Superior Vena Cava Syndrome: Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Treatment

P. Michael McFadden

The superior vena cava and its important intrathoracic venous tributaries are located in a tight compartment within the superior mediastinum, immediately adjacent and anterior to the trachea and right main bronchus. Lymph nodes that drain the entire right chest and lower portion of the left chest surround the superior vena cava and its adjacent structures. Significant extrinsic pressure, encasement, thrombosis, or actual invasion of the superior vena cava, causing an obstruction of the venous return from the head, neck, and upper extremities, may lead to unmistakable signs and symptoms. Characteristics of this type of obstruction are called the superior vena cava syndrome, first described by Hunter52 and later by Stokes.90

Clinical Manifestations

The superior vena cava syndrome constitutes a constellation of signs and symptoms resulting from either extrinsic or intrinsic obstruction of the superior vena cava and causing congestion of venous outflow from the head, neck, and upper extremities. A resulting increase in venous pressure leads to dramatic signs and symptoms. According to Wilson100 and Weinberg,97 important factors that determine the nature of the clinical presentation include the rate with which the obstruction progresses, its completeness, and the location of the superior vena cava obstruction relative to the azygos vein. The most common presenting symptoms, best described by Yellin and associates,104 include swelling of the face, neck, arms, and upper chest, often accompanied by venous distention. The eyes are often affected first. The patient may complain of tearing, proptosis, and conjunctival edema.84 Retinoscopy may reveal edema and venous engorgement, as reported by Leys and associates.63 The face may appear cyanotic or have a rubescent flush, as described by Parish,78 Armstrong,8 and Chen19 (Fig. 177-1). Dilated venous channels often appear over the anterior chest wall. These signs and symptoms are greatly exaggerated when the azygos vein is also obstructed. Headache, dizziness, tinnitus, and a “bursting” sensation in the head on bending forward all follow in short succession. Venous hypertension can lead to the dire consequences of jugular venous and cerebrovascular thrombosis. Blindness may result from retinal venous thrombosis.

Since most cases of superior vena cava obstruction are caused by carcinoma of the lung, structures contiguous with the superior vena cava may also be involved. Respiratory complaints are the second most common presenting symptoms.104 Symptoms ranging from a mild irritating cough to dyspnea and, with severe airway obstruction, even respiratory arrest may result from compression of the trachea or right main bronchus. The phrenic, vagus, and sympathetic nerves lie within the superior mediastinum; involvement of these structures can lead to paralysis of the right hemidiaphragm, hoarseness, pain, or Horner’s syndrome. The superior vena cava syndrome in children, unlike that in adults, often constitutes a medical emergency. Severe airway compromise is common owing to the tight thoracic compartment and markedly pliable tracheobronchial tree, as reported by Neuman73 and Issa.53

Etiology

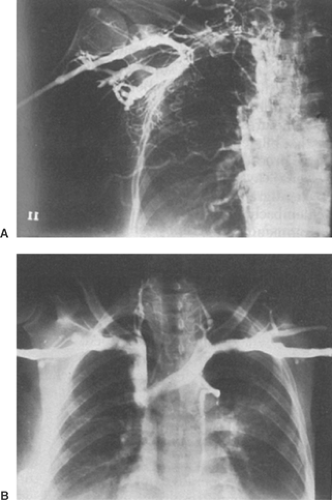

During the first half of the twentieth century, most reported cases of superior vena cava syndrome were the result of nonmalignant mediastinal disease. Syphilitic aneurysms accounted for nearly half of the reported cases. Successful treatment and prevention of this disease has now made syphilitic aneurysms and their sequelae a rarity. The author and others—Banker,13 Lochridge,65 Ahmann,3 Helms,51 and Yellin104—previously reported that malignancy accounted for more than 90% of all superior vena cava obstructions. These earlier studies indicated that 80% to 97% of cases of superior vena cava syndrome resulted from vena cava obstruction by mediastinal malignancy (Fig. 177-2). The rise in lung cancer was the most common cause of superior vena cava syndrome in the latter half of the twentieth century, paralleling the increased tobacco use following World War II. Most such carcinomas are of bronchial origin. Malignancy now remains the leading cause of superior vena cava syndrome. However, Rice and associates82 have found that malignancy now accounts for only 60% of the cases because of a

sharp rise in the use of intravascular devices related to benign obstructions. The superior vena cava syndrome occurs in approximately 3% to 15% of lung cancer patients, and— according to Weinberg,97 Urban,94 Elias,34 Rice,82 and Wilson100—small-cell lung cancer is the most frequent cell type associated with this syndrome. Lymphoma, following lung cancer, is the next most frequent malignancy causing this syndrome. A variety of other malignant neoplastic conditions have also been implicated in causing superior vena cava syndrome: Airan and associates4 reported malignant thymoma, Bishop16 and Masuda67 described malignant thymoma, Liu64 acknowledged myeloid leukemia, Osawa76 cited gastric carcinoma, Kew55 named hepatocellular carcinoma, Munjal72 reported liposarcoma, Aggarwal and coworkers2 described mediastinal seminoma, Wakabayashi96 identified metastic ependymoma, Dirix31 mentioned osteogenic sarcoma, and Davis27 cited intrathoracic plasmacytoma as unusual examples of this syndrome. Common nonmalignant conditions predisposing to superior caval obstruction are substernal goiter, which was reviewed by Wesseling98 and reported by de Perrot,28 and fibrosing mediastinitis, reviewed by Esquivel,36 Kulpati,57 and Peters79 (Fig. 177-3). The syndrome has also been described in association with Riedel’s thyroiditis by Abet.1

sharp rise in the use of intravascular devices related to benign obstructions. The superior vena cava syndrome occurs in approximately 3% to 15% of lung cancer patients, and— according to Weinberg,97 Urban,94 Elias,34 Rice,82 and Wilson100—small-cell lung cancer is the most frequent cell type associated with this syndrome. Lymphoma, following lung cancer, is the next most frequent malignancy causing this syndrome. A variety of other malignant neoplastic conditions have also been implicated in causing superior vena cava syndrome: Airan and associates4 reported malignant thymoma, Bishop16 and Masuda67 described malignant thymoma, Liu64 acknowledged myeloid leukemia, Osawa76 cited gastric carcinoma, Kew55 named hepatocellular carcinoma, Munjal72 reported liposarcoma, Aggarwal and coworkers2 described mediastinal seminoma, Wakabayashi96 identified metastic ependymoma, Dirix31 mentioned osteogenic sarcoma, and Davis27 cited intrathoracic plasmacytoma as unusual examples of this syndrome. Common nonmalignant conditions predisposing to superior caval obstruction are substernal goiter, which was reviewed by Wesseling98 and reported by de Perrot,28 and fibrosing mediastinitis, reviewed by Esquivel,36 Kulpati,57 and Peters79 (Fig. 177-3). The syndrome has also been described in association with Riedel’s thyroiditis by Abet.1

Figure 177-1. Appearance of a 54-year-old woman with superior vena cava syndrome following cardiac transplantation. Note facial and palpebral puffiness as well as plethora of the face and chest. |

Figure 177-2. Chest x-ray of a patient with an undifferentiated large-cell bronchogenic carcinoma of the right upper lobe presenting with superior vena cava obstruction. |

The last few decades have ushered a greater use of diagnostic procedures, invasive monitoring, and therapeutic techniques performed intravenously, which have resulted in complications leading to the superior vena cava syndrome. Prolonged transvenous hemodynamic monitoring with pulmonary arterial catheters or injury to the superior vena cava at the time of cardiac catherization have led to caval obstruction and superior vena cava syndrome, as noted by Chetty21 and Ansari.6

Indwelling intravascular devices such as Quinton and Hickman catheters for long-term cancer chemotherapy, antibiotic therapy, and renal dialysis have been reported by Preston,80 Guijarro-Escribano,49 Ozcinar,77 and Greenwell.47 Numerous episodes of superior vena cava syndrome have resulted from scarring and thrombosis of the superior vena cava from transvenous cardiac pacing and defibrillator leads, as reported by Furman,39 Koike,56 Antonelli,7 Goudevenos,44 Santangelo,86 and Aryana10 and their associates. Intravascular devices are now the most common cause of superior vena cava syndrome in benign cases, accounting for 71% of benign obstructions according to Rice.82

Indwelling intravascular devices such as Quinton and Hickman catheters for long-term cancer chemotherapy, antibiotic therapy, and renal dialysis have been reported by Preston,80 Guijarro-Escribano,49 Ozcinar,77 and Greenwell.47 Numerous episodes of superior vena cava syndrome have resulted from scarring and thrombosis of the superior vena cava from transvenous cardiac pacing and defibrillator leads, as reported by Furman,39 Koike,56 Antonelli,7 Goudevenos,44 Santangelo,86 and Aryana10 and their associates. Intravascular devices are now the most common cause of superior vena cava syndrome in benign cases, accounting for 71% of benign obstructions according to Rice.82

Vascular anomalies, aortic aneurysms, and aneurysms of the brachiocephalic vessels, once common in the 1950s and 1960s, are reported by Yavuzer101 to be important but rare causes of superior vena cava obstruction today. Other unusual vascular-related causes such as pulmonary artery aneurysm in Behçet’s disease and giant coronary artery aneurysm have been reported by Kajiya54 and Kumar58 respectively. The superior vena cava syndrome has also resulted from aortic pseudoaneurysms, as reported by Vydt95 and Baldari12 and their associates.

Superior vena cava syndrome may also occur after open cardiac surgical procedures, as reported by Garcia-Delgado,40 Sze,91 and Blanche.17 The present author68 reported a patient who developed the syndrome as a result of narrowing and thrombosis of the superior vena cava following orthotopic cardiac transplantation (Fig. 177-1). Surgical procedures for congenital heart disease that require intracardiac baffles, such as the Mustard operation for transposition of the great vessels, have been reported by Cumming and Ferguson23 to result in superior vena cava syndrome because of scarring.

Miscellaneous causes of superior vena cava syndrome include thoracic trauma, reported by Shah88; sarcoidosis, reported by Fincher37; radiation-induced obstruction, reported by Lee60; and amebic abscess, reported by Gupta.50

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree