INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Nonoperative observation is appropriate for the child with minimal or no symptoms and an airway that is judged to be adequate to support the child. Prolonged follow-up is necessary as many children develop symptoms with exercise. Most stenotic tracheas grow in proportion to the child’s growth. Occasional patients with congenital tracheal stenosis may not present until later when either exercise or endotracheal intubation uncovers the stenotic trachea. Repair in older children is easier than in neonates so deferral of operation is often wise if the tracheal obstruction is not severe. Infants are often first diagnosed in the midst of a viral syndrome and their respiratory symptoms improve dramatically after resolution of their acute illness. Children like this can usually be observed. Alternatively infants who present with “dying spells” require repair.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

A plain chest radiograph is always the starting point of evaluation. Careful examination of the tracheal air column can often give an estimate of tracheal pathology. A barium swallow is useful in infants with malacia and esophageal atresia after repair to exclude recurrent tracheoesophageal fistula. It is also useful to diagnose vascular rings although computed tomography (CT) is now more commonly used and is more definitive. Cross-sectional imaging (CT or magnetic resonance) is very important in evaluating congenital tracheal stenosis (to detect associated anomalies such as a pulmonary artery sling) and extrinsic compression (to detect vascular or cardiac causes of extrinsic compression). CT is more useful in small children as the image time is very short requiring only very short sedation periods. Axial, coronal, and sagittal views, along with 3D reconstruction of the airway allow accurate diagnosis of almost all tracheal lesions. Associated cardiac anomalies should be sought in congenital tracheal stenosis with echocardiography, especially cardiac anomalies that may require concomitant repair (left pulmonary artery sling, ASD, VSD). A pediatric otolaryngologist should examine the larynx in cases of congenital tracheal stenosis to search for other congenital obstructive lesions of the upper airway. If severe pathology is found usually the laryngeal problems are corrected before the tracheal pathology.

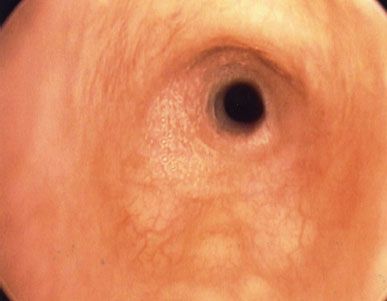

Figure 39.1 Bronchoscopic view from just below the vocal cords of a child with congenital O-ring long-segment tracheal stenosis. Notice the circular tracheal rings.

Bronchoscopic evaluation of the airway is the most critical component in evaluation (Fig. 39.1). The extent of the lesion must be evaluated and measured, the quality and extent of normal trachea must be ascertained, and the character of the tracheal mucosa assessed. Malacia is best evaluated during spontaneous breathing, requiring close cooperation with the anesthesiologist.

Infants and small children are evaluated with a very small (infant size) ventilating rigid bronchoscope (Karl Storz, Culver City, CA) with ultrathin 0-degree telescopes. Older children are evaluated with small-sized (4, 5, and 6) ventilating rigid bronchoscopes with the aid of a magnifying 0-degree telescope. Ultrathin flexible bronchoscopes with an outside diameter of only 3 mm are useful for examining infants’ airways and larger standard pediatric flexible bronchoscopes are used for older children. The operating surgeon is the optimal person to assess the airway preoperatively to decide if operation is indicated and to plan the repair. Intraoperative bronchoscopy (by pulling back the endotracheal tube over a flexible bronchoscope) is frequently helpful to decide where to make a tracheal incision and also to examine the completed repair.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Positioning

Patients are operated on in the supine position. Neonates and infants who undergo repair are best done on either cardiopulmonary bypass or ECMO. ECMO has the advantage of allowing transitioning back to the NICU or PICU fully supported without the need for high airway pressures. A small bump under the shoulders is used to extend the head and neck. The head is supported by a gel doughnut. Antibiotics are administered.

Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree