Resection of Posterior Mediastinal Lesions

Joseph B. Shrager

The posterior mediastinum is bounded anteriorly by the posterior pericardium and extends posteriorly to the chest wall and laterally to include the costovertebral sulci. It contains the descending thoracic aorta, inferior vena cava and azygous veins, the sympathetic chains, and origins of the intercostal nerves at their nerve roots, and it is generally defined to include the esophagus and associated vagi as well. Most anatomic systems consider only lesions that are caudal to the fourth thoracic vertebral body to be within the posterior mediastinum, with more cephalad lesions resting within the superior mediastinum.

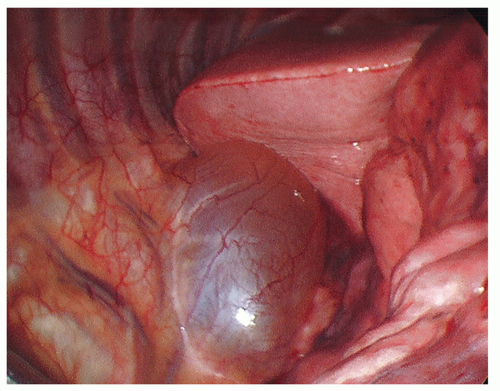

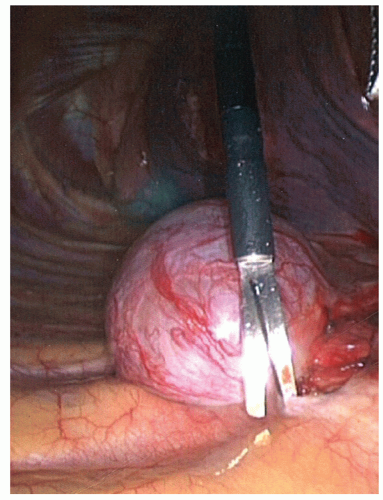

The majority of posterior mediastinal masses occurring in adults are benign. These lesions can be usefully classified according to whether they are cystic or solid on radiographic evaluation. Cystic masses in this region typically represent bronchogenic cysts (Fig. 15.1) or esophageal duplication cysts, whereas solid masses are most commonly benign neurogenic tumors (Figs. 15.2 and 15.3; e.g., schwannomas, neurofibromas, or ganglioneuromas). These neural tumors usually arise from the sympathetic chain or the proximal intercostal nerves, but sometimes the exact anatomical origin does not even become clear intraoperatively. Occasionally, one comes across a patient with a pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma, which arise from the randomly located mediastinal paraganglionic cells and may secrete hormones. At initial office evaluation, one should be alert to the presence of hypertension or palpitations that should dictate measurement of urine metanephrines. Esophageal leiomyomas (benign intramuscular tumors within the esophageal wall) are also generally grouped among the posterior mediastinal lesions. The approach to these lesions and to esophageal duplication cysts differs somewhat from the approach to lesions that are unassociated with the esophagus.

In many cases, posterior mediastinal masses come to light as asymptomatic radiographic abnormalities. They may uncommonly, however, present with signs of infection (in the case of infected cysts), or with dysphagia, chest pain, respiratory complaints, or neurological changes (e.g., Horner’s syndrome from tumors involving the upper sympathetic trunk; lower extremity symptoms from dumbbell tumors) resulting from mass effect on adjacent structures. Esophageal lesions can, of course, cause dysphagia but they too are often asymptomatic.

At present, because of the growing availability of less morbid, minimally invasive approaches to posterior mediastinal masses, most authors recommend resection even when lesions are asymptomatic. I believe that the recommendation about whether to proceed with resection of a posterior mediastinal mass needs to be individualized. Clearly, a symptomatic lesion is best managed by resection, except in unusual circumstances. When an asymptomatic lesion has all of the radiographic characteristics of a benign cyst or tumor (i.e., smooth margins, simpleappearing cyst material, minimally positron emission tomography PET) positive if PET has been done), then the age and general medical condition of the patient should be the key considerations. Since these lesions do generally grow—albeit at a fairly slow rate—it is likely that a young patient will eventually develop symptoms due to impingement on surrounding structures or infection of a cyst. Patients under the age of 60, then, who are otherwise good surgical candidates, are best managed by resection. For older patients, or those who have substantial comorbidities, it is perfectly reasonable to follow these benignappearing, asymptomatic lesions with radiographic studies and operate only if they begin to grow dramatically, the patient develops symptoms, or a change in radiographic appearance suggests malignancy. In any case, there is no urgency to remove these cysts and tumors. The significance of the very few reports of development of malignancy within a benign posterior mediastinal mass is likely overstated.

SURGICAL PRINCIPLES

Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery vs Thoracotomy

Resection of posterior mediastinal masses may be accomplished by means of either video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) or thoracotomy. The procedure, apart from the incisions, is essentially the same with either approach, and the goal is complete resection. With some exceptions, VATS is considered preferable to thoracotomy in this setting. It has been well established that VATS results in less postoperative pain and quicker functional recovery. Some surgeons argue that a VATS approach may be more likely to leave a patient with microscopic residual disease. In our experience and that of others, however, recurrences of these lesions are very rare after VATS excision. Given the low recurrence rate and the fact that these masses are almost always benign, we believe that the risk-benefit ratio favors VATS in most cases.

There are, however, several circumstances in which thoracotomy is indicated from the outset. A suggestion of malignancy (in particular, frank invasion of surrounding structures) on preoperative imaging mandates exploration and resection by thoracotomy; in this situation, the potential consequences of positive margins justify the more aggressive approach. The presence of active infection within a cyst is a relative indication for thoracotomy, in that it can cause disruption of normal tissue planes and thereby render VATS dissection more difficult and possibly hazardous. Masses larger than approximately 6 cm also call for an open approach in my opinion: such lesions are typically more difficult to mobilize safely from surrounding structures than smaller lesions, they are more likely to be malignant (though this is still rare), and their removal between the ribs is likely to necessitate substantial rib spreading, which may negate the benefit of true VATS. Another approach is to attempt

VATS for these larger lesions, but to have a low threshold to convert to thoracotomy if difficulty is encountered. If the dissection can be completed by VATS, one can then typically remove larger tumors by resecting a small portion of the rib without sacrificing an intercostal nerve. It is likely that this will result in less pain and earlier recovery than a standard thoracotomy with rib spreading, but this has to my knowledge never been studied.

VATS for these larger lesions, but to have a low threshold to convert to thoracotomy if difficulty is encountered. If the dissection can be completed by VATS, one can then typically remove larger tumors by resecting a small portion of the rib without sacrificing an intercostal nerve. It is likely that this will result in less pain and earlier recovery than a standard thoracotomy with rib spreading, but this has to my knowledge never been studied.

Other Preoperative Issues

Any patient with a centrally located cyst should undergo bronchoscopy to rule out the rare occurrence of a communication with the bronchial tree. This may be suggested on computed tomography (CT) scans by the presence of an air-fluid level. If a communication is identified, strong consideration should be made to proceed with thoracotomy rather than VATS. When a cyst arises from or abuts the esophagus, the possibility of a communication between the cyst and the esophageal lumen should be similarly investigated. To rule out this phenomenon, I obtain barium esophagography during the preoperative workup, followed by esophagoscopy in the operating room prior to the start of the operation. If a communication is identified, thoracotomy is performed. After excision of an esophageal duplication cyst with a communication, reapproximation of the esophageal mucosa is a paramount consideration; in my view, this is still most reliably carried out through an open approach.

Fig. 15.3. Computed tomographic image of a typical benign neurogenic tumor in the costovertebral sulcus. |

In cases of suspected leiomyoma of the esophagus, preoperative investigation with esophagoscopy should be done to confirm the presence of intact overlying mucosa, which is virtually pathognomonic of this disease. If the mucosa is intact, the possibility of malignancy is essentially ruled out. Simultaneously, endoscopic ultrasonography may be performed to establish the depth to which the esophageal wall is involved. With a preoperative diagnosis of probable leiomyoma, VATS is the approach of choice in our practice.

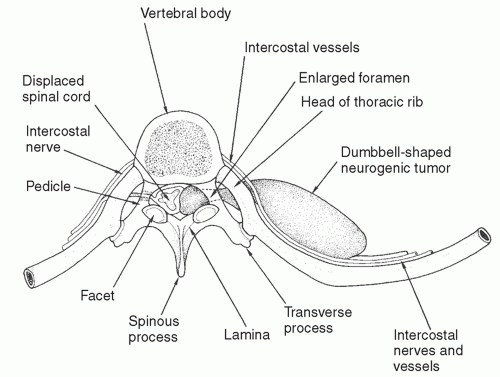

The so-called dumbbell neurogenic tumors (tumors that invade the neural foramen and have a spinal canal component) are special cases (Fig. 15.4). Any solid mass in the costovertebral sulcus that cannot be clearly separated on CT imaging from the neural foramen should be evaluated by means of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Although invasion of the neural foramen by tumor is not in itself an indication for thoracotomy, it does necessitate a combined approach with neurosurgical involvement for the intraspinal portion of the procedure. Several versions of such an approach have been described, including a posterior approach via costotransversectomy or extension of a midline incision into a posterolateral thoracotomy, through which both the intraspinal and intrathoracic components of the tumor

can be resected. We prefer to perform the following approach: under a single anesthetic, the neurosurgeons first resect the intraspinal component (laminectomy and intervertebral foraminotomy), then the patient is repositioned to lateral decubitus and we carry out the remainder of the procedure (generally via VATS). Failure to diagnose a dumbbell tumor preoperatively and plan an appropriate combined operation may lead to inadvertently cutting through tumor from within the chest. This can result in tumor hemorrhage within the spinal canal and spinal cord compression with disastrous consequences.

can be resected. We prefer to perform the following approach: under a single anesthetic, the neurosurgeons first resect the intraspinal component (laminectomy and intervertebral foraminotomy), then the patient is repositioned to lateral decubitus and we carry out the remainder of the procedure (generally via VATS). Failure to diagnose a dumbbell tumor preoperatively and plan an appropriate combined operation may lead to inadvertently cutting through tumor from within the chest. This can result in tumor hemorrhage within the spinal canal and spinal cord compression with disastrous consequences.

Fig. 15.4. A neurogenic dumbbell tumor showing compression of the spinal cord, enlarged intervertebral foramen, and a large posterior mediastinal tumor component. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree