The treatment of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) has evolved substantially over the last 10 years in the United States. To capture the important aspects and changes in management, specific and separate guidelines for STEMI were published first in 1990. A comprehensive understanding and integration of both STEMI and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) guidelines as well as systems-of-care issues, reperfusion choices (pharmacologic or mechanical reperfusion), risk stratification, adjunctive medical therapies, technical issues related to PCI, and postreperfusion management is required for the care of these complex patients. This chapter focuses on acute intervention for STEMI. Adjunctive medical therapies are covered elsewhere.

PCI VERSUS THROMBOLYTIC THERAPY

In patients presenting with STEMI, there are three choices for acute revascularization: primary PCI, fibrinolytic therapy, and acute surgical reperfusion (used rarely). Major factors in choosing the initial reperfusion approach include resources available (PCI availability, systems of care, time to treatment), risks of therapy (medical and procedural), patient characteristics (onset of symptoms, ischemic time, presentation status, comorbidities), and anticipated benefits of the reperfusion-specific strategy (

1,

2,

3 and

4). Importantly, no one approach is superior in all regions, clinical settings, or patients. However, all patients should undergo rapid evaluation for reperfusion therapy and have a reperfusion strategy implemented promptly. Compared with fibrinolytic therapy, primary PCI is able to achieve higher rates of TIMI grade 3 flow and infarct artery patency, and lower rates of reinfarction, recurrent ischemia, intracranial hemorrhage, and death in randomized clinical trials (

5).

PCI is associated with an estimated 25% relative risk reduction (odds ratio of 0.75) 1-year mortality (

5). Over the last 10 years in the United States, use of primary PCI has increased dramatically; it is used more than twice as frequently as thrombolytic therapy. (Thrombolytic therapy remains a viable option in cases where PCI is not practical or there is significant reperfusion delay.) This is partly because PCI can achieve higher rates of infarct-related artery (IRA) TIMI grade 3 flow and superior outcomes compared with thrombolytics.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TIME OF ISCHEMIA, MYOCARDIAL SALVAGE, AND SURVIVAL

Benefits of reperfusion therapy are time-dependent. As time from symptom onset (artery occlusion) to reperfusion increases, the myocardium available to salvage decreases, which raises the risk of mortality (

1,

2,

3,

4 and

5). So the greatest myocardial salvage and mortality benefit from reperfusion therapy comes within the first few hours of therapy (

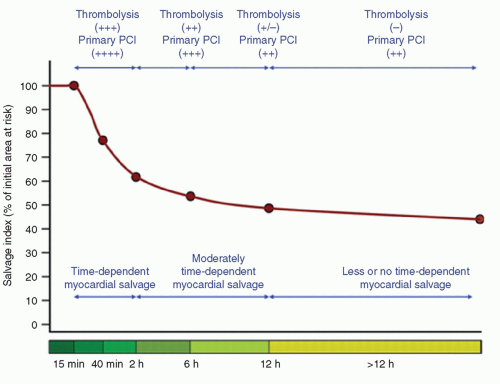

Fig. 17-1). Many modifying factors may

influence the absolute time periods of salvage ability (collaterals, intermittent occlusion, myocardial oxygen consumption, ischemic preconditioning, persistence of residual blood flow, recruitment of collaterals, hibernating). Time-independent benefits of opening the artery have also been suggested to exist, and include improving infarct healing, electrical stability, and reducing in reinfarction.

Current guidelines recommend a systems’ goal of 90 minutes or less from the first medical contact to balloon angioplasty for hospitals that perform primary PCI. A number of variables may influence the total time of reperfusion with primary PCI. These include prehospital variables (symptom onset to first medical contact, prehospital transport, prehospital notification, EMS-administered therapies) and in-hospital factors (diagnosis time, patient variables, cath lab staffing, and procedural time). Symptom-onset-toballoon time and door-to-balloon time are significantly correlated with mortality following primary PCI (

6,

7 and

8). Earlier reperfusion reduces mortality, particularly in those patients presenting early after symptoms onset (<2 hours). Delays in therapy affect mortality benefit to a greater degree in patients who are at higher risk (who have high-risk features: large territory at risk, anterior infarcts, congestive heart failure [CHF], advanced age, and renal insufficiency).

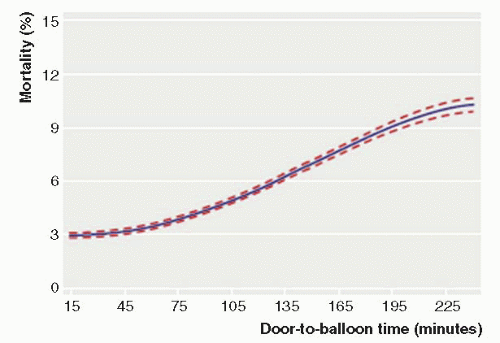

Data from National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) demonstrated a continuous relationship between in-hospital mortality and balloon time, including times below 90 minutes and above 90 minutes, suggesting any delay (even when time is <90 minutes) is associated with an increased mortality risk, as shown in

Figure 17-2 (

7). Similarly, system delays (first medical contact to wire, including prehospital, transfer, and in-hospital delays) have been shown to be independently associated with worse long-term mortality, with each hour of delay associated with a 10% increase in the risk of death (

8,

9).

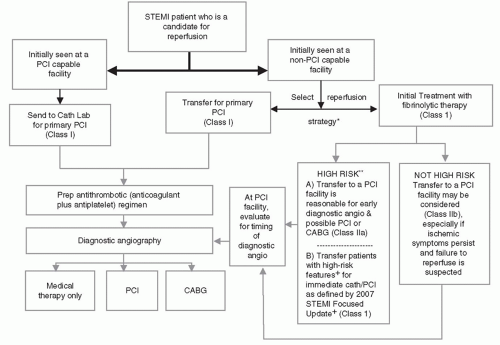

Figure 17-3 and

Table 17-1 summarize current recommendations regarding the triage, treatment, and transfer of patients presenting with STEMI.

Only in the rarest of circumstances, such as when there is a known and anticipated significant PCI delay (>120 minutes), should thrombolytics be considered in patients presenting to hospitals with PCI capability (e.g., catheterization lab not working or available; or staff not available to perform PCI).

Tables 17-2 and

17-3 summarize guidelines for coronary angiography and indications for PCI in STEMI patients.

HOSPITALS WITHOUT PCI CAPABILITY

For STEMI patients presenting to hospitals without primary PCI capability, the decision to use fibrinolytic therapy or transfer the patient to another facility for primary PCI must be made first. In general, a hospital without primary PCI capability should have an established treatment plan designating which primary reperfusion strategy it will generally use. The choice of initial STEMI treatment should be based on a predetermined, institution-specific, protocol (plan). If the referring hospital and the receiving PCI hospital have established a protocol that can minimize transfer delays, then transfer for primary PCI is generally recommended. Primary PCI performed within 120 minutes (<120 minutes from first medical contact to device) should be the systems’ goal for these interhospital transfer patients (

10,

11). For hospitals without such a plan, fibrinolytics should be the default therapy of choice, if the patient is eligible.

Note that primary PCI, irrespective of time delay, is indicated in patients with STEMI who develop severe heart failure or cardiogenic shock and are suitable candidates for revascularization as soon as possible (Class I, LOE B) (

12). In addition, immediate transfer of patients from non-PCI hospitals to PCI-capable facilities following fibrinolysis is recommended as part of a pharmacoinvasive approach in high-risk patients. For these reasons, hospitals without PCI should have an established transfer mechanism for STEMI patients.

SURGICAL AND NONSURGICAL HOSPITALS FOR PRIMARY PCI

Primary PCI without surgical backup should not be performed at institutions without a proven plan for rapid transport to a cardiac surgery hospital or without appropriate hemodynamic support capability for transfer.

It is important to recognize that volume-outcome relationships exist (on both institutional and operator levels), but may be modified by experience. Overall, the ideal total procedural institutional volume is >400 PCI per year (Class I), though volumes of 200 to 400 PCI per year are acceptable (Class IIa). Specifically for primary PCI, the lowest in-hospital mortality threshold was at institutions performing >36 per year according to the NRMI 2 data. Therefore, Class I indications for primary PCI include performance at high-volume centers (>400 cases/y), ideally >36 primary PCI/y. Recommended individual operator volumes include ≥75 PCIs yearly with at least 11 being primary (Class I) (

1,

2). Primary PCI is not recommended (class III—no benefit) at low-volume hospitals (<200/year) by low-volume operators (<75/year).

Table 17-4 lists the guidelines for operator and hospital volume.

Table 17-5 lists recommendations for PCI without on-site surgery.

INDICATIONS FOR PRIMARY PCI (OF THE INFARCT ARTERY)

The following are the ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines Class I recommendations for PCI:

Primary PCI should be performed in fibrinolytic-therapy-ineligible patients who present with STEMI within 12 hours of symptom onset.

Primary PCI should be performed as quickly as possible, with a goal of medical contact-to-balloon (door-to-balloon) time of within 90 minutes.

If the symptom duration is within 3 hours and the expected door-to-balloon time minus the expected door-to-needle time is within 1 hour, primary PCI is preferred. However, if this duration is >1 hour, fibrinolysis is generally preferred.

Primary PCI should be performed for patients younger than 75 years with STEMI or new left bundle branch block (LBBB) who develop shock within 36 hours of myocardial infarction (MI) and are suitable for revascularization.

Primary PCI should be performed in patients with severe CHF and/or Killip Class 3 and onset of symptoms within 12 hours.

Nearly all STEMI patients presenting within 12 hours of symptom onset (with either clinical or electrocardiographic evidence of ongoing ischemia, or with ongoing symptoms) are candidates for primary PCI (including those with true posterior infarcts, or other equivocal electrocardiography [ECG] findings such as LBBB and with a newly occluded artery in a clinical setting consistent with STEMI). Only in patients in whom the risk of revascularization outweighs benefit, or when the patient or designee does not agree to the procedure, would cath and PCI be considered inappropriate. The greatest mortality benefit of primary PCI is in patients who present early or are at highest risk; for example, with cardiogenic shock, an absolute 9% reduction in 30-day mortality was observed with PCI than with medical stabilization (

12)

Primary PCI is also clearly indicated for patients presenting within 12 to 24 hours of symptom onset and there is ongoing ischemia. Recent guidelines recognize that there is an indication for primary PCI in 12 to 24 hours with either clinical or electrocardiographic evidence of ongoing myocardial injury (

2).