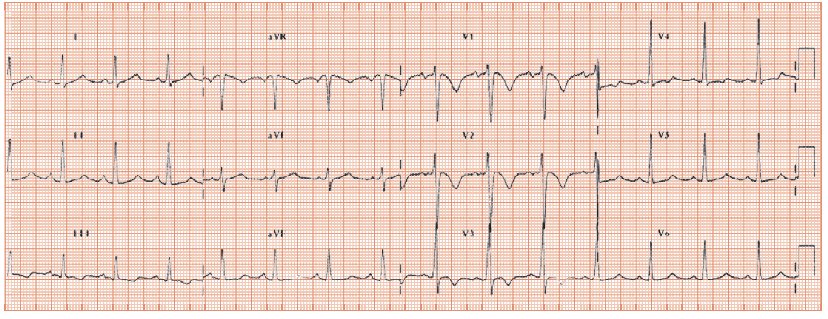

Fig. 25.2 Myocarditis. Sinus tachycardia, heart rate 91 b/min, non-specifically abnormal P wave, normal PR interval, good voltage QRS complexes throughout. T wave inversion, deep, in leads V1–3; ST depression V4–6. This ECG could have many causes, including ischaemic heart disease, pulmonary emboli (sinus tachycardia, and right heart strain appearance in leads V1–3). However, this patient had a severe myocarditis.

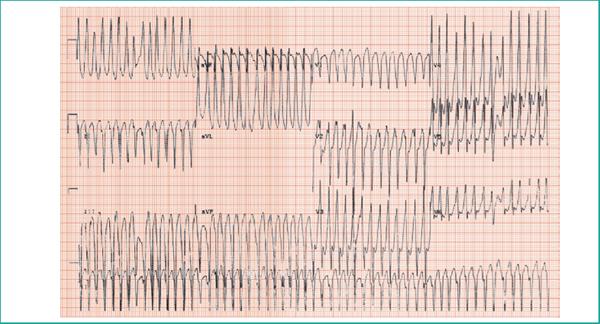

Fig. 25.3 Not an easy ECG. Gross tachycardia, heart rate ±180 b/min, irregular, suggesting atrial fibrillation. Broad QRS of 200 ms. Slurred upstroke in leads V5/6, left axis deviation, apparent Q waves in the inferior leads. This is Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, with ‘pre-excited’ atrial fibrillation. The heart rhythm and low blood pressure responded to DC cardioversion.

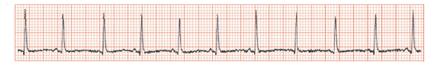

Fig. 25.4 Rhythm strip showing varying height of the R wave, termed QRS alternans, due to a large pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade.

Shock is ‘low blood pressure with evidence of organ malperfusion’; recognized by cold skin, confusion and low urine output. It is common and has a high mortality. The causes include:

- Primary cardiac causes, with a low cardiac output. The patient is cool, with high left atrial pressures (pulmonary oedema and breathlessness) and right-sided pressures (increased jugular venous pressure; peripheral oedema). Causes include valve disease (acute, e.g. rupture of aortic or mitral valve due to endocarditis, or chronic, e.g. decompensated aortic stenosis, myocardial infarction [MI], pericardial effusion with tamponade, and pulmonary emboli).

- Sepsis, especially gram-negative septicaemia.

- Hypovolaemia, especially from gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Miscellaneous causes including Addisonian crisis and spinal trauma.

Management

The key principle is to rapidly establish the cause and institute treatment. For diagnosis, in addition to the history and physical examination, investigations help particularly the ECG, cardiac ultrasound and blood tests.

The ECG in shock

- Normal: a cardiac cause is unlikely.

- Sinus tachycardia, a common non-specific finding. Patients with septic shak often feel warm, whereas in cardiogenic shock they often have cool skin. Occasionally shock relates to myocarditis (Fig. 25.2), where the diagnostic clue is a tachycardia out of proportion to the haemodynamic disturbance. The ECG usually shows other changes, including ST flattening/depression, T wave inversion, conducting tissue disease or, much more rarely, ST elevation.

- Arrhythmias commonly complicate but infrequently cause shock (unless other factors are present):

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree