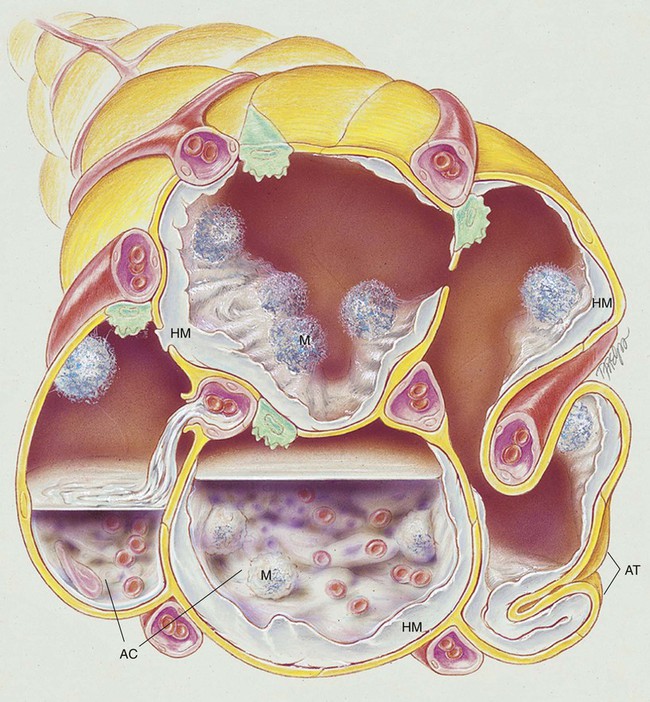

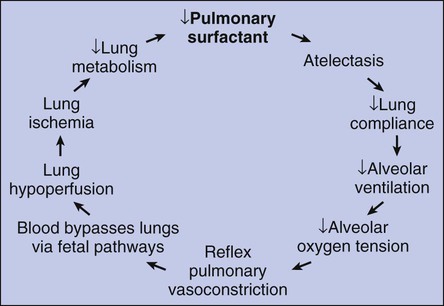

After reading this chapter, you will be able to: • List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with respiratory distress syndrome. • Describe the causes of respiratory distress syndrome. • List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with respiratory distress syndrome. • Describe the general management of respiratory distress syndrome. • Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAP presented in the case study. • Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve. Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) is the most common cause of respiratory failure in the preterm infant. Over the past several decades, a number of names have been used to identify infants with RDS (Box 34-1). A common thread running through most of the names is the term “respiratory distress,” which characterizes an immature lung disorder in a preterm infant caused by inadequate pulmonary surfactant. RDS is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the premature infant born after less than 37 weeks’ gestation. The introduction of exogenous surfactant therapy has greatly improved the clinical course of this disorder and reduced the morbidity and mortality rates. In what appears to be an effort to offset alveolar collapse, the respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and some alveoli dilate. As the disease intensifies, the alveolar walls become lined with a dense, rippled hyaline membrane identical to the hyaline membrane that develops in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) of the adult patient (see Chapter 27). The membrane contains fibrin and cellular debris. During the later stages of the disease, leukocytes are present, and the hyaline membrane is often fragmented and partially ingested by macrophages. Type II cells begin to proliferate, and secretions begin to accumulate in the tracheobronchial tree. The anatomic alterations in RDS produce a restrictive type of lung disorder (see Figure 34-1). The major pathologic or structural changes associated with RDS are as follows: • Interstitial and alveolar edema and hemorrhage • Intraalveolar hyaline membrane • Pulmonary surfactant deficiency or qualitative abnormality • Hypoxia-induced vasospasm and vasoconstriction: • Hyperperfusion (in cases lasting longer than 24 hours; leads to excessive lung fluid and pulmonary edema) 1. Because of the pulmonary surfactant abnormality, alveolar compliance decreases, resulting in alveolar collapse. 2. The pulmonary atelectasis causes the infant’s work of breathing to increase. 3. Alveolar ventilation decreases in response to the decreased lung compliance and infant fatigue, causing the alveolar oxygen tension (Pao2) to decrease. 4. The decreased Pao2 (alveolar hypoxia) stimulates a reflex pulmonary vasoconstriction. 5. Because of the pulmonary vasoconstriction, blood bypasses the infant’s lungs through fetal pathways—the patent ductus and the foramen ovale. 6. The lung hypoperfusion in turn causes lung ischemia and decreased lung metabolism. 7. Because of the decreased lung metabolism, the production of pulmonary surfactant is reduced even further, and a vicious cycle develops (Figure 34-2).

Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

Etiology and Epidemiology

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine