Fig. 5.1

Central cannulation. Ao aorta, PV pulmonary vein, LA left atrium, RV right ventricle, LV left ventricle

5.2.2 Surgical Technique

The site for the cannulation of the aorta is proximal to the origin of the innominate artery on the anterior aortic surface (Fig. 5.1). Two purse-string sutures are placed, a stab wound is made within the sutures, and the cannula is then placed in the distal ascending aorta. The two purse-string sutures are secured through two tourniquets that will be kept in the patient’s thorax until decannulation (Fig. 5.2). The cannula tip must be completely within the lumen and positioned in order to direct the flow to the mid transverse aorta. It is suggested to place the cannula in an area where the atherosclerotic disease is minimal or absent.

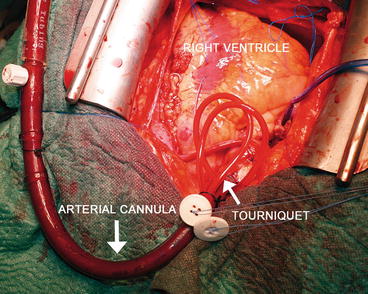

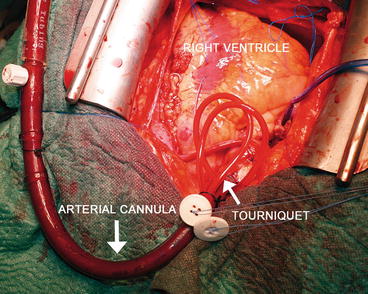

Fig. 5.2

Central cannulation: the arterial cannula. The two purse-string sutures are secured through two tourniquets that will be kept in the patient’s thorax

The venous cannula is introduced through the right atrial appendage so as to allow its tip to rest in the mid-right atrium (Fig. 5.1). Before the cannula placement, a single purse-string suture is positioned, the right atrial appendage is opened, and the cannula is then inserted. Again, the suture is secured with a tourniquet. During venous cannulation, the surgeon should be careful about displacement or damage of central venous or pulmonary arterial monitoring catheters; conversely, catheters could compromise the function of venous cannula.

If an ECMO support is required after a case of difficult weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass, arterial and venous cannulas are already placed. The surgeon should maintain the cardiopulmonary bypass cannulas, but he should change the circuit. First, it is necessary to stop the extracorporeal circulation, and after that to clamp the cannulas, deconnect them from the cardiopulmonary bypass circuit, connect them to the ECMO circuit, remove the clamps from cannulas, and start the new extracorporeal support.

In the end, the surgeon could introduce an apical or pulmonary vent (Fig. 5.1) to unload the left ventricle and could insert a left atrial pressure monitoring line through the right superior pulmonary vein.

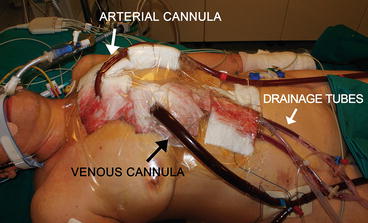

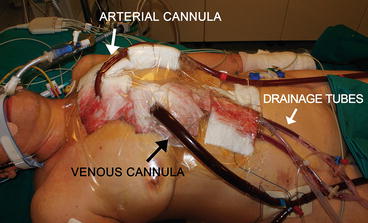

At the end of a cardiac surgery intervention, after an accurate hemostasis of the heart and other tissues, mediastinal and pleural drainage tubes are positioned and the sternum is usually closed. In patients undergoing ECMO support, chest closure is not always possible. In most of such cases, it might happen that the sternum could not be closed because of the depressed cardiac function and the presence of the cannulas. When the sternum, subcutaneous tissue, and skin are left unsutured, an occlusive dressing is applied to the anterior chest wall (Fig. 5.3). Whenever possible, the skin can be sutured with Donati stitches, or a sheet of artificial tissue can be sutured to the skin edges so as to protect mediastinal tissues and prevent infections. However, new cannulas have been designed so as to be tunneled to the subcostal abdominal wall allowing the chest to be completely closed [2].

Fig. 5.3

Central cannulation. An occlusive dressing is applied to the anterior chest wall to guarantee the protection of the mediastinic structures

When decannulation is required, the patient is conducted to the operating room where the chest will be opened again. The cannulas are removed while the purse-string sutures are tied with a hemostatic effect. Primary chest closure is determined at the discretion of the surgeon.

5.2.3 Perioperative Management

The proper position of the cannula is essential to provide an adequate ECMO blood flow. After central cannulation, intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography is the first technique used to confirm appropriate cannula positions and ventricular decompression before chest closure. During postoperative days, routine chest radiograph could be used to detect any change in the positions of the cannulas.

Nursing care for patients with ECMO central cannulation is more complex than the one that deals with peripherally cannulated patients. A special care must be provided to the chest dressing and cannula handling. Chest drainage tubes must be monitored very often. Every change of the position of the patient must be carefully accomplished, and patient’s transport is more difficult than peripherally cannulated patients.

5.2.4 Complications and Disadvantages

Despite the advantages of the central cannulation, it is though related to important complications during cannulation and postoperative period. Major complications of ascending aorta cannulation include injury or dissection of the aortic anterior and posterior wall; misplacement of the cannula tip against the aortic wall, towards the valve, or in an arch vessel; emboli; and inadequate or excessive cerebral flow. Otherwise, venous atrial cannulation is associated to atrial arrhythmias, atrial or caval tears and bleeding, and air embolization. Local complications that may occur during and after decannulation also include bleeding, atrial or aortic injuries, and pseudoaneurysm.

Limb ischemia is generally associated to peripheral cannulation, but it can also be observed with the central cannulation. In such a situation, peripheral ischemia is no local complication but more likely an embolic phenomenon associated with the presence of aortic atheromas.

The main drawbacks of central cannulation are the open chest and the high risk of bleeding. Patients with central cannulation, compared to patients with peripheral cannulation, had a 6-fold higher rate of reoperation and a 3-fold higher rate of bleeding from cannulation sites [3]. Such conditions can be explained because the cannulas are inserted into a constantly moving organ, and the patients had a sternotomy with large areas of raw tissue. The need for repeated operations and the evacuation of bleeding with the central cannulation contribute to the increase in terms of costs and risks for the patient [3]. Mediastinitis is more frequent in central cannulation because of the difficult management of the open chest. Moreover, patients with central cannulation could not be extubated; transports and nursing care are more difficult as already reported.

5.3 Peripheral Cannulation

5.3.1 Indications

ECMO is a well-established treatment also when cardiac surgery is not involved. Peripheral cannulation does not require an open-chest approach so it results in a quicker procedure. It is useful if immediate support is needed and if ECMO is started in different hospital situations. It is recommended in case of primary cardiogenic shock, acute myocardial infarction, cardiopulmonary arrest, high-risk PTCA, myocarditis and cardiomyopathy, pulmonary hypertension, intractable arrhythmias, and respiratory failure. Moreover, peripheral cannulation allows easier nursing cares and easier and safer transports of the patients, and the patients can be extubated even if ECMO support is still ongoing. The cervical vessels and the brachiocephalic artery are the best peripheral cannulation sites in neonates and children weighing less than 15 kg. Groin cannulation of the common femoral artery and vein often provides efficient venous drainage and perfusion for larger children and adults. The axillary and iliac arteries represent additional sites that could be used.

5.3.2 Femoral Vessels

5.3.2.1 Femoral Artery: Surgical Technique

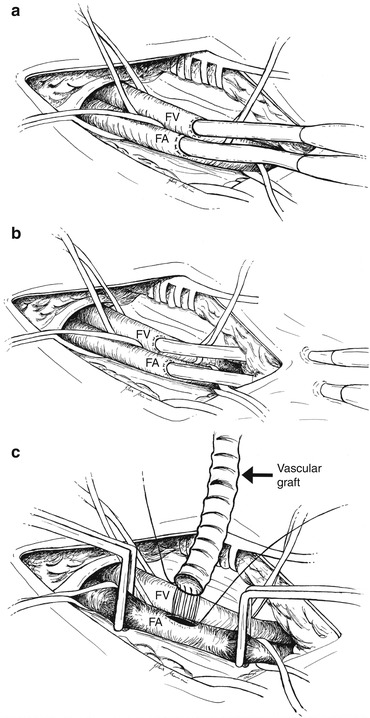

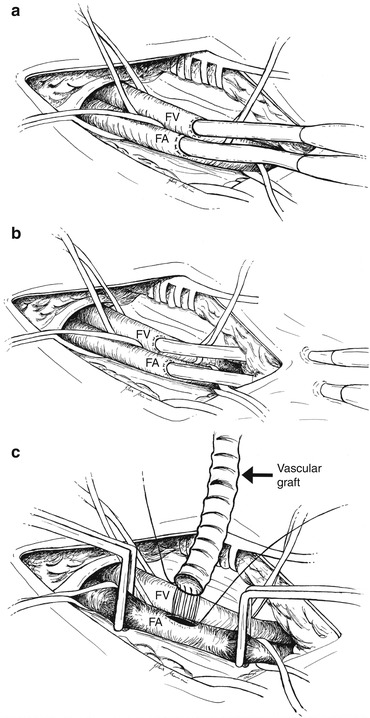

Femoral artery cannulation is probably the most common approach for ECMO implantation because of its ease and the large diameters of this vessel. Femoral cutdown is the traditional surgical approach (Fig. 5.4a). A transverse or longitudinal skin incision is made over the femoral vessels and below the inguinal ligament. Dissection is undertaken so as to isolate the femoral artery and vein, proximal and distal control of each vessel is obtained through loops, and a purse-string suture is placed. After heparinization, the common femoral artery is clamped proximally and distally, and a transverse arteriotomy is made, leaving the posterior one third of the artery intact. A 15–21-Fr arterial cannula is directly inserted. Some authors prefer the use of an 8–10-mm PTFE or Dacron “chimney graft” sewn in an end-to-side way on the arterial vessel [4] (Fig. 5.4c). Afterwards, the chimney graft can be tunneled under the skin or extended over it; the cannula is then inserted and the wound is closed. The cannula position must be fixed to the skin with multiple ligatures. Such a technique is recommended in patients with small vessels likely to be occluded by arterial cannulas (children, thin adults, peripheral artery disease), patients in whom ischemia develops after percutaneous cannulation, or patients who undergo cannulation in the operating room with vessels already exposed for CPB [5, 6]. The technique lowers the risk of distal leg ischemia and vessel dissection and simplifies decannulation. Unfortunately, this approach requires a longer preparation time, and it cannot be used in case of emergency. In such a situation, a pre-sealed short vascular prosthesis can be bevelled at its distal end and passed over the cannula. The cannula is then inserted into the vessel, and when ECMO is stable the vascular prosthesis around the cannula is lowered onto the femoral artery. In this moment, the prosthesis is anastomosed to the artery, and the arterial cannula can be withdrawn carefully, positioning its distal end within the prosthesis at the level of the anastomosis [7]. In the semi-Seldinger technique (Fig. 5.4b), a small transverse incision is made over the femoral artery and deepened so as to expose a short length of the common femoral artery. The arterial puncture needle is introduced via a separate stab incision 2 cm distal to the incision, and it is inserted into the artery under direct vision. The following steps are the same as described for Seldinger technique. A purse-string suture on the artery could be used to assure hemostasis, and the wound is then closed. This method of insertion allows the arterial cannula to lie nearly parallel to the artery and prevents over-angulation and kinking at the entry site.

Fig. 5.4

Femoral vessel surgical cannulation. (a) Direct cannulation of the femoral vessels after surgical isolation of the vessels. (b) Semi-Seldinger technique: the cannulas are introduced via a separate stab incision 2 cm distal to the main incision. (c) Chimney graft technique: a PTFE or Dacron vascular graft is sewn in an end-to-side way on the femoral artery. FA femoral artery, FV femoral vein

After weaning from bypass, the operative field is opened again. The cannulas are removed and the cannulation sutures tied; running or interrupted sutures are placed as appropriate. To ensure peripheral perfusion, the arterial vessel is palpated distal to the former cannulation site immediately after decannulation. In case of distal malperfusion or pulselessness, reconstructive procedures are performed. If a chimney graft is present, after the cannula removal, the side graft can be closed with staples or a snare about 1 cm above the anastomosis and the residual part can be cut. If ECMO is still necessary, a new graft may be sutured to the stump of the old graft [4]. In cases of percutaneous cannulation, some authors suggest an open repair of the vessel in order to prevent bleeding and hematoma development [8]. Open repair of vessels also allows evaluation for potential areas of stenosis and ability to perform patch angioplasty if needed [8].

5.3.2.2 Femoral Vein: Surgical Technique

Femoral vein cannulation is more often percutaneously performed. Surgical isolation is performed when percutaneous approach fails or if femoral vessels are already exposed. Some authors suggest the cannulation of right femoral vein because of the easier placement of the cannula up to the right atrium, due to the relationship of the iliac vein and inferior vena cava to the iliac crest [9]. Some others suggest the cannulation of the contralateral femoral vein as opposite to the cannulated femoral artery to avoid a cluttered field [10]. The skin incision and the dissection techniques are the same as described above. Venous cannulation is performed first. A circumferential purse-string suture is placed in the anterior wall of the vein; the common femoral vein is then clamped proximally and distally. A venotomy is made within the purse string, the venous cannula is inserted, and the proximal and distal clamps are removed. The cannula is finally advanced up to the right atrium. Once properly positioned, the venous cannula is fixed, the arterial cannulation is performed, and the wound is closed. Cannula diameter size is from 19 to 25 Fr.

5.3.2.3 Limb Ischemia and Distal Perfusion: Open Access

Ischemic complications using different approaches for femoral cannulation varied between 10 and 70 % [11]. Peripheral arterial disease is an independent predictor of vascular complications, and assessment of ankle–brachial index before ECMO implantation is recommended whenever possible [11]. During ECMO support a nursing protocol for early detection of vascular complication is suggested. Bisdas et al. [11] established the following protocol: (1) clinical examination of feet and legs for temperature, color, capillarity, and compartment syndrome and, additionally, continuous measurement of oxygen saturation of toe and comparison with the respective finger; (2) Doppler detection of peripheral pulses/arterial blood flow by an experienced physician every 6 h; (3) measurement of myoglobin and creatine kinase every 8 h; and (4) if items 1–3 reveal any problems, color Duplex ultrasonography is used, or in case of inconsistent results, contrast-enhanced computed tomography angiography. The same protocol is followed during the first 48 h after ECMO explantation. Therefore, distal limb perfusion is critical, and many authors recommend its implantation at the time of ECMO start or following specific criteria. Huang et al. [12] measured the mean arterial pressure of the superficial femoral artery by puncturing the vessel distal to the ECMO cannula with a 23-gauge needle. If the pressure was under 50 mmHg, a distal perfusion cannula was recommended. Similarly, a larger cannula size-to-BSA ratio could predict which patients could develop ischemia [13]. Surgical approach to solve such a problem may interest the femoral artery, the tibial artery, or the dorsalis pedis artery. If the femoral vessels are already isolated, the chimney graft anastomosed to the femoral artery could guarantee the distal perfusion of the leg. Otherwise, a cannula can be placed in the distal femoral artery or in the superficial femoral artery with the same technique described before [14–16].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree