CHAPTER 37 Staging Techniques for Carcinoma of the Esophagus

In the United States in 2008, there were 16,470 estimated new cases of esophagus cancer diagnosed and 14,280 estimated deaths.1 Worldwide, the overall survival from esophageal cancer remains dismal at less than 10% at 5 years2 because fewer than half of the patients will be eligible for potentially curative resection at the time of presentation. The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma continues to increase in the United States, with a more than 20% increase per year in white men in particular but also a significant rise in African-American men and white women.3

Although the prognosis of patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma remains poor, there have been improvements in the staging modalities available to enhance the appropriate selection of treatment for patients. In addition, significant advances have been made in less invasive therapeutic modalities, from endoscopic resection of intramucosal cancers to minimally invasive approaches for esophagogastrectomy. Improvements in early detection of the disease, selection of appropriate treatment for patients, and surgical approaches may eventually translate into improved overall survival rates. Currently we see 3-year survival rates for patients with stage I esophageal adenocarcinoma reported from 65%4–6 to at least 80% at 5 years for carefully staged patients.7,8 Historically, however, esophagectomy has been associated with mortality rates exceeding 20%9; thus, oncologists have been reluctant to refer patients for potentially curative surgical resection. With modernization of approaches and improved perioperative care, the surgical mortality rates after esophagectomy have improved to less than 4% in the past decade.5,6,8 Esophagectomy, however, should be considered a potentially curative option and not a palliative modality, considering the negative impact on quality of life after potentially palliative resection.10 More palliative options are now currently available in the form of stents and laser therapy,11 and resection may be reserved for the significantly bleeding or perforated tumor. Accurate staging is also important to determine the best mode of palliation for patients with stage IV disease. The information gained may allow a realistic discussion with the family. For example, does a patient benefit from a feeding tube if the disease is stage IV?

In addition to early detection of this disease, identification of early-stage disease with accurate staging tests should allow optimal selection of surgical candidates. Routine noninvasive preoperative staging modalities available at most institutions should include endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), and positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET/CT). Previously, only CT scans, bone scans, and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were available for diagnosis of distant disease, or patients would undergo potentially morbid surgical exploration only for their cancer to be deemed unresectable. Patients with early-stage disease benefit from surgical resection, whereas patients in an advanced stage may benefit from palliative options to improve quality of life. Patients assigned to an intermediate stage can benefit from neoadjuvant therapy followed by restaging and surgical resection with curative intent. Although clinical trials of neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation have generally not shown a consistent survival benefit,12–15 a few individual studies and a meta-analysis have shown some benefit.16–19 It is increasingly becoming the standard of care to offer neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation to patients with clinical stage T3 or N1 esophagus cancer.17,20–22 The earlier studies did not have PET or PET/CT available to help with restaging, and this absence may have contributed to esophagectomies in patients with metastatic disease. In addition, because neoadjuvant treatment is still considered controversial, accurate staging is important to determine which patients may be eligible for clinical trials, to assess response to treatment with PET and CT scans, and then to determine which patients should be offered potentially curative esophagectomy.

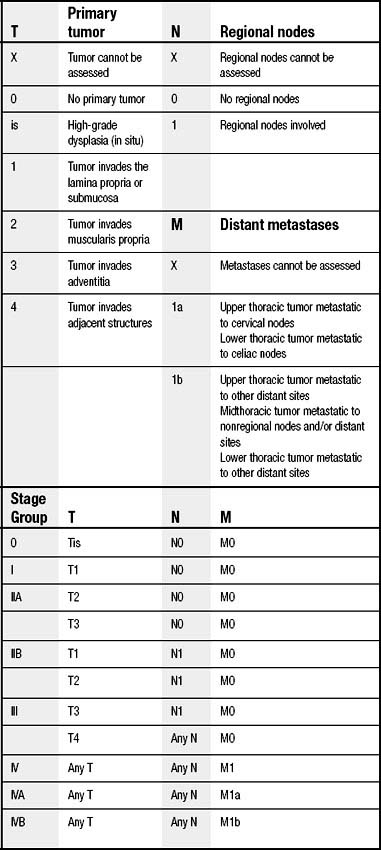

ESOPHAGEAL CANCER TNM STAGING

The current staging system for esophageal cancer follows the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM system of T for tumor, N for regional nodal status, and M for presence or absence of distant metastases (Table 37-1).23 The TNM staging system is in the process of being revised. Several changes may include subdividing T1 to include T1a for intramucosal cancers and T1b for submucosal lesions. This T stage modification is based on the incidence of lymph node involvement and subsequent survival differences for tumors of increasing depth. In addition, as has been done for pathologic staging of other malignant neoplasms,24–26 there will also likely be a subdivision of the nodal stage based on number of lymph nodes involved with metastases. Again, this change is based on several studies from different esophageal groups in the United States that have found significant survival differences based on absolute number of positive lymph nodes,27–31 absolute number of negative lymph nodes,32 and ratio of positive to negative lymph nodes.31,30,33

STAGING BY ENDOSCOPIC ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Endoscopic ultrasound staging of esophageal cancers was first advanced in the literature by Lightdale34 in 1992. In the next decade, the modality became a standard part of staging of esophageal cancer in newly diagnosed patients.35 Before EUS, CT was the primary modality available to decide whether to proceed with an esophagectomy for an otherwise medically fit patient presenting with esophagus cancer, although MRI and bone scans were sometimes indicated by clinical presentation. Now EUS is available to help determine locoregional stage of esophagus cancer as well as distant disease by providing cytology of liver, adrenal, or celiac lymph nodes metastases.

With increased utility of preoperative chemoradiation, especially after the Walsh study,36 EUS helped determine the locoregional stage of the cancer so that neoadjuvant treatment could potentially be offered to those with locally advanced disease. Although clinical signs and symptoms can determine T stage with a fair degree of accuracy, with substernal chest pain, dysphagia, and weight loss all being highly suggestive of T3 or T4 disease,37 symptoms alone are probably not enough to determine surgical resectability. In addition, EUS has improved on CT evaluation of distant metastatic disease by providing fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and cytologic confirmation of hepatic or celiac lymph node metastases with accuracy rates of 90%.38,39

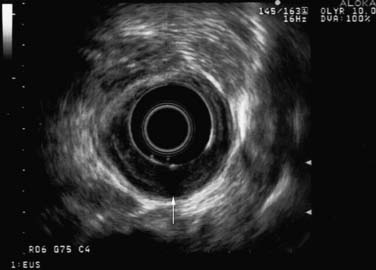

Conventional EUS is carried out with conscious sedation by use of the 360-degree radial mechanical echoendoscope with a 7.5-MHz ultrasound probe. Conventional EUS is the best approach to assess depth of primary tumor into the esophageal wall (Fig. 37-1). For EUS-guided FNA of suspicious lymph nodes, a curved linear array echoendoscope is used with a 22- or 25-gauge needle. A 7.5-MHz or lower frequency endoscope is better than the high-frequency one for assessment of regional lymph nodes because of the greater depth of visualization. Endoscopic criteria for potentially malignant lymph nodes include at least two of the following characteristics: round, discrete, hypoechoic, and a dimension of more than 1 cm.40,41 EUS imaging of nodes alone is not specific enough, but FNA of the suspicious nodes can result in a specificity rate of up to 95%.42

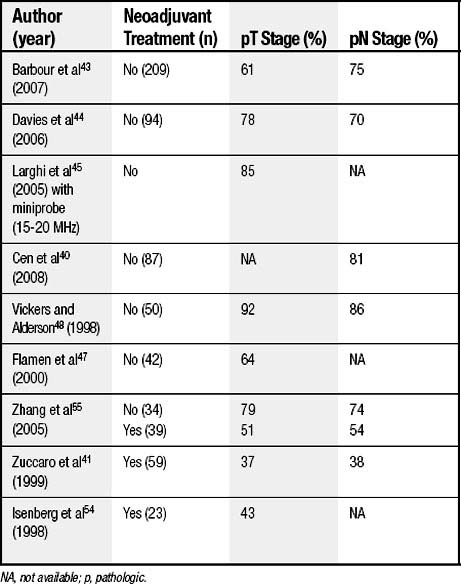

EUS remains the most accurate modality for determination of T stage, with accuracy rates ranging from 64% to 80% for the low-frequency probe38,43,44 and up to 85% to 92% for the high-frequency probe.38,40,45 Accuracy can be calculated only when patients have undergone histologic confirmation of the tumor and nodal status. The accuracy of EUS for staging of T and N stage in the most recent series of patients since the mid-1990s is summarized in Table 37-2. As summarized, EUS staging is indicated before initiation of chemotherapy or radiation therapy. The accuracy rates as confirmed by pathologic staging decrease by 25% to 50% for both T and N stages when it is done after induction therapy. EUS is more accurate for T3 and T4 stages38,44 (80% to 90%) than for T1 and T2 stages (74%).44 In a large series of more than 200 patients with pathologic confirmation of the tumor and nodal stages, most EUS staging errors were understaging of T0 and T1 and overstaging of T2.46 EUS accurately staged T3 and T4 lesions in 85% of cases.43 In another series of 47 patients undergoing surgical resection for adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, EUS overstaged T stage in 19% of the patients and understaged it in 17%.47

Table 37–2 Accuracy of Endoscopic Ultrasound Staging in Various Series with Pathologic Stage Available

In studies with pathologic confirmation, the accuracy rates for N stage range from 70% to 86%.38,40,43,44,48 Before FNA-guided biopsy of lymph nodes by EUS was applied, the false-negative rate of EUS for nodal stage exceeded 33%.47,49

Although EUS has added much to the clinical staging and management of esophageal cancer patients, it still is limited by malignant stenoses preventing staging of the primary tumor. In these cases, however, tumor obstruction almost always represents T3 or T4Nx.48 In addition, the probability of a T3 or T4 tumor being N1 exceeds 80%.50

With the continued expansion of endoscopic therapy for early esophageal cancers, accurate staging of T1 adenocarcinoma with EUS will be important to determine which patients may be offered endoscopic therapy with potential cure and which patients should undergo esophagectomy. From experienced EUS groups, the accuracy of staging of an intramucosal (T1a) cancer was 82% to 94%.38,40,51 A T1b cancer has about a 20% likelihood of lymph node metastases versus the intramucosal lesion, which is less than 5%; thus, the EUS T stage may help in deciding between endoscopic and surgical resection.52 EUS before endoscopic resection of T1 tumors remains controversial, and resection may be diagnostic.

Endoscopic Ultrasonography and Neoadjuvant Therapy

Although EUS is feasible in 70% of patients after neoadjuvant chemoradiation,53 its accuracy rate with current neoadjuvant modalities drops below 50%.41,54 It overstages the tumor depth and nodal status in more than 49% and more than 38%, respectively.55 The accuracy for T stage after chemoradiation at current radiation doses of 45 Gy ranges from 37% to 43%.41,54 Radiation fibrosis causes overstaging or understaging of T stage about 40% of the time.53,56 T stage by EUS after chemotherapy may be accurate only when the tumors do not respond to the chemotherapy.41 EUS essentially is not recommended after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation because of the low accuracy rate54 secondary to the postinflammatory changes,41,57 although post-chemoradiation CT or endoscopy alone is not as good as EUS in assessing treatment response.58

Metastatic Disease

EUS is also helpful in confirming metastases to celiac lymph nodes, which assigns the patient to stage IV cancer.42,59,60 Celiac lymph nodes could be evaluated in 95% of 62 patients in Reed’s series from 1999, and in this group, EUS sensitivity was 72% and specificity 97%.59 The presence of celiac lymph node metastases as detected by EUS has also been associated with a worse survival for all T stages. In another study from the Medical University of South Carolina, the authors concluded that the 5-year survival rate of patients without celiac nodal involvement by EUS was three times better than that of patients with celiac lymph node involvement (39.8 versus 13.8 months).60 EUS can also be helpful in evaluating and allowing biopsy of liver metastases.61 In a study of 132 patients, EUS-FNA of noncystic liver lesions confirmed liver metastases in 20% of the cases, and EUS was superior to CT in quantifying liver metastases, especially in cases in which the metastases were too small to be characterized by CT scan.61

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

Accuracy rates of CT scanning for assessment of depth of esophageal and gastroesophageal junction cancers are notoriously poor: 33% for T2, 0% for T3, and 50% for T4 for an overall rate of 15%. CT tends to understage depth of penetration,62 although the overall accuracy of CT for T stage was 59% in more recent series.38,49,62,63 CT is used to identify distant metastases and suspicious regional nodes more than tumor depth. Historically, nodal staging by CT averaged 50% for node-positive patients,62 whereas the combination of EUS and CT for detection of regional nodal involvement accurately was 82% in a series of 42 patients undergoing surgical resection.50 The sensitivity of CT staging of celiac lymph nodes was only 8% in slightly older series, although the specificity was 100%,59 but it was only 64% accurate for diagnosis of stage IV disease by solid organ metastases or distant lymph node metastases in 74 Belgian patients.47

Before the advent of CT scanning for staging of esophagus cancer, other noninvasive tests including linear tomography and bone scans accurately staged esophagus cancer in less than 30% of cases.64 Routine CT scanning has improved the detection of distant metastases, but it generally has been replaced by the more sensitive PET/CT. CT scanning may still have a role in evaluating chemoradiation response, however. Some groups have suggested that a reduction in maximal cross-sectional area of the tumor on CT scanning may be helpful in assessing chemoradiation response preoperatively.38,54 Similarly, earlier studies suggested that preoperative CT width of the cancer may be a prognostic factor,58 even without neoadjuvant downstaging.65 New interest is developing in this staging of tumor measurements on radiographic measurements, with assessment of treatment response based on tumor length.66

POSITRON EMISSION TOMOGRAPHY

Initial Staging

PET scans initially and currently use 18F-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose ([18F]FDG) as the tracer for glucose metabolism. [18F]FDG is taken up into the cell and phosphorylated but cannot be metabolized as glucose 6-phosphate and instead is trapped within cells using high rates of glucose. Patients must fast for 4 to 6 hours before the PET scan so that they are normoglycemic at the time of the study. Forty to 60 minutes after intravenous injection of 10 to 15 mCi of FDG, the scan is obtained with the patient supine. The minimum lesion size that can be detected by PET scan alone is 5 mm,67 although with PET/CT, we may see improvements in the resolution as lesion size and intensity influence detectability. PET is very sensitive at detection of primary tumor, with the primary tumor being hypermetabolic in more than 95% of cases.47,68,69 One of the big advantages of PET scanning over CT is the three-dimensional imaging with PET. This modality also is more likely than CT to identify second primary tumors.68 PET is not typically used to diagnose esophageal cancer, however, but instead is used to evaluate regional nodal disease and distant metastases. Lymph node status is the most important prognostic predictor for patients with potentially resectable disease,70 and clinical staging of lymph nodes currently may lead to induction therapy. Thus, optimal clinical staging of lymph nodes is an important part of esophageal cancer workup. From many series, sensitivity and specificity of PET are 51% and 84% for detection of regional nodal disease and 67% and 97% for metastatic disease.67 PET/CT improved the accuracy of PET alone for identification of malignant lymph nodes in a series of 39 patients because CT improved the localization of the PET tracer.71 In this particular study, small lymph nodes (6 to 11 mm) that were negative on PET were detected with PET/CT. PET findings for detection or elimination of metastatic disease have been shown to change management of the patient in about 20% of cases staged by CT initially.67

There is currently growing enthusiasm for use of PET and SUV data to give prognostic information as well as response to neoadjuvant therapy. Although it is controversial whether T stage correlates with PET SUV, with Flamen and coworkers47 finding no relationship between primary tumor SUV and pathologic T stage or extent of nodal metastases, Cerfolio and Bryant72 did find a significant correlation between T stage and N stage with increasing SUV. In general, PET is not considered a useful determinant of T stage.67 In the PET study by Downey and associates73 of patients receiving neoadjuvant treatment, pretreatment SUV, however, did not correlate with survival in 39 esophagectomy patients.

The first studies demonstrating that PET would be useful for staging of esophagus cancer came from Flanagan and colleagues at Washington University. This group found that in 29 patients who underwent curative surgery (19 with adenocarcinoma), PET scan accurately detected regional nodal disease in 76% of the patients and distant metastases in 93% of the patients. PET identified regional nodal involvement twice as often as CT did in 21 patients undergoing esophagectomy for adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma and improved detection of metastatic disease by 80% (45% by CT and 82% by PET and CT).68 For detection of stage IV disease in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, PET alone had sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy rates of 74%, 90%, and 82% compared with rates of 41%, 83%, and 64% for CT scan, respectively.47 Small (<1 cm) hepatic metastases were missed by both PET and CT scans in one patient, and in a second, a pancreatic metastasis was missed.74 The authors concluded that PET changed clinical management in 17% of 36 patients with adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma.74 False-positive results on PET scanning of esophagus cancer patients can result from granulomatous disease, reactive hyperplasia, or local extension of tumor misinterpreted as regional nodal involvement.47,74 False-negative regional lymph node involvement can result from occult micrometastatic disease in normal-sized nodes and in nodes adjacent to the primary tumor, where the PET uptake of the primary tumor obscures the nodal uptake. False-negative findings of stage IV disease by PET can result from peritoneal metastases, small (<1 cm) or superficial hepatic metastases, and presumably small lung lesions.47

Results of the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0060 trial of PET staging in esophagus cancer were published in 2007.75 This is the only intergroup trial that has looked at PET scans in esophageal cancer to determine whether PET can improve on an acceptable 5% rate of metastasis detection and hence prevent unnecessary surgery for esophageal cancer patients with metastatic disease. All patients underwent a CT scan of the abdomen and chest first; if that was normal, they had a PET scan to look for stage IV disease. Although tissue confirmation of PET-positive suspicious lesions was part of the study algorithm, not all patients were able to undergo confirmatory biopsies of PET-positive areas. Indeed, two patients who did undergo procedures sustained complications after biopsy or after an adrenalectomy for a false-positive PET result. Of the 145 patients who had a PET scan negative for metastases and who underwent potentially surgical resection, 5.6% developed recurrent cancer (location not otherwise specified) within 6 months of surgery. The group concluded that confirmed metastatic disease was detected in 4.8% of patients otherwise potentially eligible for curative surgery after body CT staging and as-needed brain or bone imaging and that tissue confirmation is important for avoiding the 3.7% false-positive rate resulting from PET scanning of these patients. In the PET study of 39 patients undergoing induction treatment, PET identified distant metastatic disease in 15% of patients, with tissue confirmation or support by another imaging modality.73

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree