Standard Thymectomy

Francis C. Nichols

Victor F. Trastek

The thymus gland continues to present challenges to thoracic surgeons. The thymus is the site of origin of benign and malignant neoplasms; it also is involved in cellular immunity and certain aspects of cellular immunity.

Following the report by Alfred Blalock and associates1 of successful resection of the thymus in a 26-year-old woman with myasthenia gravis (MG) and a thymic cyst, surgical resection of the thymus became a treatment option for this disease. In 1944, Blalock published a total of 20 cases of MG treated by a transsternal thymectomy.2 In the following decade, numerous studies from England and the United States, including those by Clagett and Eaton4,5 at the Mayo Clinic, continued the debate as to the role of thymectomy in treating MG. With time and the refinement of perioperative care, the results of thymectomy improved, so as to validate the benefit of the operation as a significant part of the overall treatment of the myasthenic patient.

Surgical approaches for thymectomy include transsternal and transcervical thoracic surgery as well as video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), there being proponents of each. Regardless of the approach, the basic principles of thymic surgery should include mediastinal exploration, en bloc resection of the thymus gland including the cervical poles and adjacent mediastinal fat, protection of the phrenic nerves, and the prevention of intrapleural dissemination. For patients with thymoma, a full median sternotomy is commonly used. For patients without a thymoma requiring thymectomy, resection through a partial sternotomy is a procedure we commonly employ.

Surgical Anatomy

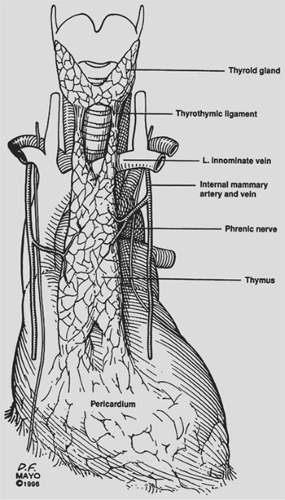

The thymus is a bilobed anterior mediastinal structure overlying the pericardium and great vessels (Fig. 182-1). Midline fusion of the thymic lobes gives the gland its H-shaped configuration. Bilateral upper horns extend into the neck, with attachment to the thyroid gland via the thyrothymic ligament. Lower horns are draped over the pericardium, attaching to the pericardial fat pad. Occasionally one or both lobes may lie posterior to the innominate vein instead of anterior to it. Rare thymic locations include partial or complete failure of descent of one or both thymic lobes and aberrant islands of thymic tissue in the neck, mediastinum, pericardial fat, or within the pulmonary parenchyma. Masaoka and associates6 found a 72% incidence of microscopic deposits of thymic tissue in the

mediastinal fat. Jaretzki and colleagues5 found thymic tissue in the neck outside of the normal thymic cervical extensions in 32% of their patients.

mediastinal fat. Jaretzki and colleagues5 found thymic tissue in the neck outside of the normal thymic cervical extensions in 32% of their patients.

The arterial blood supply comes superiorly from small branches of the inferior thyroid arteries, laterally from the internal mammary arteries, and inferiorly from pericardiophrenic branches. Venous drainage is primarily via a single central vein or multiple branch veins emptying into the left innominate vein. Small veins accompanying the arteries may partially account for the venous drainage.

The proximity of the phrenic nerves to the thymus gland is of critical importance. Both phrenic nerves are intimately associated with the thymus as they pass from the neck into the chest in the region of the thoracic inlet. Knowledge of this anatomy is crucial for successful postoperative outcome, since inadvertent injury to the phrenic nerves can have catastrophic respiratory consequences, particularly in myasthenic patients.

In the newborn, the thymus gland reaches a mean weight of 15 g. By puberty the gland attains a mean weight of 30 to 40 g. Following puberty and continuing throughout adulthood, thymic involution usually occurs, with the gland eventually decreasing to a weight of 5 g to 25 g. Ultimately the thymus is almost totally replaced by fat.

Indications

Indications for thymectomy include resection of a thymic mass, MG in selected patients, or both. Approximately 10% to 15% of patients with MG will have an associated thymoma, whereas 30% or more of patients with thymoma will have MG.

Preoperative Evaluation

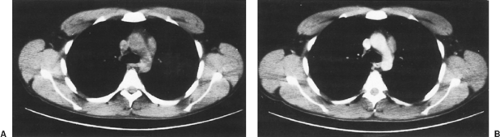

Preoperative evaluation of a patient with an anterior mediastinal mass should include computed tomography (CT) with contrast enhancement to rule out vascular invasion and allow for better delineation of the mediastinal mass (Fig. 182-2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may accomplish these same goals. If a patient presents with an anterior mediastinal mass suspicious for thymoma and vascular abnormalities have been ruled out, resection is indicated. Transthoracic needle aspirates are controversial but may be helpful in the diagnosis of thymoma. Additional preoperative evaluation should be directed toward the detection of associated MG. Similarly, patients being considered for thymectomy because of MG should have preoperative CT scanning to search for an associated thymoma.

Preoperative Preparation

Patients undergoing thymectomy for MG are candidates for operation only if their medical condition is optimized. A team approach in the care of myasthenic patients undergoing thymectomy is advocated. This includes anesthesia, neurology, and the surgical team being involved preoperatively, intraoperatively, and postoperatively. If the myasthenic patient cannot be stabilized with medication, preoperative plasmapheresis is required prior to thymectomy. Seggia and associates8 found that plasmapheresis significantly improved respiratory function and muscle strength in myasthenic patients undergoing thymectomy, thus leading to a reduced hospital stay and lower cost.

Preoperative anesthetic medication is minimal, usually consisting only of atropine and a mild sedative. Preoperative anticholinergic medications are avoided. Myasthenic patients pose no particular anesthetic problems, although muscle relaxants should be avoided. Deep anesthesia is maintained by an inhalational agent and short-acting narcotic. During the operative procedure, the airway and ventilation can be controlled with a single-lumen endotracheal tube.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree