Chapter 43 Splanchnic and Renal Artery Aneurysms

Splanchnic Artery Aneurysms

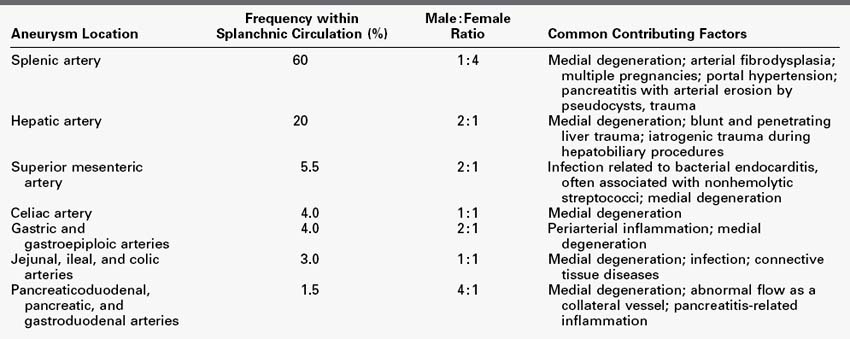

Splanchnic artery aneurysms are an uncommon but important vascular disease (Table 43-1). Nearly 22% of these aneurysms appear as surgical emergencies, including 8.5% that result in the patient’s death. The major splanchnic vessels involved with these macroaneurysms, in decreasing order of frequency, are the splenic; hepatic; superior mesenteric; celiac; gastric and gastroepiploic; jejunal, ileal, and colic; pancreaticoduodenal and pancreatic; and gastroduodenal arteries.

The clinical manifestations of splanchnic artery aneurysms have become well defined during the past 3 decades.1–15 Rupture is the most serious complication of these aneurysms (Table 43-2). In many circumstances, endovascular therapy provides a distinct advantage over conventional surgical therapy.2,6,9,15–21 Nevertheless, treatment of certain splanchnic artery aneurysms by open operative therapy remains appropriate.4,8,14,22 The cause, presentation, and management of aneurysms affecting each of the splanchnic arteries deserve separate comment.

Splenic Artery Aneurysms

Splenic artery aneurysms account for 60% of all reported splanchnic artery aneurysms. The frequency of splenic artery aneurysms in the general population approaches the 0.78% incidence noted in nearly 3600 consecutive abdominal arteriographic studies performed for reasons other than suspected aneurysmal disease.22 Women are nearly fourfold more likely than men to have these aneurysms,13,23 although in more contemporary times this female predilection appears to be reduced.24

Four distinct, preexisting conditions are suspected to contribute to the development of splenic artery aneurysms. The first is medial fibrodysplasia with its derangements and thinning of the vessel’s medial smooth muscle. Although medial fibrodysplasia is commonly recognized as a cause of hypertension secondary to its renal artery involvement, approximately 2% of patients exhibiting this disease have splenic artery aneurysms.22 In addition, blood pressure elevations in these patients may contribute to aneurysm development. Coexistence of renal artery medial fibrodysplasia and splenic artery aneurysms has been identified only in women.

Second are the effects of increased splenic blood flow and the altered levels of reproductive hormones that accompany pregnancy. Both have deleterious effects on elastin and other matrix proteins in the splenic artery wall. In past decades, approximately 40% of women harboring these aneurysms had completed six or more pregnancies.22 Given the fact that in contemporary times fewer children are being born to women in Western societies, the frequency of grandmultiparity in women exhibiting these aneurysms has declined to approximately 10%.24

Third, portal hypertension with splenomegaly is associated with splenic artery macroaneurysms in nearly 10% to 15% of patients.25–28 This may result from the higher velocities in splenic blood flow29–30 as well as elevated estrogen activity associated with advanced cirrhosis. There has been an increased recognition of these aneurysms in patients subjected to orthotopic liver transplantation.25,27,31,32 These aneurysms are more common in female than male liver transplant patients, and they appear directly related to the severity of the patient’s antecedent portal hypertension.33,34

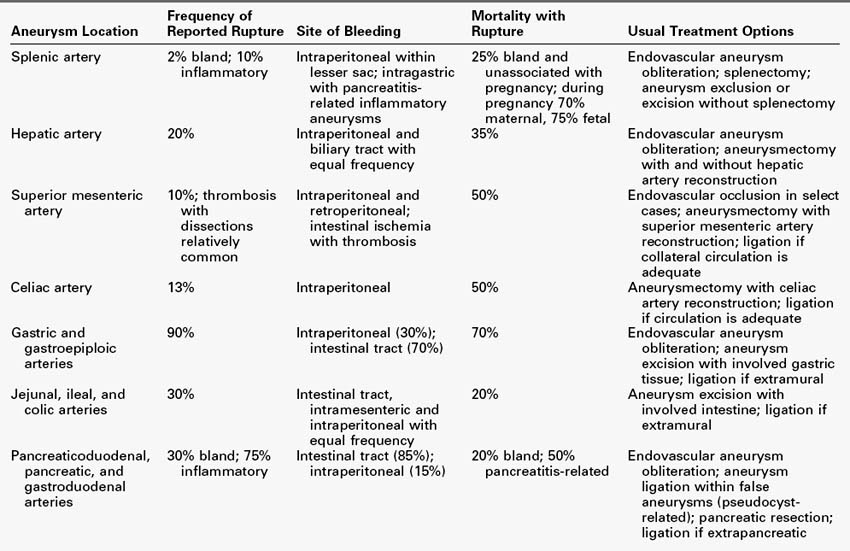

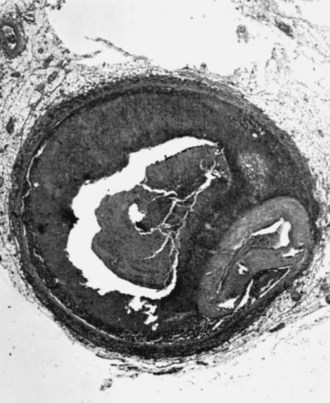

Most splenic artery aneurysms associated with arterial fibrodysplasia, multiple pregnancies, or portal hypertension are saccular and occur at vessel branchings (Figure 43-1). These are true aneurysms, not false aneurysms. Discontinuities exist in the internal elastic lamina of normal vessels at branchings, and subsequent alterations in elastic tissue, such as those occurring during late pregnancy, are apt to produce aneurysmal changes at these sites. Aneurysms unrelated to portal hypertension are multiple 20% of the time. Among patients with portal hypertension and cirrhosis undergoing liver transplantation, multiple aneurysms are even more common.27,33 In contrast, false aneurysms associated with pancreatitis usually involve the main splenic artery and tend to be solitary (Figure 43-2).

Curvilinear or signet-ring calcifications in the left upper quadrant on radiographs are often evidence of a splenic artery aneurysm (Figure 43-3). However, diagnosis is more likely to follow demonstration of the aneurysm during imaging undertaken for some other disease state. Conventional arteriography, ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), CT arteriography, and magnetic resonance arteriography are not only useful in recognizing these lesions, but are often helpful in identifying bleeding aneurysms.

FIGURE 43-3 Splenic artery aneurysms. Radiographic appearance of characteristic signet-ring–like calcifications.

(From Zelenock GB, Stanley JC: Splanchnic artery aneurysms. In Rutherford RB, editor: Vascular surgery, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2000, WB Saunders, p 1371.)

Left upper quadrant or epigastric pain directly referrable to splenic artery aneurysms occurs in a minority of individuals, although some form of abdominal discomfort affects approximately 20% of these patients.22 In this regard, although nearly half the patients having intact aneurysms in a recent review had abdominal symptoms, in no case were the symptoms attributed to the aneurysm.24 In contrast, a 1996 review of 83 cases that included many single case reports noted that 46% of patients had abdominal pain and 25% were in shock.11 The disparity in these publications is attributed to the fact that reviews often summarize spectacular individual case reports that are unlikely to be representative of the usual patient’s clinical course.

Initial bleeding from a ruptured splenic artery aneurysm may be contained within the lesser sac. Eventually, free hemorrhage into the peritoneal cavity occurs and causes vascular collapse. This “double-rupture” phenomenon is often referred to in discussions of splenic artery aneurysms but is, in fact, relatively uncommon. Pancreatitis-related aneurysms are often a source of intestinal hemorrhage after erosion of a pseudocyst into an adjacent artery and subsequently into the stomach or pancreatic ductal system.10,35–37 Arteriovenous fistula formation from rupture of a splenic artery aneurysm into the adjacent splenic vein is a rare but recognized cause of gastrointestinal hemorrhage from esophageal varices resulting from left-sided portal hypertension.38,39

The risk of splenic artery aneurysm rupture is related to its cause. Rupture of bland aneurysms has been generally accepted to be approximately 2%.22 However, the actual rupture risk may be less. In fact, a recent review of 168 patients with these aneurysms reported a rupture rate of zero among those not subjected to surgical therapy.23 Contrary to earlier misconceptions, rupture is just as likely to occur with a calcified aneurysm in a normotensive patient or in a very old patient. In the past, the mortality accompanying rupture of a bland splenic artery aneurysm in a nonpregnant patient has been reported to be 25%.13 Rupture of inflammatory pancreatitis-related aneurysms is approximately 20% and is associated with a 40% mortality rate.

Bland aneurysms in liver transplant recipients appear to be nearly twice as likely to rupture as those in other patients.31,33 Rupture is most likely to occur early in the period after transplantation.25,27 The mortality following rupture of a splenic artery aneurysm in a liver transplant patient exceeds 50%.

Nearly 95% of reported aneurysms first recognized during pregnancy have ruptured.40–44 However, these figures are misleading, in that women develop splenic artery aneurysms during the course of repeated pregnancies, and most of these aneurysms are likely to go unrecognized without rupture. Nevertheless, splenic artery aneurysm rupture during pregnancy represents a serious potential threat to the health of the mother and the fetus. Overall maternal and fetal mortality in these cases has generally been accepted to approach 70% and 75%, respectively. Rupture, even when recognized early enough to allow for operative intervention, still carries a reported maternal of 22% and fetal mortality of 16%.41

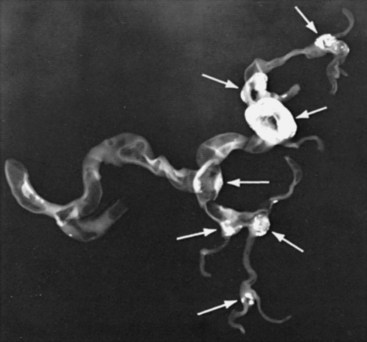

Percutaneous transcatheter embolization using various agents, including differing types of particulate matter, coils, and glue (acrylate derivatives), has become preferred over open operative interventions in the treatment of most splenic artery aneurysms (Figure 43-4).* Nevertheless, splenic infarction, delayed rupture of the spleen, inconsistent and transient obliteration of the anuerysm, and migration and erosion with stricture of adjacent viscera are all recognized complications of endovascular therapy.2,9,24,48–50 Careful follow-up of endovascular-treated patients thus becomes mandatory. Stent-graft exclusion of an aneurysm with maintenance of splenic artery flow may avoid many of the complications attending embolic interventions and is appropriate in select cases.51–54

FIGURE 43-4 A, Splenic artery aneurysm (arrows). B, Aneurysmal occlusion following coil embolization.

(From Upchurch GR, Jr, Zelenock GB, Stanley JC: Splenic artery aneurysms. In Rutherford RB, editor: Vascular surgery, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2005, Elsevier-Saunders, p 1569.)

Splenectomy historically has been the most commonly reported open surgical intrevention undertaken for the treatment of splenic artery aneurysms.11,22 With recognition of the immunologic benefits of splenic preservation, even in the aged, simple ligature obliteration or excision of these aneurysms has become preferable to splenectomy when an open surgical procedure is pursued.55 In select cases, these procedures may be undertaken by a laparoscopic or a robotic approach.56–58

Certain inflammatory splenic artery aneurysms embedded in the pancreas may require distal pancreatectomy. Other aneurysms, especially false aneurysms associated with pseudocyst erosion into the adjacent artery, may be most effectively treated by initially incising the aneurysmal sac and ligating the entering and exiting vessels.36 Pancreatic resection in the former cases depends on the degree of associated pancreatic inflammation and the general condition of the patient.59

Hepatic Artery Aneurysms

Hepatic artery aneurysms account for 20% of all reported splanchnic artery aneurysms60–63; they appear to be more common in contemporary practice.11 Men are twice as likely to be affected as women, although gender differences appear to be less significant in more recent times. More than one third of patients with these aneurysms have other splanchnic artery aneurysms.60 Nontraumatic and nonmycotic aneurysms are most often discovered during the sixth decade of life.

Both penetrating and blunt liver injuries have led to a marked increase in the number of reported hepatic artery aneurysms. Many of these lesions have been recognized as small pseudoaneurysms on CT studies obtained in evaluating major abdominal trauma. Traumatic etiologies are a likely reason that almost half of the reported hepatic artery aneurysms are noted in the intrahepatic arterial branches. Iatrogenic false aneurysms secondary to biliary tract and pancreatic operative trauma are well recognized. In particular, pseudoaneurysms associated with percutaneous and therapeutic hepatobiliary procedures are relatively common.2,11,64

Hepatic artery aneurysms are usually solitary; they are extrahepatic in nearly 80% of cases and intrahepatic in 20% (Figure 43-5). Arteriosclerosis is considered a secondary event rather than an actual cause of any of the various types of hepatic artery aneurysms.

FIGURE 43-5 Large common hepatic artery aneurysm affecting the distal artery at the origin of the proper hepatic artery.

(From Zelenock GB, Stanley JC: Splanchnic artery aneurysms. In Rutherford RB, editor: Vascular surgery, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2000, WB Saunders, p 1374.)

Most hepatic artery aneurysms are asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally during imaging for other illnesses.11,62,63 Nontraumatic hepatic artery aneurysms are occasionally symptomatic, in which case they characteristically produce right upper quadrant and epigastric pain. Acute expansion of hepatic artery aneurysms can cause severe abdominal discomfort, similar to that of pancreatitis. Large aneurysms may cause obstructive jaundice.65

The incidence of hepatic artery aneurysm rupture remains ill-defined, but the rupture rate in contemporary times approaches 20%.7,60 However, bleeding has accompanied more than half of the aneurysms from institutions reporting large numbers of iatrogenic intrahepatic aneurysms.2 Bleeding from ruptured hepatic artery aneurysms occurs equally into the biliary tract and into the peritoneal cavity. In the case of the former, hemobilia is often evident, manifested by biliary colic, hematemesis, and jaundice.66,67 Chronic gastrointestinal hemorrhage is an uncommon but recognized sequela of aneurysm rupture into the biliary tract. Intraperitoneal bleeding is usually associated with false aneurysms caused by periarterial inflammatory processes eroding into the hepatic vessels. Multiple nonarteriosclerotic aneurysms have an apparent greater risk of eventual rupture.60 The reported overall mortality rate attending aneurysm rupture approaches 35%, although recent experience suggests that mortality is lower.

Percutaneous transcatheter obliteration of hepatic artery aneurysms with balloons, coils, various types of particulate matter, and even thrombin, is often preferred over an open surgical intervention (Figure 43-6).2,15,64,68–70 Transcatheter embolization may be only transiently successful, and repeated embolization or eventual surgical therapy may be required to adequately treat certain patients. Endovascular stent graft exclusion of select aneurysms avoids some of the limitations accompanying embolization alone.71–75

Common hepatic artery aneurysms in the past were usually treated by open ligation, aneurysmectomy, or aneurysm exclusion, without arterial reconstruction.11,17,61,76 If liver blood flow was compromised after hepatic artery occlusion, a direct vascular reconstruction needed to be undertaken with a prosthetic or autologous graft.8,9,60 Hepatic ischemia is most likely to accompany treatment of aneurysms involving the proper hepatic artery or its extrahepatic branches and, whenever possible, arterial reconstruction of these vessels is favored following aneurysmectomy.9,17 Casual ligation of extrahepatic branches to control bleeding from intrahepatic aneurysms may cause liver necrosis, and in this setting hepatic territory resection may be necessary in rare cases.62

Superior Mesenteric Artery Aneurysms

Aneurysms of the proximal superior mesenteric artery are the third most common splanchnic artery aneurysm, accounting for 5.5% of these lesions. Men are affected nearly twice as often as women.77 An infectious etiology associated with bacterial endocarditis was more common in the past.78–80 Nonhemolytic streptococci account for the majority of mycotic lesions encountered in contemporary practice. Superior mesenteric artery aneurysms may also be related to medial degeneration, periarterial inflammation, and trauma. Arteriosclerosis, when present, is considered a secondary event rather than an etiologic process.

Superior mesenteric artery aneurysms are usually recognized during imaging studies for other diseases. The majority of these aneurysms are asymptomatic. When symptomatic, there is usually an acute expansion, dissection, or rupture of the aneurysm. Rupture affected a little more than one third of cases reported from a large health care system.77 However, a rupture rate near 10% is more likely representative of contemporary practice. Mortality approaches 50% with rupture. Aneurysmal dissection is believed more common than rupture (Figure 43-7).81–84 The unique location of dissecting aneurysms near the origins of the inferior pancreaticoduodenal and middle colic arteries place the distal mesenteric circulation at risk if these vessels become occluded. Thrombosis of the superior mesenteric artery in such cases results in a loss of the usual collateral networks from the adjacent celiac and inferior mesenteric arterial circulations. Occasionally, the latter causes intestinal ischemia with pain suggestive of abdominal angina. Symptomatic, expanding aneurysms and those greater than 2 cm diameter warrant interventional therapy.

FIGURE 43-7 Superior mesenteric artery aneurysm associated with a dissection compressing the arterial lumen.

(From Zelenock GB, Stanley JC: Splanchnic artery aneurysms. In Rutherford RB, editor: Vascular surgery, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2000, WB Saunders, p 1376.)

Endovascular stent-graft placement has appeal for selected superior mesenteric artery aneurysms.85–88 Although late complications of thrombosis and infection may accompany endovascular stent-graft therapy, the early morbidity and mortality are much less than what occurs with open surgical procedures. Certainly, obliteration of these aneurysms by coils or direct thrombin injection may be preferred in high-risk patients with discrete aneurysm necks.77,89

Open surgical ligation of superior mesenteric artery aneurysms without arterial reconstruction has proved possible in certain cases, especially for aneurysms associated with prior arterial obstruction and an adequate collateral circulation to the midgut structures.77,90 In fact, ligation has been the most common open surgical means of managing these lesions. If trial clamping results in bowel ischemia, then intestinal revascularization is required.

Celiac Artery Aneurysms

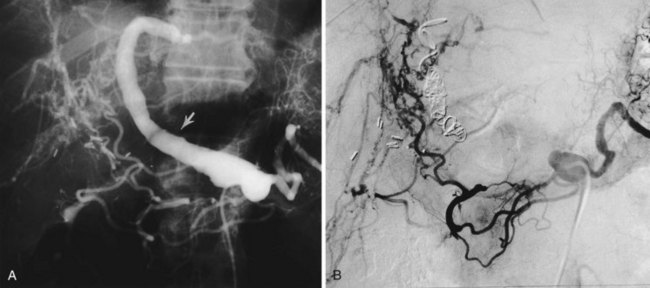

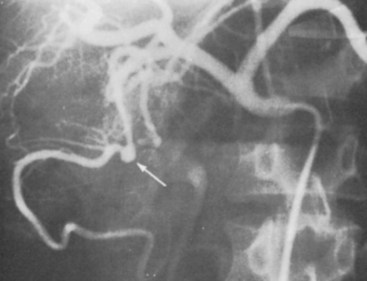

Celiac artery aneurysms account for 4% of all splanchnic artery aneurysms. Men and women appear to be equally affected. Half the celiac artery aneurysms encountered before 1950 were mycotic, although infectious lesions have been relatively uncommon in recent years.91 Most aneurysms are associated with medial defects. Aortic aneurysms affect nearly 20% of these patients, and nearly 40% have other splanchnic aneurysms. Arteriosclerosis is a frequent finding, but it is considered a secondary process, as in the case of other splanchnic artery aneurysms. Celiac artery aneurysms are usually saccular, affecting the distal trunk of this vessel (Figure 43-8), with some evolving from poststenotic dilatations caused by preexisting occlusive disease or median arcuate ligament entrapment and narrowing of the proximal celiac artery.

FIGURE 43-8 Celiac artery aneurysm (arrow) affecting the distal trunk of the vessel.

(From Whitehouse WM, Jr, Graham LM, Stanley JC: Aneurysms of the celiac, hepatic, and splenic arteries. In Bergan JJ, Yao JST, editors: Aneurysms: diagnosis and treatment, New York, 1981, Grune and Stratton, p 407.)

Most contemporary celiac artery aneurysms are asymptomatic or are associated with vague abdominal discomfort.11,91,92 Antemortem diagnosis usually results when these aneurysms are recognized as incidental findings during imaging for other diseases. Rupture reportedly occurs in 13% of these aneurysms, is usually intraperitoneal, and carries a mortality of 50%.91 Aneurysmal rupture rarely occurs into the gastrointestinal tract. Intervention is warranted for all symptomatic celiac artery aneurysms and those exceeding 2 cm in size.

Endovascular treatment of celiac artery aneurysms is infrequently performed because of the need to occlude the hepatic, splenic, left gastric arteries, and in some cases the inferior phrenic arteries. Nevertheless, successful endovascular therapy of these aneurysms has been reported and has a role, especially in patients at high risk for open surgery.2,15,93,94

Open surgical procedures are the most common intervention for celiac artery aneurysms, and are recommended unless prohibitive operative risks exist. Most nonruptured aneurysms can be treated through an abdominal approach, although in the presence of acute expansion or rupture, a thoracoabdominal incision may be favored. Arterial reconstruction of the celiac trunk is preferred following aneurysmectomy,91,95 although simple aneurysmal exclusion with ligation of entering and exiting branches may be performed in select patients.11,91,96,97 If the latter is undertaken, the foregut collateral blood flow to the liver must be sufficient to prevent severe hepatic ischemia. When such is not the case, an aortoceliac or aortohepatic artery bypass is usually undertaken. Successful outcomes of open surgical therapy are greater than 90%.91

Gastric and Gastroepiploic Artery Aneurysms

Gastric and gastroepiploic artery aneurysms account for 4% of splanchnic artery aneurysms (Figure 43-9). Gastric artery aneurysms are tenfold more common than gastroepiploic artery aneurysms. Men are twice as likely than women to have these aneurysms. The majority of these lesions affect patients older than 50 years. Most of these aneurysms are solitary and are acquired as a result of either periarterial inflammation or medial degeneration. Arteriosclerosis, when present, is invariably a secondary accompaniment of these lesions. Gastric and gastroepiploic artery aneurysms are usually very small, and a search for them is often tedious if they have not been localized preoperatively by detailed imaging.

FIGURE 43-9 Gastroepiploic artery aneurysm. Selective celiac arteriogram documenting small saccular aneurysm.

(From Zelenock GB, Stanley JC: Splanchnic artery aneurysms. In Rutherford RB, editor: Vascular surgery, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2000, WB Saunders, p 1378.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree