate beyond the 5-year time point.4 However, to maintain limb salvage many of these patients required some form of reoperation or reintervention, because they developed a failed (thrombosed) or failing (threatened but patent) graft from a lesion in their graft or its inflow or outflow tract.1,4,5 These worthwhile limb salvage results were in part achieved because of a myriad of improvements in the surgical techniques,1,4–11 development of methods to facilitate the many reoperations these patients required,12–14 and importantly because of improved anesthetic and intensive care management of these limb-salvage patients who often had advanced cardiorespiratory disease, poor kidney function, and diabetes. Collectively, these improvements made it possible to attempt limb salvage in almost every patient with a threatened limb and intact brain functions.1,4,9 In addition, many vascular centers throughout the world adopted these policies and were able to achieve equally good results.

Early Use of Endovascular Techniques (Angioplasty and Stenting) with Bypass Surgery

In the mid 1970s, some centers embraced the use of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) to treat these old, sick patients with threatened lower limbs.4 Initially, PTA was used to correct hemodynamically significant iliac artery stenosis. In most instances, it was combined with some form of infrainguinal bypass. However, as PTA techniques improved, balloon angioplasty was used to treat short iliac occlusions and some superficial femoral artery (SFA) lesions. Approximately 19% of patients with a threatened limb could be treated with PTA alone without an adjunctive bypass, whereas another 14% required some form of open surgical revascularization along with their PTA.1 These percentages increased and results improved with the introduction of iliac stents. As technical improvements in endovascular technology were developed, it became possible to use popliteal, infrapopliteal, and tibial PTA to facilitate the treatment of these limb salvage patients, to manage them less invasively, and to avoid some of the systemic and local complications of the lengthy and sometimes difficult distal operations in these old, sick patients.15,16,17 When possible, these endovascular techniques could be used to help in the treatment of patients with failed or failing bypasses, because reoperative procedures were often more difficult than primary bypass operations.1,4,18,19 Sometimes (in approximately 20% of patients) PTA eliminated the need for a secondary bypass: more often it made the secondary bypass simpler. In addition, we developed a number of unusual approaches to lower extremity arteries to facilitate reoperations by eliminating the need to redissect previously dissected arteries.12–1420

Current and Future Relationship Between Endovascular Treatments and Open Bypass Surgery

Although almost all experts will agree that there are still some indications for open surgical bypasses for limb threatening ischemia, there is wide variation in opinions about the proportion of patients with critical ischemia that will require an open bypass at some point in their disease process. At least 20% to 35% of patients with critical ischemia will require open surgery at some point in the course of their disease, although endovascular techniques continue to improve so that this proportion may decrease in the future. We also believe that such procedures will usually be indicated after failures of one, or usually more, endovascular treatments, although there are some patients with extensive foot gangrene, long occlusions, limited target outflow arteries, and a good greater saphenous vein in whom a bypass should be considered as the best initial treatment option.21,22 To some extent, such an option will depend on many factors, such as the age and health of the patient, the pattern of disease, and the skills of the involved interventionalist and surgeon. One real concern is that, as fewer bypasses will be required, fewer surgeons will be skilled in these demanding bypass techniques, particularly in the difficult circumstances in which they will be needed. Perhaps referral centers for bypasses should be established for the same reasons that such centers have been recommended for patients who require open thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair.

It has been recognized for many years that repetitive or redo procedures are an important component of care for patients with critical ischemia1,4,5; this will continue. Endovascular procedures may be used to salvage limbs after failed or failing open surgical bypasses.1,18,19 This tendency will increase as technology improves. Similarly, bypass operations or partially open thrombectomy will be required after early or late failure of endovascular treatment or prior bypasses in patients in whom no further endovascular options are available. Most of the 20% to 35% of critical ischemia patients who will require an open surgical bypass or thrombectomy will require it in such a setting.

Superficial Femoral Artery and Above-Knee Popliteal Occlusive Disease

With the introduction of improved techniques for crossing total occlusions, subintimal or intraluminal PTA can be used to treat most occlusions of the SFA and above-knee popliteal artery. Nitinol self-expanding stents and stent-grafts (Viabahn, W. L. Gore, Flagstaff, AZ) can be used as adjuncts to these procedures.23–25 When performing these procedures, care must be taken not to violate the principles and precautions outlined previously and to preserve important collateral vessels, such as the DFA. In the unusual instance when these endovascular interventions fail and cannot be restored to patency or when technical difficulty is encountered, a femoropopliteal bypass can be performed to the below-knee popliteal artery or tibioperoneal trunk via standard medial approaches.26 This bypass is best performed with a reversed greater saphenous vein harvested via skip incisions, although endoscopic vein harvest has been described27; however, this technique requires special equipment and technical expertise. In situ vein bypass offers no advantage in the femoropopliteal position. If the groin is heavily scarred or infected, the distal two-thirds of the deep femoral artery can be accessed directly in the thigh and used for bypass inflow (or outflow if a bypass ends in the groin).13 In circumstances in which the medial approaches to the popliteal artery are rendered difficult or impossible because of scarring or infection, both the above-knee and the below-knee popliteal arteries can be accessed via lateral approaches and used for bypass outflow.14 If this is done, the graft can be tunneled laterally in a subcutaneous plane. If patients do not have a saphenous vein or arm vein or if their veins are too small (<3.5 mm in distended diameter) or involved with preexisting disease 28 and they require a femoropopliteal bypass, a 6-mm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) conduit may be used.29 If this is done or if a vein is used, duplex surveillance is warranted and reintervention is justified for a failing (threatened) graft. However, if the graft has failed (thrombosed), reintervention is indicated only if the failure results in critical ischemia, which occurs in approximately 65% of cases in whom the original bypass was performed for critical ischemia.12