At first glance, surgical mediastinal staging may appear to be a mundane and lackluster topic, extensively reviewed with little new information to be added. However, beneath this surface lie many nuances and issues that often lead to confusion, misinterpretation of data, and erroneous conclusions. Furthermore, there are many new developments, both with respect to surgical techniques and in regard to alternative roaches to mediastinal evaluation. Because mediastinal staging remains a key factor in selecting a treatment approach for patients with lung cancer, an understanding of the issues and developments is crucial to achieve optimal clinical outcomes.

Definition of the role of surgical mediastinal staging is complex and depends on many characteristics of the patients being considered. In fact, lack of attention to details of the patients involved is probably the major factor leading to inappropriate application of results from one population to a different cohort. The patients may have undergone minimal imaging (chest x-ray [CXR] or computed tomography [CT]) or more sophisticated imaging (positron emission tomography [PET] or PET/CT). Whether the patient has undergone a careful clinical evaluation for signs and symptoms of distant metastases is often glossed over, and patients may (e.g., those with symptoms of metastases or asymptomatic clinical stage III [cIII]) or may not (e.g., asymptomatic cI) have an indication for extrathoracic imaging for metastases. It is important to note whether the patients have normal-sized or enlarged mediastinal nodes. Finally, results of a procedure done as a staging test are very different from a procedure done merely to make a diagnosis (often including many patients that do not have lung cancer). A lack of awareness of these issues often leads to inappropriate application of the results of a study to a different type of patient.

Even when the focus is limited only to surgical mediastinal staging, there are issues regarding the extent and quality of the procedure. Newer techniques of surgical mediastinal staging can provide a much more accurate assessment, but the biggest issue is simply whether traditional mediastinoscopy is performed according to accepted standards. It is clear that there are frequent breaches in quality that are likely to have serious consequences for patients,

1 although this has not been studied in detail. Furthermore, there are differences in pathologists’ assessment of nodes, and newer techniques can provide more sensitive assessments (i.e., immunohisto chemistry of micrometastases). Having said this, the prognostic value of such pathologic investigations is questionable at present.

2,

3,

4Many alternative techniques have been developed to allow less invasive, “nonsurgical” mediastinal tissue staging. These are discussed in more detail in

Chapter 31, but how these techniques can be integrated is discussed here. It is important not to view the various techniques of tissue staging as competitive. To a large extent, the techniques have been used in different patient populations (i.e., anatomic location of particular enlarged or normal-sized nodes), making a simple comparison of test performance characteristics inappropriate. How the different procedures best complement one another depends on patient characteristics, the primary question to be addressed (i.e., to rule in cancer or to rule out cancer), and the level of proficiency available with a particular approach.

Finally, the role of surgical mediastinal staging is a matter of judgment. No test can be expected to yield perfect results, so it becomes a question of how much uncertainty one is willing to accept. This threshold is influenced by the risk and morbidity of the procedures involved. Although mediastinoscopy is done as an outpatient procedure in most centers and is associated with low morbidity (2%) and mortality (0.08%), it is somewhat invasive.

5 It is proposed that in general, invasive staging is justified if there is a >10% chance of error in the mediastinal stage from imaging alone, and noninvasive testing (i.e., PET) for a >5% chance of error. Performing a test for a low prevalence of disease runs the risk of either a test-related complication or an erroneous result without a high chance of benefiting from the test.

SCOPE

This chapter focuses on surgical methods of mediastinal staging, namely, mediastinoscopy and variation of this technique (videomediastinoscopy, video-assisted mediastinal lymphadenectomy [VAMLA], and transcervical extended mediastinal lymphadenectomy [TEMLA]). The chapter also includes a discussion of thoracoscopic approaches as well as the Chamberlain procedure (anterior mediastinotomy). The focus is on primary staging of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Restaging of the mediastinum after induction therapy is not covered thoroughly. In addition, mediastinal procedures done only to make a diagnosis (i.e., lymphoma, thymoma) are not discussed.

DEFINITIONS

It is important to clearly define the major terms used to avoid confusion. Pathologic staging, according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), refers to the stage after surgical resection and complete pathologic evaluation of the specimen and any other tissues submitted. Clinical stage is the stage as determined by any and all information that is available prior to resection. Thus, clinical stage can involve imaging (radiographic staging) or biopsies such as transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) or a mediastinoscopy (tissue staging). Although mediastinoscopy is considered a surgical procedure and involves a pathology report, it is still part of clinical staging.

Various parameters can be used to assess the reliability of a test, including sensitivity, specificity, and false-n egative (FN) and false-positive (FP) rates (typically expressed as a percentage). The latter two measures are sometimes expressed in a less intuitive manner as the converse, known as the negative predictive value (NPV = 1 − FN rate) or positive predictive value (PPV = 1 − FP rate). Sensitivity and specificity are derived from patient populations in whom the true disease status is already known, who either all have or do not have the condition in question. These parameters provide data about how often the test will be positive or negative for these respective populations. Thus, these measures provide information about the test, because the disease status has already been determined in the patients. In theory, these measures can be used to compare different tests, but only if the patient populations in which the tests are used are the same. Unfortunately, particularly with regard to invasive staging tests, the patients selected for diffe rent tests are not the same, limiting the value of the measures of sensitivity and specificity.

The FN and FP rates of a test are of much greater practical use to the clinician, who must interpret the reliability of a test result (positive or negative) in an individual patient. The clinician does not know the true disease status of the patient; he/she only knows that the patient has a negative or a positive test result. Interpretation of a test result for an individual patient requires knowledge of the FN or FP rate. It is important to point out that the FN or FP rate of the test cannot be estimated from the sensitivity or specificity, because each of these is derived from different formulas. This is a common misconception that frequently creates confusion and inappropriate interpretation of test results. The only exception to this fact is in the case of “perfect” test performance: a sensitivity of 100% does, in fact, imply an FN rate of 0, and a specificity of 100% implies an FP rate of 0.

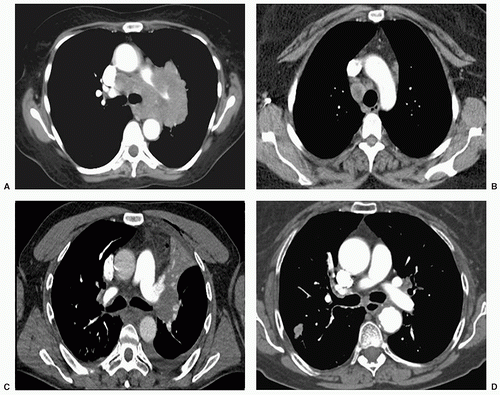

In general, patients with lung cancer can be separated into four groups (

Fig. 29.1) with respect to intrathoracic radiographic characteristics of the primary tumor and the mediastinal nodes.

5,

6 Briefly, the groups are patients with extensive mediastinal infiltration (radiographic group A), those with enlargement of discrete mediastinal nodes (radiographic group B), patients with normal mediastinal nodes by CT but a central tumor or suspected N1 disease (radiographic group C), and those with normal nodes, mediastinal nodes, and a peripheral cI tumor (radiographic group D).

A widely accepted definition of normal-sized mediastinal lymph nodes is a short-axis diameter of ≤1 cm on a transverse CT image.

6 Discrete nodal enlargement implies that discrete nodes are seen on the CT scan and are defined well enough to be able to measure their size (and are >1 cm). Mediastinal infiltration is present when there is abnormal tissue in the mediastinum that does not have the appearance and shape of distinct lymph nodes, but instead has an irregular, amorphous shape.

6 In this case, it is difficult to distinguish discrete nodes and impossible to come up with a measurement of the size of nodes. This occurs when multiple nodes are matted together to the point where the boundary between them is obscured and can be assumed to involve extensive extranodal spread of tumor. It may progress to the point where mediastinal vessels and other structures are partially or completely encircled. Finally, the distinction between a central versus a peripheral tumor has also not been codified, but most authors consider any tumor in the outer two thirds of the hemithorax to be peripheral.

6

TECHNIQUE AND OUTCOMES OF STANDARD MEDIASTINOSCOPY

Mediastinoscopy has been the mainstay of invasive mediastinal staging for the past 40 years. The procedure is performed in the operating room, usually under general anesthesia. It is currently done as an outpatient in most U.S. centers.

7,

8,

9 Mediastinoscopy involves an incision just above the suprasternal notch, insertion of a mediastinoscope alongside the trachea, and biopsy of mediastinal nodes. Rates of morbidity and mortality as a result of this procedure are low (2% and 0.08%).

10 Right and left high and low paratracheal nodes (stations 2R, 2L, 4R, 4L), pretracheal nodes (stations 1, 3), and anterior subcarinal nodes (station 7) are accessible via this approach. Node groups that cannot be biopsied with this technique

include posterior subcarinal (station 7), inferior mediastinal (stations 8, 9), aortopulmonary window (APW) (station 5), and anterior mediastinal (station 6) nodes.

The average sensitivity of mediastinoscopy to detect mediastinal node involvement from cancer is approximately 80%, and the average FN rate is approximately 10% to 15% (

Table 29.1), as has been compiled in several systematic reviews.

5,

11 Several authors have shown that approximately half (42% to 57%) of the FN cases were caused by nodes that were not accessible by the mediastinoscope.

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17 The specificity and the FP rates of mediastinoscopy are reported to be 100% and 0, respectively. Strictly speaking, these values cannot really be assessed because patients with a positive biopsy were not subjected to any further procedures (e.g., thoracotomy) to confirm the results. The results of mediastinoscopy are fairly consistent among studies.

5Quality of Surgical Staging The results cited in the preceding paragraph outline the experience in dedicated thoracic centers with a specific interest in thoracic surgery. However, there are indications that what is practiced more broadly is not the same.

1,

18 In the United States, many patients with lung cancer undergo resection either by general surgeons or cardiothoracic surgeons whose primary scope of practice is cardiac surgery. A fair amount of data suggests that both short-and long-term outcomes of patients with lung cancer are affected by the quality of care as well as the extent of specialization in thoracic surgery.

19,

20,

21

With regard to mediastinal staging, it seems obvious that the FN rate depends on the diligence with which nodes are dissected and sampled at mediastinoscopy. Ideally, five nodal stations (stations 2R, 4R, 7, 4L, 2L) should routinely be examined, with at least one node sampled from each station unless none are present after

actual dissection in the region of a particular node station. The difference between this and what is actually done is underscored in a report by Little et al.

1 Analysis of national data in the United States on 11,688 surgically treated patients disclosed that only about half of the patients underwent either PET or mediastinoscopy to define the status of mediastinal nodes. Even more striking was the fact that in more than half of the mediastinoscopies performed,

not even a single mediastinal node was biopsied. Finally, in almost half of the patients, no mediastinal nodes were biopsied at the time of thoracotomy.

The survival of patients with intraoperatively discovered “surprise N2” disease discovered at the time of resection varies dramatically according to the extent of preoperative staging that was undertaken.

22 Extrapolation of this data suggests that the differences between good-and poor-quality preoperative staging overshadow any differences that might be realized by integration of newer alternative techniques (esophageal ultrasound-guided needle aspiration [EUS-NA], endobronchial ultrasound-guided needle aspiration [EBUS-NA]). It is probably more important to have expertise in at least one technique of invasive mediastinal staging by a dedicated individual than to quibble about the relative value of one technique versus another. PET alone is clearly not adequate to stage the mediastinum, even in centers with a dedicated interest and expertise in PET for lung cancer.

6,

23,

24,

25The recommendation that five nodal stations (stations 2R, 4R, 7, 4L, 2L) should routinely be examined at mediastinoscopy has been endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP),

5 the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS).

26 The ESTS recommends, but does not mandate, that sampling of stations 2R and 2L be done.