Segmentectomy and Lesser Pulmonary Resections

Joseph LoCicero III

Parenchyma-sparing pulmonary resections are important procedures for many patients. Although lobectomy and pneumonectomy remain standard operations for patients with primary lung cancer who can tolerate that sort of resection, many authors advocate less than lobectomy as an alternative operation, particularly in patients with limited pulmonary reserve. In cases where resection of pulmonary metastases may provide prolonged survival, a lesser parenchymal resection is an ideal procedure. These techniques are used for the diagnosis of the indeterminate pulmonary nodule.

Segmentectomy

Segmentectomy, a form of resection popularized in the mid-1900s, is an anatomic operation because it removes the segmental bronchus back to its primary branch, along with all of the lung parenchyma and lymph node groupings drained by the bronchus and its associated segmental pulmonary artery. This technique was first used for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, and other suppurative pulmonary lesions. After effective antituberculous chemotherapy and broad-spectrum antibiotics for suppurative diseases were developed, the operation became less common in the United States. However, it remained a mainstay of the surgeon’s armamentarium not only in other countries throughout parts of Europe and Asia but also in countries as near as Mexico and South America.

Since its revival by Jensik and associates in 197310 and its use in early lung cancer as suggested by Shields and Higgins in 1974,24 authors’ reports have appeared in every decade.5,11,23 Studies by Read and coworkers26 and Warren and Faber31 showed that excellent results can be achieved in patients with early (T1N0) cancers. For those with primary lung cancer and poor pulmonary function, Kodama12 and Cerfolio3 and their associates note that segmentectomy can lead to long-term survival.

The only randomized trial on this subject comes from the Lung Cancer Study Group and was reported in 1995 by Ginsberg and Rubenstein.7 However, the report combines both segmentectomy and wedge resection. Together, they have a worse outcome (greater than twofold local recurrence) as compared with lobectomy.

Since then, several groups are readdressing this issue. Most significant is the study by Okada and colleagues,18 who performed a multi-institutional study beginning in 1992 and reported in 2006 on what they termed “radical segmentectomies” in patients with primary lung cancers <2 cm. They began with a segmentectomy and extended the margins with wedge resections if the intrapulmonary nodes were positive. In their study, patients were enrolled preoperatively. The results of the radical segmental resection group (n = 305) were compared with those of the lobar resection group (n = 262). Although patients were matched and all could tolerate lobectomy, they were not randomized. The 5-year disease-free and overall survivals were 85.9% and 89.6% for the radical segmental resection group and 83.4% and 89.1% for the lobar resection group, respectively. In 2008, Sienel and colleagues25 reported on a nonrandomized series of patients with high-risk conditions and stage I lung cancer; 35 patients had segmentectomy and 25 had wedge resections of their tumors. The authors noted a 5-year survival rate of 63%, but there was local recurrence in 40% of the patients with wedge resections compared with only 11% in the segmentectomy group (p <0.007). Cancer-related deaths were 52% in the wedge resection patients compared with only 20% in the segmentectomy group (p<0.005).

With the resurgence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in urban areas and the development of drug-resistant atypical strains, this technique remains vitally important to the eradication of suppurative disease while maximally preserving a normally functioning lung. Takeda and colleagues27 used segmentectomy alone or in combination for pulmonary tuberculosis in 17% of cases. Agasthian1 and Ashour2 and their associates reported control of bronchiectasis by segmentectomy alone in 13% to 16% of patients. Segmentectomy has been used in patients with severe Aspergillus and pulmonary mycotic infections. Massard15 and Temeck28 and their colleagues noted that segmentectomy has significant complications in these patients but that these are not different from complications associated with other types of infections.

Even congenital lesions can be managed with segmental resections. Nuchtern and Harberg17 used segmentectomy for intralobar lung cysts. Sapin and associates22 were able to use segmentectomy in one-third of the patients they treated for congenital adenomatoid disease of the lung.

Technique

The most popular approach at present is the standard lateral thoracotomy position using general anesthesia with the ability to provide single-lung ventilation. Alternatively, an axillary approach may be used to limit the incision. A thoracoscopic approach is possible as well.

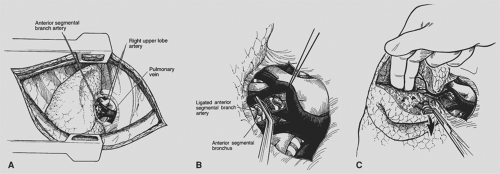

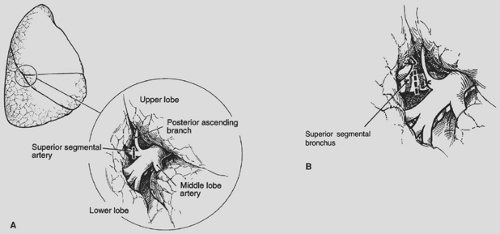

Initial steps in segmentectomy are the same as for any standard resection of the lung. The surgeon must be familiar with the intraparenchymal anatomy of the bronchus and pulmonary artery to accomplish a segmentectomy successfully. The hilar structures are identified and the major fissure is opened. On the right side of the chest, the bronchus is the most posterior hilar structure. As one proceeds into the hilum, the upper lobe branches of the pulmonary artery are the most superior hilar structures (Fig. 32-1). In the major fissure, the pulmonary artery can be exposed, demonstrating the continuation of the main pulmonary artery into the lower lobe. Anterior and posterior branches originate opposite one another and go, respectively, to the middle lobe and the superior segment of the lower lobe, forming a cross. Often, a posterior ascending branch arises from the posterior segmental artery and supplies part of the posterior segment of the upper lobe (Fig. 32-2).

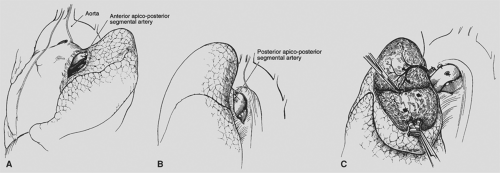

On the left side of the chest, the pulmonary artery crosses superiorly above the left mainstem bronchus to become the most posterior structure in the hilum. The apicoposterior and anterior and segmental branches are located anteriorly and superiorly. A separate posterior segmental branch is often found posteriorly on the main pulmonary artery, just at or above the major fissure (Fig. 32-3). In the major fissure, the lingular branches anteriorly and the superior segment branch posteriorly form a cross on the continuation of the pulmonary artery (Fig. 32-4). The surgeon must be mindful of the high degree of variability of the branches of the pulmonary artery and carefully identify each branch before ligation (see Chapter 5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree