SPLENECTOMY WITH PROXIMAL SPLENIC ARTERY LIGATION AND ESOPHAGOGASTRIC DEVASCULARIZATION

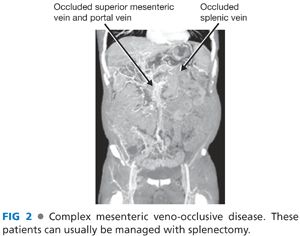

■ The indications for this procedure include patients with a life-threatening complication from portal hypertension and complex mesenteric veno-occlusive disease or poor venous drainage of the spleen (left-sided portal hypertensive physiology) (FIG 2).

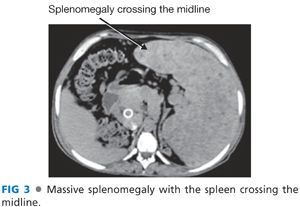

■ Patients with long-standing thrombocytopenia (platelets <35,000/μL) and massive splenomegaly needs a splenectomy. The spleen is fibrotic and will remain large (and platelet counts will remain low) following shunt surgery alone. Also, a massive spleen will make many portal hypertension surgical procedures impossible and, as a result, splenectomy is the first portion of the procedure (FIG 3).

■ The procedure can be done with a laparoscope. If there is significant portal hypertension and collaterals, preoperative splenic embolization should be done immediately prior to the procedure. If done more than a few hours before the splenectomy, the patient will have significant adverse symptoms and the spleen will become soft and easy to injure during surgery. The size of the spleen and the severity of the portal hypertension usually favor an open procedure.

■ Key steps include the following:

■ Exposure above the spleen with generous retraction of the abdominal wall superiorly

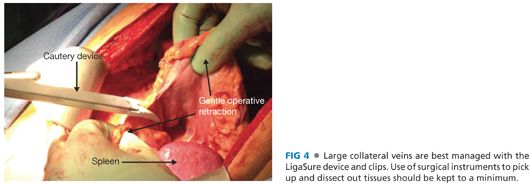

■ Keep dissection to a minimum. Use hands instead of metal retractors for operative exposure. Collateral veins are best ligated using a “no-touch” technique and either surgical clips or an electrosurgical device (such as a LigaSure or Harmonic scalpel) (FIG 4).

■ Divide enough short gastric vessels to expose the splenic vein.

■ Ligate the splenic artery with surgical clips. Identify the splenic artery proximally, but more importantly, in a location that is easy to dissect. Do not circumferentially dissect the splenic artery; the splenic vein and branches are posterior to the artery and injury to these veins can be extremely difficult to manage. Ligation of the artery will decompress the spleen, lower portal pressures, and profoundly reduce bleeding.

■ Mobilize the spleen by taking down collaterals to the retroperitoneum with the LigaSure device and clips.

■ Use the argon beam coagulator to mobilize the planes around the spleen. This effectively manages the innumerable small collaterals.

■ Leave the short gastric vessels at the upper pole of the spleen to the end of the procedure after the hilum has been divided.

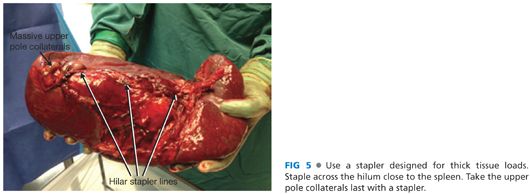

■ Achieve circumferential control of the splenic hilum as close to the spleen as possible. Advance a surgical stapler across the hilum. Make sure the stapler is designed to traverse thick tissue loads. Fire the stapler after assuring no pancreas tissue will be transected with the stapler.

■ Once the hilum is transected, divide the remaining short gastric veins either with the stapler or surgical clips (FIG 5).

■ Place clips on the splenic artery close to the celiac artery. Once again, circumferential dissection of the artery should not be done.

■ Complete the esophagogastric devascularization. Identify any collateral vessels behind the stomach and in the gastrohepatic ligament. Ligate these veins with clips (FIG 6).

■ Repeat portal pressure measurements to determine whether a shunt is needed. Cannulate collateral veins prior to ligation. Direct pressure measurements of the splenic vein may be necessary. Multiple measurements may be needed.

■ A shunt should be done if there is a viable target for mesenteric venous inflow and central venous outflow and a postsplenectomy mesenteric-systemic gradient of 12 mmHg.

PROXIMAL SPLENORENAL SHUNT

■ This procedure is indicated for persistent portal hypertension following splenectomy and functions as a nonselective shunt. The confluence of the superior mesenteric vein and splenic vein should be patent with a patent splenic vein. A pressure gradient between the splenic vein and central venous system of 12 is needed to maintain shunt patency. If pressure monitoring during the case seems unreliable, a small, easy to repair venotomy in the splenic vein to gauge the pressure in the splenic vein will inform the decision on whether a proximal splenorenal shunt is needed following splenectomy.

■ Generous mobilization of the splenic vein is needed to this procedure. This is not always technically possible and alternative approaches include minimal dissection of the splenic vein and use of a vein conduit or an alternative shunt procedure.

■ Key steps to the procedure

■ Find the left renal vein. The location of the renal vein anterior to the aorta should be confirmed on preoperative imaging.

■ Mobilize the splenic flexure of the colon to expose the left kidney. The collaterals in this are best managed with the argon beam photocoagulator.

■ Enter Gerota’s fascia. This plane is less vascular than the plane anterior to the kidney and posterior to the colon mesentery. Dissect toward the renal hilum until the vein is identified.

■ In some patients, the renal vein can be dissected freely, directly through the colon mesentery (without mobilization of the colon).

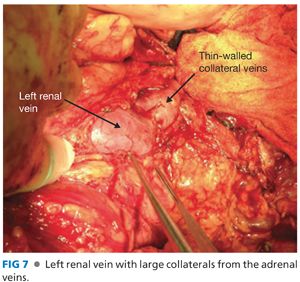

■ The left renal vein may have numerous large collateral veins (FIG 7). Dissect a sufficient amount of the vein to place a vascular clamp. Only divide these collateral veins if necessary; they are extremely thin walled and difficult to manage.

■ Mobilize the splenic vein and pancreas. Only dissect as much as needed to create an anastomosis between the renal vein and the splenic vein. The dissection is difficult and is best managed with a needle tip electrocautery, small surgical clips, and meticulous gentle dissection. Bleeding from the splenic vein or other veins in this area is best repaired with Prolene suture and pledgets.

■ Administer systemic heparin. Skip this step if there is ongoing bleeding. Much of this bleeding will stop once the shunt is created.

■ Place a clamp on the left renal vein, usually in the anterior and superior location.

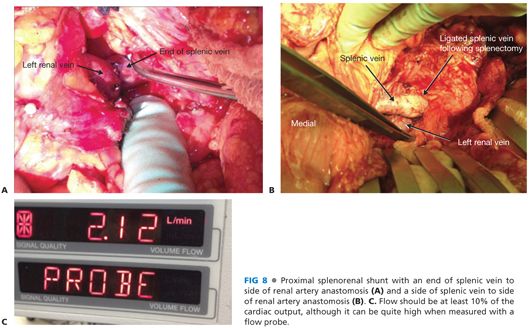

■ Depending on how the vessels line up, the anastomosis to the splenic vein can occur to the end of the vein (FIG 8A) or, more commonly, to the side of the splenic vein (FIG 8B). Clamp placement on the splenic vein is among the most challenging aspects of the case. It is critical that an easy, tension-free anastomosis is possible. If this is not possible, a vein graft conduit (such as the saphenous vein) should be considered.

■ Complete the back wall of the anastomosis and tie with a small air knot to permit growth. Prolene suture is used in adults and polydioxanone (PDS) suture in children. Check shunt inflow from the splenic vein. Clot can form within the vein following splenectomy; if this occurs, perform a thrombectomy. Complete the front wall of the anastomosis, leaving a small growth knot.

■ Remove the renal vein clamp first and assess for bleeding. Remove the splenic vein clamp.

■ Check flow with a Doppler and flow probe. Flow is usually about 10% of the estimated cardiac output, although it can be quite high (FIG 8C).

■ Flow can be augmented by further ligation of collateral veins and/or a reduction in the CVPs. Collateral veins around the stomach and esophagus should be ligated in all cases.

■ Leave a drain near the area of the splenic vein dissection. Recheck mesenteric venous pressures.

INFERIOR MESENTERIC VEIN TO LEFT RENAL VEIN SHUNT

■ The inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) is too small to provide adequate inflow for a shunt in most patients. In some patients with complex mesenteric veno-occlusive disease, the IMV can be large and spared of chronic occlusive disease. These patients should have a splenectomy. If there is significant mesenteric venous pressure following splenectomy and there are not better inflow vessels available, the IMV to left renal vein shunt is a good option.

■ Key steps to the procedure

■ Assure the IMV is large (about 50% the diameter of the left renal vein) and has sufficient pressure to maintain shunt patency. Check pressure in the IMV, making sure not to injure any areas of the vein that might affect flow through the shunt.

■ Mobilize the left renal vein directly through the colon mesentery, if possible. If not, expose the left renal vein as described in the earlier section describing the proximal splenorenal shunt.

■ The left renal vein may have numerous large collateral veins (FIG 7). Dissect a sufficient amount of the vein to place a vascular clamp. Only divide these collateral veins if necessary; they are extremely thin walled and difficult to manage.

■ Mark the course of the IMV to assure proper orientation upon creation of the shunt.

■ Administer systemic heparin.

■ Place a clamp in the proper location on the left renal vein to facilitate a properly aligned and easy to sew anastomosis.

■ Ligate and divide the IMV. Check inflow and do a thrombectomy, if necessary. Place a clamp as close to the pancreas as possible maintaining proper vein alignment.

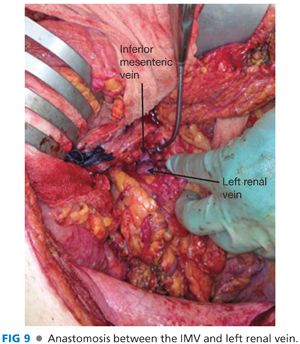

■ Create an anastomosis between the IMV and left renal vein (FIG 9). Prolene suture is used in adults and PDS suture in children. Complete the back wall and once again check inflow. Flush with heparinized saline. Leave a small growth knot to allow the anastomosis to expand.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree