Surgery of the Mitral Valve

Rheumatic fever continues to be the major cause of acquired valve disease worldwide. Rheumatic fever results in a pancarditis, but the pathologic effects are noted predominantly on the endocardium and cardiac valves, particularly the mitral valve. During the acute phase of myocarditis, the left ventricle dilates, which causes stretching of the annulus of the mitral valve. The mitral insufficiency thus produced is temporary and disappears when the left ventricle regains its normal function. Rheumatic heart disease is a chronic and progressive condition. The earliest permanent change is the fusion of the commissures, followed by thickening and fibrosis of the valve leaflets. These pathologic events are responsible for the creation of the turbulent flow that, together with the continuing rheumatic process, further enhances the progression of the disease and eventual involvement of the subvalvular apparatus. The chords and papillary muscles become thickened, shortened, and fused to each other and to the mitral leaflets. A continuous cycle of progression of pathologic changes and increasingly disturbed flow is therefore created, eventually leading to severe mitral valve disease, notably mitral stenosis or mixed stenosis and insufficiency with or without calcification.

Degenerative and myxomatous changes are the most common cause of mitral valve disease in North America and Western Europe today. These changes affect the leaflets and subvalvular apparatus leading to mitral regurgitation. As the population ages, surgeons are seeing more patients with mitral insufficiency secondary to calcific mitral valve disease.

Functional mitral regurgitation may be caused by ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathies. The leaflets and subvavular structures are normal but leaflet coaptation is prevented by annular dilation, left ventricular wall motion abnormalities or generalized cavity dilation, and/or papillary muscle dysfunction. Ischemic heart disease and myocardial infarction may also lead to ischemic mitral valve prolapse due to papillary muscle or chordal injury.

Bacterial endocarditis can affect both normal and abnormal heart valve leaflets. The infection may burrow through and invade the mitral valve annulus. Infrequently the endocarditis extends to the aortic valve and/or the subvalvular apparatus of the mitral valve. It can destroy the mitral valve leaflet configuration, resulting in gross mitral valve insufficiency.

Surgical Anatomy of the Mitral Valve

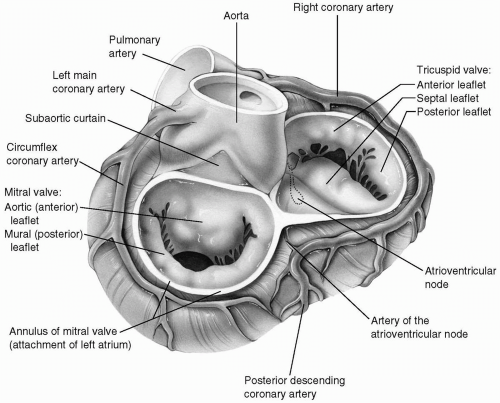

The mitral valve forms the inlet of the left ventricle. It consists of two leaflets: the anterior (aortic) and posterior (mural) leaflets, which are attached directly to the mitral annulus and to the papillary muscles by primary and secondary chordae tendineae. A series of chordae tendineae originates from the fibrous tips of the papillary muscles and inserts into the free edges and the undersurfaces of the mitral leaflets, thereby preventing the prolapse of the leaflets into the left atrium during systole and contributing to the competency of the mitral valve. The attachments of the leaflets to the annulus meet at the anterolateral and posteromedial commissures. One-third of the mitral valve annulus provides attachment for the anterior leaflet, and the posterior leaflet arises from the remaining two-thirds of the annulus. Although from the strict anatomic point of view the mitral valve consists of two leaflets, there are multiple slits within the posterior leaflet. These slits give rise to scallops of leaflet that may prolapse and give rise to valvular insufficiency. Most surgeons and echocardiographers have adopted the classification of Carpentier, which divides both the anterior and posterior leaflets into three functional segments (Fig. 6-1).

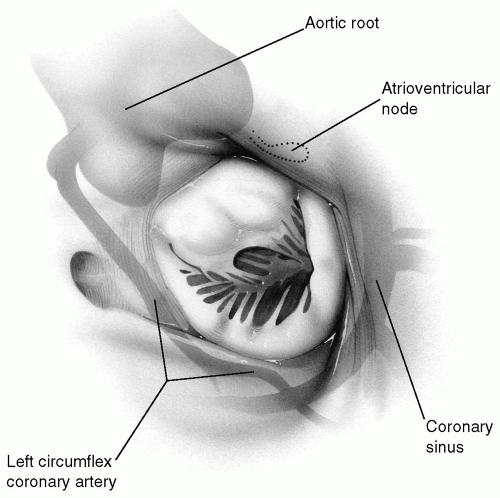

When the posterior annulus is studied from a strictly anatomic standpoint, it is attached to the left ventricular myocardium through the interposition of a narrow membrane and is therefore actually slightly elevated above the opening of the left ventricle. This subannular membrane extends underneath the posterior annulus to the region of both commissures and merges with the fibrous skeleton of the heart. The anterior leaflet is continuous with the adjoining halves of the left and noncoronary annuli of the aortic valve and also with the fibrous subaortic curtain located beneath the commissure between the left and noncoronary aortic sinuses (Fig. 6-2).

The annulus of the mitral valve is surrounded by many important and vital structures. The nearby left circumflex coronary artery traverses around the mitral annulus in the posterior atrioventricular groove. The coronary sinus also runs in the more medial segment of the same groove. The atrioventricular node and its artery, usually a branch of the right coronary artery, run a course parallel and close to the annulus of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve near the posteromedial commissure. As mentioned earlier, the remainder of the anterior leaflet annulus is contiguous with the aortic valve. These relationships have significant clinical implications during mitral valve surgery (Fig. 6-3).

Functional mitral regurgitation occurs secondary to annular or left ventricular changes with anatomically normal leaflets and subvalvular structures. One etiology is simple annular dilation due to left ventricular enlargement. In this case the leaflet motion is normal, but the leaflets are pulled apart preventing normal coaptation. Localized left ventricular wall motion abnormalities result in displacement of the papillary muscles. This results in apical tethering of the leaflets with restricted mitral leaflet motion in systole. In some patients, both mechanisms contribute to functional mitral regurgitation.

Technical Considerations

Incision

A median sternotomy is the incision most commonly used. Standard aortic and bicaval cannulation is performed. A left or right thoracotomy also affords good access to the mitral valve. Recently, port access combined with a small right thoracotomy has been used for mitral valve procedures.

Myocardial Preservation

When satisfactory cardiopulmonary bypass has been established, the aorta is cross-clamped and cold blood cardioplegic solution is administered into the aortic root to bring about prompt diastolic cardiac arrest. Further administration of blood cardioplegic solution is often administered by the retrograde method (see Chapter 3).

Satisfactory administration of cardioplegic solution into the aortic root can only be accomplished if the aortic valve is competent. Aortic insufficiency, if present, directs the cardioplegic solution into the left ventricular cavity causing distension and stretch injury to the myocardium. This can be prevented by administering cardioplegic solution using the retrograde technique alone (see Chapter 3).

Exposure of the Mitral Valve

There are many different approaches for entering the left atrium to provide good exposure of the mitral valve.

Interatrial Groove Approach

The left atrium is opened with an incision just posterior to the interatrial groove (Fig. 6-4). The opening can be extended inferiorly onto the posterior wall of the left atrium.

There is always a variable amount of loose fatty tissue in the interatrial groove. Fragments of fat and loose tissue may enter the left atrial cavity during the atriotomy. Similarly, when the atriotomy is being closed, fatty fragments may invaginate through the closure into the left atrium.

Upward extension of the incision behind the superior vena cava should be avoided because subsequent closure may be difficult. Generous inferior extension to the back of the heart provides satisfactory exposure of the mitral valve in most cases (Fig. 6-5). Closure of this posterior extension of the incision is facilitated by suturing from inside the left atrial cavity under direct vision.

At least one of the caval snares must be loosened during administration of cardioplegic solution to allow the venous return from the coronary sinus to drain into the oxygenator. If both snares are down, cardioplegia may distend the right heart. If the right atrium is not opened at any time, the cavae do not necessarily require snares around them because venous drainage may be adequate.

The aorta must be cross-clamped before opening the left atrium to avoid systemic air embolism.

Specially designed retractors are introduced into the left atrium. Optimal exposure is obtained when the retractor held by the assistant pulls the atrial wall at least 1 cm from the mitral annulus upward and slightly to the patient’s left. Many self-retaining retractors are available to improve exposure of the mitral valve. They may be particularly helpful if there is a shortage of assistants in the operating room.

Because the atrial wall may be somewhat friable, excessive pull on the retractor may produce a shearing tear of the atrial wall edges, thereby complicating closure. On many occasions, two smaller retractors provide better and safer exposure than a single large one because the assistant is able to divert the pulling force from one retractor to the other to accommodate the surgeon’s view (Fig. 6-6).

Transatrial Oblique Approach

If the left atrium is small, exposure of the mitral valve through the interatrial groove may be suboptimal. In reoperative procedures, dense adhesions may make dissection hazardous, particularly near the region of the interatrial groove. In such cases, an oblique transatrial approach provides excellent exposure of the mitral valve (Fig. 6-7). The aorta is cross-clamped, and cardioplegic solution is administered as before. After the aorta is clamped, an oblique incision is made on the right superior pulmonary vein with a long-handled no. 15 blade. Warm blood will gush out to decompress the left atrium. This will allow expeditious cooling and arrest of the heart.

The vena caval snares are secured. The opening in the right superior pulmonary vein is extended obliquely across the right atrial wall. By gently retracting the right atrial wall edges, the incision can now be extended across the interatrial septum and through the fossa ovalis just inferior to the limbus (Fig. 6-7B). At this time, a retrograde cardioplegic cannula can be introduced into the coronary sinus under direct vision. It can be secured with a fine purse-string suture of Prolene placed on the inside of the coronary sinus ostium, away from the conduction tissues (see Chapter 3). In this manner, retrograde infusion of cardioplegic solution can supplement the antegrade technique.

Extension of the septal incision far beyond the anterior limbus of the fossa ovalis may divide the mitral valve annulus, making mitral valve replacement insecure. It could also create a passage outside the atrium into the transverse sinus. The septal incision should therefore terminate just distal to the anterior margin of the fossa ovalis. The septal incision can be extended inferiorly on the fossa ovalis if additional exposure is required (Fig. 6-7C).

The septal edges are retracted with two small retractors. This provides excellent exposure of the mitral valve without distorting it, an important advantage when mitral valve reconstruction is being contemplated (Fig. 6-8).

Transatrial Longitudinal Septal Approach

When there are excessive adhesions from previous surgery, excellent exposure of the mitral valve can be obtained through a longitudinal septal approach. Depending on the size of the right atrium, an oblique or longitudinal incision is made on the right atrial wall. Excellent exposure of the right atrial cavity and interatrial septum is thus obtained. A longitudinal incision is made along the posterior margin of the fossa ovalis and extended both superiorly and inferiorly to provide good exposure of the mitral valve (Fig. 6-9).

The annulus of the mitral valve is at the muscular septal wall most anterior to the fossa ovalis. Therefore, the longitudinal septal incision should be made posterior to the fossa ovalis, leaving a good margin of septal wall between the opening and the mitral annulus. This segment of the septum is retracted to provide excellent exposure of the mitral valve.

Open Mitral Commissurotomy for Mitral Stenosis

Mitral stenosis secondary to longstanding rheumatic fever has continued to be the dominant mitral valve disease affecting large populations worldwide. The disease is now being seen with increasing frequency among immigrants coming to the United States and Western Europe, where rheumatic heart disease had become uncommon.

Mitral commissurotomy can be accomplished safely and precisely under direct vision. With the availability of cardiopulmonary bypass, the closed technique is rarely used today except in third world countries.

A median sternotomy is the incision of choice, although the mitral valve can be approached through either a right or left thoracotomy.

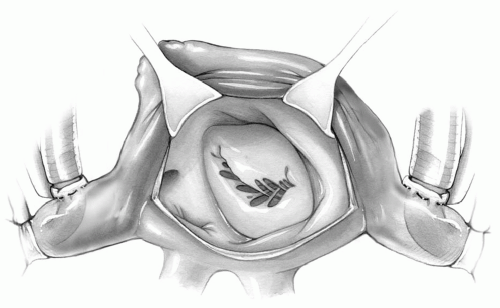

The left atrium is incised by one of the techniques described in the preceding text to expose the mitral valve. The mitral leaflets are identified and, by means of two fine Prolene traction sutures, gently pulled upward toward the left atrial cavity. At times, use of nerve hooks can also provide the same effect. Often this maneuver will stretch the valve leaflets apart and show the line of commissural fusion as a furrow extending between them. If visibility through the valve ostium is adequate, the chords and papillary muscles are examined for evidence of shortening and fusion to each other and, especially, fusion to the undersurfaces of the valvular leaflets.

A right-angled clamp is introduced through the mitral valve opening and placed directly below the fused commissures. It is then opened gently beneath the leaflets to facilitate incision with a no. 15 blade onto the commissures without severing the chordal attachments (Fig. 6-10). Occasionally, the papillary muscles are fused to the undersurface of the leaflet, making commissurotomy hazardous. With the opened right-angled clamp in place, the commissure is first incised near the annulus; this incision is extended inward over the clamp, cutting vertically into the papillary muscle and the thickened, fused chords for a short distance.

Care must be taken to divide the head of the papillary muscle fused to the undersurface of mitral leaflets straight along its long axis. Oblique division may weaken or even result in a partial division of the papillary muscle necessitating its repair or reimplantation or even requiring mitral valve replacement.

The extent of commissurotomy must be as complete as possible without producing valvular incompetence. If the incision is extended too far toward the annulus, annuloplasty may become necessary (see Mitral Valve Reconstruction section).

Closed Mitral Commissurotomy

Closed mitral commissurotomy is now rarely performed in most Western countries. Consequently, only a few of the current generation of cardiac surgeons have had adequate experience with this technique. Nevertheless, closed mitral valvotomy remains a good operation in selected subgroups of patients, and the long-term results have been consistently satisfactory. In third world countries, closed valvotomy continues to be the preferred form of therapy because of its simplicity and low cost compared with open-heart procedures.

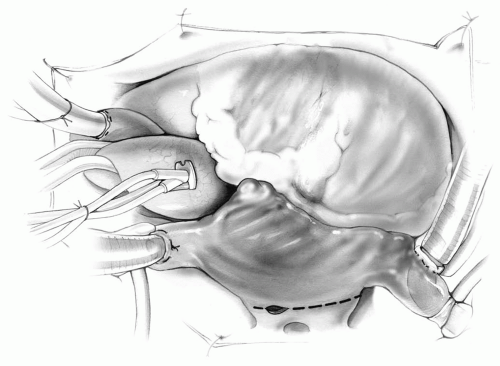

Technique

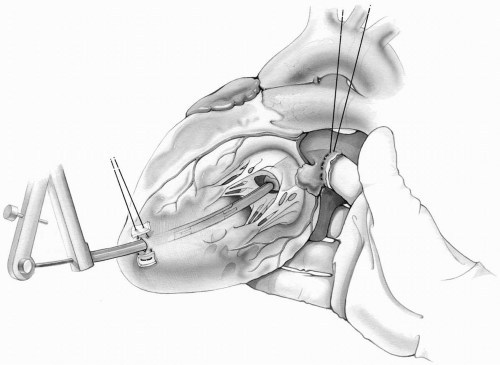

A left posterolateral or anterolateral thoracotomy is made through the bed of the fifth rib. The lung is retracted posteroinferiorly, and a long incision is made anterior and parallel to the left phrenic nerve. The pericardium is then suspended with traction sutures. The left atrial appendage is identified and excluded with a side-biting clamp. A purse-string suture of 2-0 Prolene is placed around the left appendage. Another purse-string suture, reinforced with pledgets, is then placed into the apex of the left ventricle. The left atrial appendage is incised within the purse-string suture, and the surgeon’s right index finger is introduced into the left atrium. The mitral valve is palpated to detect

calcification, the degree of mitral stenosis, or the presence of insufficiency (Fig. 6-11).

calcification, the degree of mitral stenosis, or the presence of insufficiency (Fig. 6-11).

The index finger should be introduced gently, without undue pressure. If the atrial appendage tears, it will result in brisk bleeding.

Preoperative echocardiography is always performed to study the mitral valve pathology and to detect the presence of a blood clot in the left atrial appendage. Nevertheless, before applying clamps to the appendage or introducing a finger into the atrial cavity, the left atrial appendage should be palpated carefully to detect a blood clot. If thrombus is suspected, it should be excluded by clamping the base of the appendage and then removed. If this is not possible, the closed procedure should be abandoned, and the operation converted to an open valvotomy with the use of extracorporeal circulation.

The index finger should not occlude the mitral orifice for more than two or three cardiac cycles to avoid precipitating dysrhythmia and possible cardiac arrest.

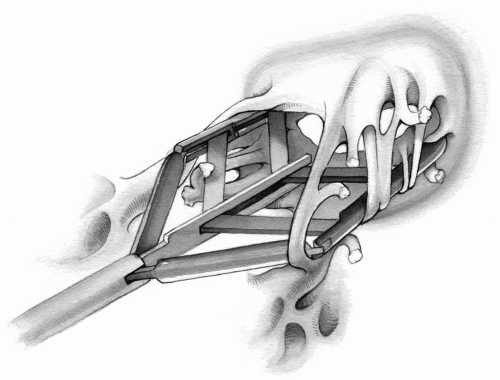

When the right index finger is in the left atrium, the heart is elevated with the remaining three fingers and palm of the right hand to bring the left ventricular apex into view. With a no. 11 blade held in the left hand, the surgeon makes a small ventriculotomy within the previously placed apical purse-string suture. This can also be performed by the surgeon’s assistant if desired. This opening is now enlarged with a series of Hegar dilators until it accommodates the diameter of the Tubb valvulotome. The Tubb dilator is then introduced into the left ventricle with the surgeon’s left hand and advanced through the mitral valve into the left atrium. It is then opened quickly to the preset limiting extent of 3.5 to 4.5 cm, closed, and removed. The surgeon’s finger is then removed, and the purse-string suture on the left ventricular apex is snugged down and tied over pledgets.

It is most important not to open the dilator until the surgeon can feel its tip with the right index finger in the left atrial cavity. Premature opening of the dilator may injure or tear the subvalvular structures and result in mitral insufficiency (Fig. 6-12).

After completion of the dilation, the dilator must be closed completely before removal. Inadequate closure of the dilator will cause tearing of the left ventricular opening during withdrawal.

Adequacy of the valvotomy and any evidence of a mitral insufficiency jet must be ascertained with the surgeon’s index finger while it is still in the left atrium.

Every precaution should be taken to prevent air from entering the left atrium or left ventricle during the procedure.

Conversion of a Closed Mitral Valvotomy to the Open Technique

In young adults, the mitral lesion may be fibrotic but elastic and without calcification. The surgeon may find it possible to stretch the orifice maximally with a Tubb dilator only to note that the orifice resumes its previous stenotic size on removal of the dilator. Such patients must be treated with open mitral commissurotomy.

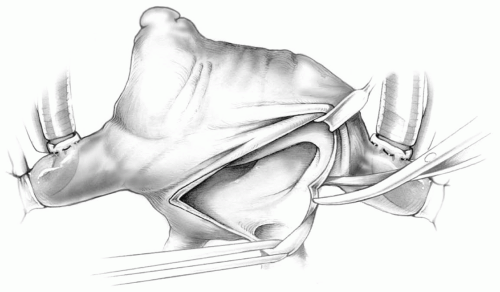

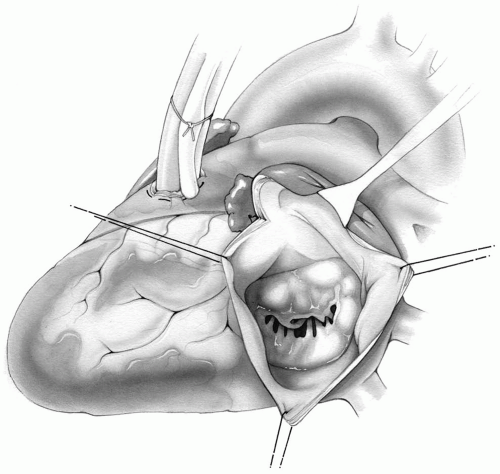

It is always a prudent precaution to perform this procedure with a heart-lung machine available on standby so that the surgeon will have the option of using cardiopulmonary bypass if it becomes necessary. Venous drainage can be accomplished through a cannula placed in the main pulmonary artery. Arterial return may be through a cannula either in the descending aorta or femoral artery. A left atriotomy will give excellent exposure of the mitral valve (Fig. 6-13).

Mitral Valve Reconstruction

The mitral apparatus includes the leaflets, annulus, chordae tendinae, papillary muscles, and the left ventricle. Mitral valve incompetence can be the result of annular dilation, chordal elongation or rupture, leaflet abnormalities, papillary muscle injury or displacement, and/or alterations of left ventricular size, shape, or wall motion. For this reason, it is necessary to examine and evaluate every aspect of the mitral valve complex in detail so that efforts at valvular reconstruction will be fruitful. The shape and size of the annulus is noted. Nerve hooks or forceps are used to determine the pliability and motion of the leaflets. The leaflet motion is classified as normal (type I), prolapsed (type II), or restricted (type III). The chords and papillary muscles are then assessed.

FIG 6-13. Left atriotomy for exposure of the mitral valve if cardiopulmonary bypass becomes necessary. |

All techniques described previously for approaching the mitral valve provide excellent exposure. The transseptal approach, however, has the added advantage of allowing the valve to be evaluated in its normal anatomic configuration without being distorted by excessive retraction. This is a point of importance when contemplating reconstructive procedures (Fig. 6-8).

Mitral Valve Annuloplasty

Commissuroplasty

In a subgroup of patients, the cause of mitral insufficiency is annular dilation only; therefore, reducing the enlarged annulus is all that is required. This can be accomplished by successive figure-of-eight sutures at both commissures, incorporating only the posterior annulus.

The needle of an atraumatic 2-0 Tevdek suture is passed through the annulus at the commissure and then again 1 cm further along on the posterior annulus. The same suture is then placed through the annulus 0.5 cm from the commissure (or midway between the first two stitches). Finally, it is passed through the annulus 1 cm further away before it is tightened and securely tied. If indicated, another figure-of-eight suture, similarly placed, can decrease the annular size even more (Fig. 6-14). Good

judgment dictates the appropriate size of each stitch so that a good repair can be accomplished without overcorrection. These sutures may be buttressed with Teflon felt pledgets for added security.

judgment dictates the appropriate size of each stitch so that a good repair can be accomplished without overcorrection. These sutures may be buttressed with Teflon felt pledgets for added security.

It is important to have an anatomically symmetric annulus. Therefore, the procedure should include both the anterolateral and posteromedial commissural aspects of the annulus in exactly the same manner.

Inadequate reduction of the annulus may not correct the valvular insufficiency. The mitral valve must be evaluated after annuloplasty for incompetence by injecting saline into the left ventricle and looking for an insufficient jet.

Overcorrection will result in mitral stenosis. The orifice may be examined digitally, or an appropriately sized obturator may be introduced into the valve to ascertain the presence of an adequately sized orifice.

When the pathologic entity is degenerative disease, the tissues are thin and weak, and sutures may tear through. The use of Teflon felt or pericardial pledgets may help prevent this complication.

Annuloplasty should incorporate only the posterior annulus and not the anterior annulus because it is usually the posterior portion that is dilated. Incorporation of the anterior segment of the annulus may distort the mitral configuration and thereby result in valvular insufficiency.

The sutures should be placed in the fibrous annulus, rather than into the leaflet itself, or into the atrial wall beyond the annulus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree