Chapter 49 Surgical Management of Chronic Venous Obstruction

Reconstruction of the occluded iliofemoral vein or the inferior vena cava (IVC) may be required in patients with post-thrombotic venous occlusion and who exhibit signs and symptoms of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI). Reconstruction of large veins may also be needed in patients with acute traumatic or iatrogenic venous injuries or in those who undergo excision of primary or metastatic malignant tumors invading the IVC or the iliac veins. May-Thurner syndrome (occlusion or stenosis of the left common iliac vein resulting from compression by the overriding right common iliac artery) is a cause of acute or chronic left iliac vein obstruction that is likely much more frequent than previously thought.1 It can be responsible for CVI in up to one third of the patients with CVI.

Endovascular treatment for iliocaval obstruction has progressed rapidly, and venous stenting is currently the primary choice for treatment of benign iliac, iliofemoral, or iliocaval venous occlusions in patients who fail conservative compression therapy. In the last 2 decades, results of open surgical reconstructions have improved, and symptomatic patients who are not candidates or who fail endovascular reconstructions can be treated with venous bypasses to relieve venous outflow obstruction.2 A thorough preoperative evaluation to identify significant venous outflow obstruction in these patients is essential.

Etiology

Venous outflow obstruction can be the result of primary venous disease, like May-Thurner syndrome,3 or it can be the result of a previous acute deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Uncommon causes include retroperitoneal fibrosis; iatrogenic, blunt, or penetrating trauma; placement of IVC filter, congenital venous anomalies such as deep vein agenesis or hypoplasia, and benign or malignant tumors. May and Thurner observed secondary changes, such as an intraluminal web or spur, in the proximal left common iliac vein in 22% of 430 autopsies. The most frequent primary malignant tumor originating from large veins is venous leiomyosarcoma; secondary tumors invading the vena cava include adenocarcinoma or liposarcoma. Renal carcinoma may extend into the IVC, and the tumor thrombus in some patients may reach all the way into the right atrium, although invasion of the wall of the IVC is rare. Congenital suprarenal caval occlusion can occur because of webs or caval coarctation that may also develop with associated hepatic vein occlusion (Budd-Chiari syndrome).4,5

Presentation

Limb swelling and pain during and after exercise that is relieved with rest and leg elevation (venous claudication) is the typical presentation of patients with chronic venous obstruction owing to previous DVT, PTS, or obstruction of common iliac veins (May-Thurner syndrome).6 Patients with obstruction may also have symptoms similar to those associated with primary valvular incompetence, such as varicosity, edema, skin changes, or venous ulcers; however, claudication and edema are usually more severe with venous obstruction, and relief with limb elevation is not as pronounced.

Depending on the extent of the collateral circulation, patients with outflow obstruction will have pain, swelling, and heaviness of the limb, and the most severe forms of venous obstruction can interfere with the viability of the limb. Obstruction alone can also result in skin changes and venous ulcerations. In the Mayo Clinic, experience with 64 venous reconstructions performed in 60 patients with benign disease, mean duration of symptoms was 6 years (Table 49-1).

TABLE 49-1 Clinical Symptoms in 60 Patients Undergoing Venous Reconstructions for Benign Disease at the Mayo Clinic

| Symptom | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Venous edema | 56 (94%) |

| Venous claudication | 54 (90%) |

| Edema and claudication | 50 (84%) |

| Healed ulceration | 8 (13%) |

| Active venous ulcers | 12 (19%) |

From Garg N, Gloviczki P, Karimi KM, et al: Factors affecting outcome of open and hybrid reconstructions for nonmalignant obstruction of iliofemoral veins and inferior vena cava. J Vasc Surg 53(2):383–393, 2011.

Investigations

Duplex Scanning

Venous duplex scanning should be performed in all patients with symptoms of CVI to help to define the location, cause, and severity of the underlying problem. The test is safe, noninvasive, cost-effective, and reliable and is recommended as the first diagnostic test for all patients with suspected CVD.7–9 Duplex scanning is excellent for evaluation of both infrainguinal venous obstruction and valvular incompetence.10

Plethysmography

Venous plethysmography is rarely used, but it is a useful tool that provides information on venous function in patients with CVI and is a complementary examination to duplex scanning. Plethysmography quantifies venous reflux and obstruction and has been used to monitor venous functional changes and assess physiologic outcome of surgical treatments.11,12 These studies are especially helpful in patients with suspected outflow obstruction but normal duplex findings or in those suspected of having venous disease because of calf muscle pump dysfunction, but no reflux or obstruction noted on duplex scanning. Air or strain gauge plethysmography is designed to evaluate the global leg hemodynamics by measuring reflux, obstruction, and calf muscle pump function. Decreased vein wall compliance in patients with PTS may interfere with proper evaluation of calf muscle pump function.

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Venography

Early venous disease (C1-2) rarely requires advanced imaging studies than duplex ultrasonography. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging have progressed tremendously in the last decade, and they provide excellent three-dimensional imaging of the venous system. Both modalities are suitable for identifying pelvic or iliac venous obstruction in patients with lower limb varicosity, when proximal obstruction or iliac vein compression (May-Thurner syndrome) is suspected.13 Venous phase examination will help to identify any obstructing mass or tumor and provides sufficient information in most patients about venous anatomy, obstruction, or stenosis.

Contrast Venography and Hemodynamic Studies

Ascending or descending (or both) contrast venography for CVI is performed only selectively in patients with deep venous obstruction, postthrombotic syndrome, thrombotic or nonthrombotic pelvic vein obstruction (May-Thurner syndrome), pelvic congestion syndrome, nutcracker syndrome, vascular malformations, venous trauma, or tumors or if invasive treatment is planned. Descending venography is used to study associated venous valve incompetence with Valsalva maneuver is classified to grade the severity of reflux (grade 1 to 4: 1 = to upper thigh; 2 = to distal thigh; 3 = popliteal reflux; 4 = reflux to tibials and perforators).14,15 This test has been much less frequently used in recent years. Ascending venography is performed in a standing position to evaluate patency of the superficial or deep venous system, or both. Ascending venography is useful as a map of the deep veins of the limb; it defines the sites of obstruction and images the collateral venous circulation and the patterns of preferential flow.

Contrast venography is routinely used in CVD to perform endovenous procedures, such as angioplasty or venous stenting or open venous reconstructions. A pressure gradient across iliofemoral obstruction at rest in the supine patient (3 mm Hg) or 10 mm Hg after exercise is indicative of functional venous obstruction. Exercise consists of 10 dorsiflexions of the ankles or 20 isometric contractions of the calf muscle. Arm or foot venous pressure test and ambulatory venous pressure measurement in a dorsal foot vein are additional tests that can be performed. Detailed descriptions and techniques for these tests are provided in the consensus statement.16

Intravascular Ultrasound

Recent assessment of patients with iliofemoral venous occlusion suggested that intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is useful for evaluation of patients with suspected or confirmed iliac vein obstruction. IVUS can be used in veins with obstruction without occlusion to assess the venous wall morphology and mural thickness, identify trabeculations and recanalization, frozen valves, and external compression. Some of these lesions, as emphasized by Neglen and Raju,13 are not seen with conventional contrast venography; IVUS provides measurements in assessing the degree of stenosis. In addition, IVUS confirms the position of the stent in the venous segment and the resolution of the stenosis.13

Treatment

Conservative Management

Symptoms of chronic deep venous obstruction should be first treated with compression therapy and local wound care of venous ulcerations, if there are any. Compression is recommended in addition to lifestyle modifications that include weight loss, exercise, and elevation of the legs whenever possible. The rationale of compression treatment is to compensate for the increased ambulatory venous hypertension. Pressures to compress the superficial veins in supine patients range from 20 to 25 mm Hg, whereas in the upright position, pressures of 35 to 40 mm Hg have been shown to narrow the superficial veins, and pressures higher than 60 mm Hg are needed to occlude them.17 Ambulatory compression techniques and devices include elastic compression stockings, paste gauze boots (Unna boot), multilayer elastic wraps, dressings, and elastic and nonelastic bandages and nonelastic garments. Pneumatic compression devices, applied primarily at night, are also used in patients with refractory edema and venous ulcers.18 Compression garments result in variable degrees of success and mandate strict patient compliance, which in a hot climate can be both distressing and difficult. Patients with persistent disabling symptoms, such as venous claudication, severe swelling, and nonhealing or recurrent ulcers not responding to conservative treatment, should be considered for endovascular or open surgical reconstruction.

Endovascular Treatment

Iliac or iliocaval stenting has become the primary treatment for chronic nonmalignant venous occlusions. Early and midterm results of endovascular techniques, most frequently using self-expandable stents, such as angioplasty and stenting, have been good. Techniques and results are discussed further in Chapter 50.

Hybrid Reconstruction

In patients with common femoral vein obstruction and proximal disease, conventional venous stenting is frequently not possible. Endovenous recanalization and stent placement, however, can be combined in selected cases with femoral vein endophlebectomy and patch angioplasty, using bovine pericardial patch. Balloon angioplasty and stenting is performed before or at completion of the patch angioplasty. Jugular vein access is obtained for retrograde recanalization as an alternative to or in combination with femoral access. The stent is extended proximally to the healthy vein and across the inguinal ligament distally. With recent experience, the distal end of the stent can be extended into the venous patch.2 Others have reported good patient outcomes with the hybrid technique, using saphenous vein patch for closure.19

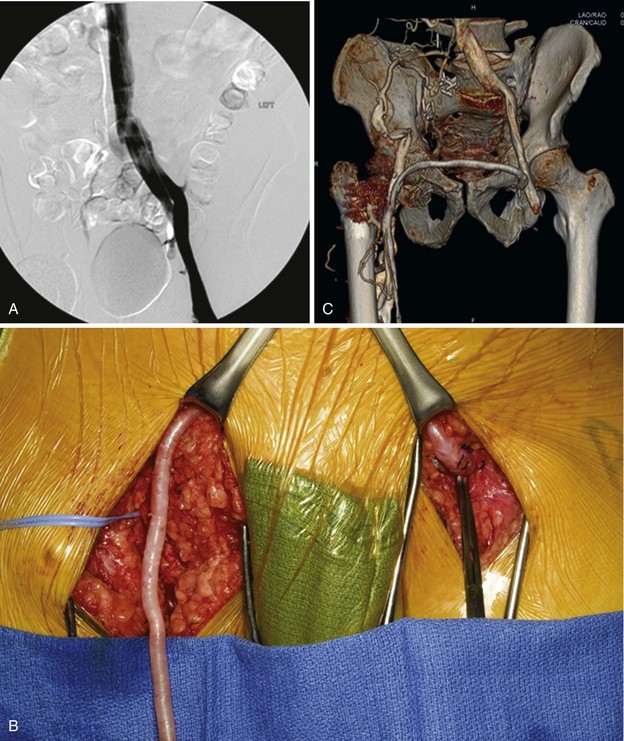

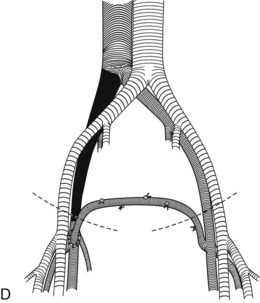

Crossover Saphenous Vein Transposition (Palma Procedure)

Patients with symptomatic unilateral iliac vein obstruction are candidates for Palma procedure (Figure 49-1). With this technique, the contralateral saphenous vein is used for a crossover bypass to decompress venous congestion in the affected limb. The common femoral vein on the affected side is exposed first through a 6- to 8-cm long longitudinal groin incision. The collateral veins should be preserved if possible. The great saphenous vein of the contralateral leg is dissected through a 3- to 5-cm incision made in the groin crease, starting just medial to the femoral artery pulse. Tributaries of the saphenous vein are ligated and divided, and the saphenous vein is mobilized in a length of 10 to 12 cm. A short, second upper-thigh incision is made to dissect a 20- to 25-cm long portion of the saphenous vein. The vein is ligated distally, and it is divided proximal to the ligature and pulled up to the groin incision. Alternatively, endoscopic harvesting of the saphenous vein can also be performed, although this likely results in increased vein wall damage that could affect patency.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree