Surgical Approaches to the Heart and Great Vessels

Primary Median Sternotomy

Median sternotomy remains the most widely used incision in cardiac surgery because it provides excellent exposure for most surgeries involving the heart and great vessels.

Technique

The skin incision normally extends from just below the suprasternal notch to the tip of the xiphoid process. A pneumatic saw with a vertical blade is most commonly used to divide the sternum. In young infants, the sternum is divided with heavy scissors. An oscillating saw is used for repeat sternotomies and some primary surgeries through limited skin incisions. Its use requires that the surgeon develop a “feel” for when the blade has penetrated the posterior table of the sternum (see Repeat Sternotomy section).

A small vein is usually evident running transversely in the suprasternal notch. At times, however, it may be large and engorged, particularly in patients with elevated right heart pressure. Excessive bleeding may occur if this vein is inadvertently injured. It is important to be aware of its presence and to coagulate it (if tiny) or to occlude it with a metal clip. If the vein has been cut and its ends have retracted, thereby making hemostasis difficult, control of bleeding can be gained by packing the suprasternal notch area and proceeding with the sternotomy. After the two sides of the sternum have been spread apart, the sites of bleeding can be easily identified and controlled.

Dissection of the suprasternal notch is not only unnecessary but can also open up tissue planes in the neck. Tracheostomy is now rarely necessary but always remains a possibility. Whenever tracheostomy is performed, a separate incision is kept as high in the neck as possible so that a superficial tracheostomy wound infection does not spread into the suprasternal notch and eventually into the mediastinum, leading to wound complications and mediastinitis.

During the division of the linea alba or the lower part of the pericardium, the peritoneal cavity may be entered. The opening should be closed immediately to prevent any spillage of blood or cold saline used for topical cooling into the peritoneal cavity, which may promote postoperative ileus.

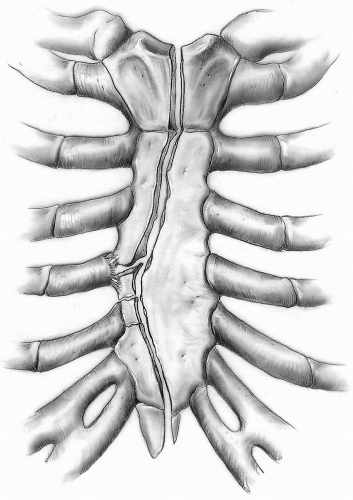

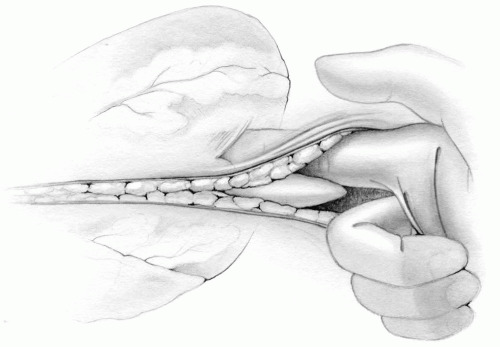

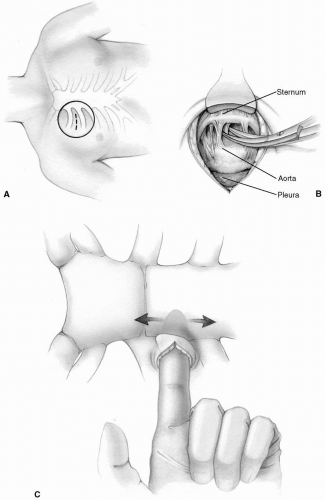

The sternotomy should be in the midline of the sternum. By dipping the thumb and index finger into the incision and spreading them against the lateral margins of the sternum into the intercostal spaces, the proper site for sternal splitting can be located and marked by an electrocautery on the periosteum. Unequal division may leave one side of the sternum too narrow and allow the closure wires to cut through the narrower segments of the bone, leading to an increased incidence of sternal dehiscence. Similarly, the costochondral junction may be damaged (Fig. 1-1).

The anesthesiologist is always asked to deflate the lungs while the surgeon is using the sternal saw so that the pleural cavities can be kept intact. This is particularly important in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hyperinflated lungs. Occasionally, however, the pleural cavities are opened by the sternal saw or during dissection of the thymus and pericardium. If the opening is small and no fluid has entered the pleural cavity, at the close of the procedure the tip of the mediastinal chest tube may be introduced for 2 to 3 cm into the pleural defect. The pleura may be opened fully, particularly in patients undergoing harvesting of internal thoracic arteries. In these cases, a separate chest tube is inserted subcostally over the lateral aspect of the diaphragm for drainage of fluid and blood and evacuation of air.

Excessive use of bone wax to control bleeding from the sternal marrow should be avoided. It can be associated with increased rates of wound infection, impaired wound healing, and, most serious of all, wax embolization to the lungs. However, the use of small amounts of bone wax is an effective tool to control bleeding from sternal edges.

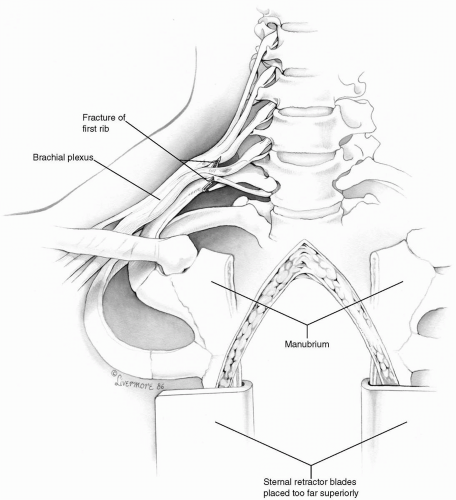

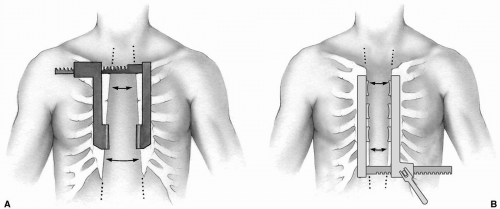

Brachial plexus injury has been associated with median sternotomy. Stretching of the plexus by hyperabduction of the arm and compression of the nerve trunks between the clavicle and first rib during sternal retraction has been implicated as a cause of injury. Introduction of a Swan-Ganz catheter through the internal jugular vein can injure the brachial plexus, either directly by the introducer itself or indirectly by the formation of a hematoma in the vicinity. The most serious cause of brachial plexus injury is fracture of the first rib (Fig. 1-2). The sternal retractor should be placed with its crossbar superiorly, so that the blades spread apart the lower third of the sternal edges. It is then opened gradually in a stepwise manner (one to two turns at a time) to prevent fractures of the first rib or sternum (Fig. 1-3A). If for some reason the crossbar of the retractor is to be placed inferiorly, it is important for the blades to be in the lower part of the incision. Many surgeons use modified sternal retractors with two or three blades on either side, placing the crossbar inferiorly. These retractors are opened just enough to provide adequate exposure (Fig 1-3B).

Retractors (e.g., Favaloro) used in harvesting the internal thoracic artery can also cause brachial plexus injury. Therefore, sudden excessive upward pull on the retractor should be avoided. The surgeon should ensure good exposure by manipulating the operating room table and his or her headlight to minimize traction of the upper sternum. Moreover, when the proximal internal thoracic artery is freed, the degree of upper sternal retraction is reduced. These simple measures can often eliminate or reduce the incidence of brachial plexus injury.

The innominate vein may be injured during dissection and division or resection of the thymus or its remnant, particularly when scarring is present from a previous surgery. The scar tissue on each side of the injured vein is dissected free. Brisk bleeding can then be controlled by simple suturing. In rare instances of severe damage to the vein, it is divided and its right end is suture ligated. The other end of the vein is left open for drainage of venous return from left internal jugular tributaries until the patient is ready to come off cardiopulmonary bypass when it is similarly suture ligated.

The innominate vein is a useful channel for an additional intravenous line, which can be used to monitor central venous pressure, particularly in infants and patients with poor peripheral veins. The catheter is introduced percutaneously into the center of a 7-0 Prolene purse-string suture buttressed with fine pericardial pledgets on the innominate vein. The purse-string suture must be tied snugly to prevent any bleeding after removal of the venous line. Sometimes a large thymic vein can be used for the same purpose.

Repeat Sternotomy

An increasing number of patients require surgical intervention a second, third, or even fourth and fifth time for replacement of prosthetic valves, definitive correction or revision of congenital heart defects, or repeat myocardial revascularization. Because it is anticipated that this trend will continue, all cardiac surgeons must acquire expertise in reoperative procedures. When making the skin incision, it is not always necessary to excise the previous scar unless it is gross and thick. The subcutaneous tissue is incised in the customary manner, and, using electrocoagulation, the sternum is marked along the midline.

Technique

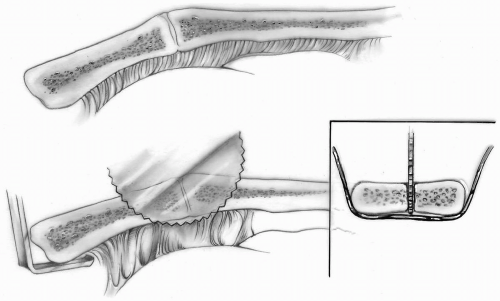

Previous wires or heavy nonabsorbable sutures are divided anteriorly but are not removed. They provide some resistance posteriorly to the oscillating saw, which helps to prevent any possible right ventricular injury (Fig. 1-4, inset). Only limited, sharp dissection adequate for the placement of a small Army-Navy retractor can be safely carried out in the suprasternal notch or around the xiphoid process.

Blunt digital dissection behind the lower sternum should rarely be practiced in patients with a previous sternotomy because of possible injury to the friable right ventricular wall (Fig. 1-5).

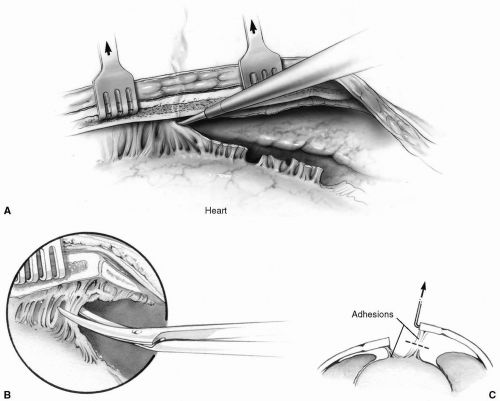

The sternum is raised by retractors at the suprasternal notch superiorly and at the xiphoid inferiorly during sternal division with an oscillating saw (Fig. 1-4). Small rake retractors are inserted into the marrow cavity on each side of the sternal edge and gently lifted upward toward the ceiling, thereby making the adhesions between the retrosternum and the heart slightly taut and accessible for division with the cautery or scissors (Fig. 1-6).

A lateral chest radiograph often reveals the proximity of the right ventricle and ascending aorta to the undersurface of the sternum. However, a computed tomography scan will accurately identify the relation between the ascending aorta and the underside of the sternum. When the ascending aorta is noted to be adherent to the undersurface of the sternum, precautions must be taken before performing a sternotomy.

Technique

Before a sternotomy is attempted, a small transverse incision is made in the second or third right intercostal space. This allows a lateral approach for dissection to free the aorta from the undersurface of the sternum. After this has been accomplished, the sternum can be divided in the manner described for repeat surgery without risk of injury to the aorta (Fig. 1-7).

Our preference is femoral artery-femoral vein bypass and core cooling to 18°C before sternotomy (see Chapter 2). Cardiopulmonary bypass is then established, and the patient is cooled to 18° to 20°C. Assisted venous drainage with a centrifugal pump or vacuum assist is useful. Aortic insufficiency owing to the presence of a bileaflet or a single-disc mechanical prosthesis or a disrupted aortic bioprosthesis may result in left ventricular distention. An

appropriately sized vent is placed into the apex of the left ventricle through a small left anterior thoracotomy as cardiopulmonary bypass is being initiated to protect the heart from overdistention (see Left Ventricular Apical Venting section in Chapter 4). Transesophageal echocardiography is always used to monitor left ventricular volume. If left ventricular distension occurs either at the initiation of bypass or when the heart begins to fibrillate, a vent is placed immediately.

appropriately sized vent is placed into the apex of the left ventricle through a small left anterior thoracotomy as cardiopulmonary bypass is being initiated to protect the heart from overdistention (see Left Ventricular Apical Venting section in Chapter 4). Transesophageal echocardiography is always used to monitor left ventricular volume. If left ventricular distension occurs either at the initiation of bypass or when the heart begins to fibrillate, a vent is placed immediately.

If the sternotomy is uneventful, the patient is gradually rewarmed and the surgery is completed in the usual manner. Conversely, if the aorta is torn or disrupted, hypothermic arrest is instituted and the ascending aorta is repaired or replaced. The intended surgery is then resumed to its completion.

This precaution may appear to be a very major undertaking with its own possible serious complications. However, it is the only way to prevent catastrophic hemorrhage with a frequently fatal outcome.

This precaution may appear to be a very major undertaking with its own possible serious complications. However, it is the only way to prevent catastrophic hemorrhage with a frequently fatal outcome.When the possibility of aortic injury is not anticipated and the aorta is entered during sternotomy, towel clamps are used to reapproximate the sternal edges in an effort to tamponade the bleeding site. Direct pressure should be applied by an assistant surgeon while cardiopulmonary bypass is established expeditiously through the femoral artery and vein, as noted in the preceding text.

The division of the posterior table of the sternum may be accomplished with heavy scissors under direct vision. This is facilitated by elevating the sternum slightly with a rake retractor. Such a maneuver is particularly important at the manubriosternal junction, where the manubrium takes a posterosuperior course (Fig. 1-4).

Fibrous adhesions to the undersurface of the sternum are mainly along the previous sternotomy. After dividing these fibrous adhesions with an electrocautery or scissors, the sternum is relatively free (Fig. 1-6). An adequate dissection is carried out so that the sternal retractor can be safely positioned and slowly opened.

By slow and careful sharp dissection along the right inferior border of the heart, the proper plane can be

identified relatively easily. Some surgeons find that the use of the electrocautery blade on a low setting allows this dissection to be accomplished with less bleeding from the pericardial surfaces. The dissection can then be gradually carried upward, exposing the right atrium and aorta for cannulation in preparation for cardiopulmonary bypass.

identified relatively easily. Some surgeons find that the use of the electrocautery blade on a low setting allows this dissection to be accomplished with less bleeding from the pericardial surfaces. The dissection can then be gradually carried upward, exposing the right atrium and aorta for cannulation in preparation for cardiopulmonary bypass.

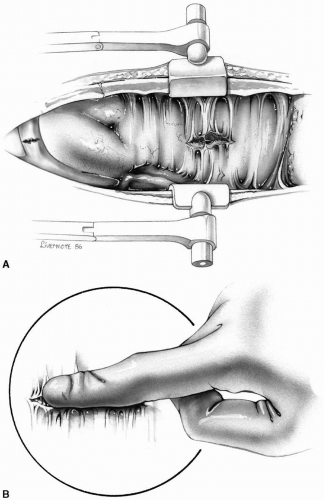

A small (Himmelstein) chest retractor can now be inserted and must be spread apart only slightly; an overzealous attempt to widen the sternal opening results in stretching of the right ventricular wall. Tearing of the right ventricle because of saw injury or overstretching of the sternotomy is a life-threatening

complication. The bleeding should be controlled by direct pressure on the site while cardiopulmonary bypass is initiated as promptly as possible. With the right ventricle totally decompressed, the wound is repaired with multiple, fine pledgeted sutures (Fig. 1-8). In cases of saw injury, pressing the two sternal halves together and toward the heart may tamponade the bleeding while cannulation of the femoral vessels is accomplished.

complication. The bleeding should be controlled by direct pressure on the site while cardiopulmonary bypass is initiated as promptly as possible. With the right ventricle totally decompressed, the wound is repaired with multiple, fine pledgeted sutures (Fig. 1-8). In cases of saw injury, pressing the two sternal halves together and toward the heart may tamponade the bleeding while cannulation of the femoral vessels is accomplished.

In patients undergoing repeat sternotomies, the innominate vein is often adherent to the undersurface of the manubrium. It may be injured directly with the saw or torn as the sternal halves are being retracted (Fig. 1-8). In most cases, the bleeding can be controlled with digital pressure on the opening in the vein while the vein is carefully dissected free from the posterior aspect of both sides of the manubrium. If control of the bleeding cannot be rapidly secured, the two sternal halves should be pushed together with slight downward pressure by the assistant surgeon to minimize blood loss. Blood should be transfused as necessary and femoral arterial and venous cannulation obtained as quickly as possible. The innominate vein can then be dissected free and repaired with 5-0 Prolene suture on cardiopulmonary bypass.

If the innominate vein injury is a complex tear or transection, repair may not be feasible. Then the right side of the vein may be oversewn immediately, but the left side should be allowed to bleed freely and the blood returned to the bypass circuit by a pump sucker during cardiopulmonary bypass.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree