Replacement of the Esophagus with Jejunum

Henning A. Gaissert

Cameron D. Wright

Douglas J. Mathisen

Replacement of the esophagus remains a challenge for esophageal surgeons and their patients. The ideal conduit should restore normal swallowing, maintain active peristalsis, protect from acid reflux, be of sufficient length to replace as much of the esophagus as necessary, have a reliable arterial and venous supply, and not interfere with the function of the rest of the alimentary tract. No substitute satisfies all these criteria. None allows for normal swallowing. These principal observations are reason enough to preserve the esophagus whenever possible, particularly in benign disease.

Each of the available conduits, stomach, colon, or jejunum, has certain features that make it suitable for esophageal replacement. Certain circumstances may dictate the use of one conduit and exclude others. The surgeon treating esophageal disease must be familiar with all options. Successful replacement requires in-depth understanding of the technical aspects of each individual procedure. Proper patient selection and strict attention to preoperative and postoperative care ensures the greatest chance for a successful outcome and near-normal swallowing.

Background

Techniques for intestinal interposition of the esophagus were developed at the beginning of the twentieth century. Jejunum was first used as an antethoracic swallowing conduit in 1906 by Roux,25 who performed a staged bypass of a caustic esophageal stricture with connection to the cervical esophagus 4 years later. Herzen15 of Moscow successfully completed a similar two-stage procedure for a benign stricture of the esophagus in 1907. The jejunal segment was placed subcutaneously in both patients. Intrathoracic substernal and posterior mediastinal placements of the jejunum were accomplished successfully in 1942 and 1945 by Rienhoff,23 of Baltimore. The British surgeon Brain4 used a short jejunal interposition between the distal esophagus and stomach for reflux-related strictures in 1951. Several years later, Merendino and Dillard19 demonstrated in animal experiments that an interposed jejunal segment prevented gastroesophageal reflux and peptic esophagitis after excision of the lower esophageal sphincter. Merendino and Thomas20 reported the first large series of jejunal interposition of the distal esophagus, which included 33 patients. Benign strictures and cardiospasm were the most common indications (82%). A single-stage procedure was used in all but two patients. Operative mortality was 12%. All patients had relief of dysphagia.

Indications

In adults, jejunal interposition is best suited for replacement of the distal esophagus. The indications for short-segment interposition of either jejunum or colon at Massachusetts General Hospital are listed in Table 142-1. Additional length may be obtained to reach the level of the aortic arch. Anastomosis to the lower cervical esophagus can rarely be achieved in adult patients. Therefore indications for jejunal interposition of the esophagus are largely confined to disorders of the lower esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Exceptions to this rule are its use in children, reported by Ring and associates,24 and when jejunal blood supply is supported by anastomosis to internal thoracic or cervical vessels, as recorded by Heitmiller and colleagues.14 The last approach increases the complexity and, in any but the most experienced hands, the risk of complications by adding two microvascular anastomoses.

Complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease constitute the most frequent indication for resection and intestinal interposition of the distal esophagus. Nondilatable strictures and severe, refractory esophagitis after failed antireflux procedures are the most common situations encountered. The esophageal destruction is in this case limited to one esophageal segment. If continuity is restored with esophagogastrostomy after esophagectomy for complications of reflux disease, the incidence of severe recurrent reflux, esophagitis, anastomotic stricture, and late hemorrhage is high. An intrathoracic gastric anastomosis is therefore less desirable than either colon or jejunum.

Failed therapy or complications of motility disorders represent other important indications for intestinal interposition of the distal esophagus. Failed Heller myotomy for achalasia may lead to severe reflux and stricture not amenable to dilation and antireflux surgery. Colon and jejunum interposition was favored by Belsey3 and by Jamieson16 and Picchio21 and their associates to reduce postoperative gastroesophageal reflux. Sigmoid esophagus secondary to advanced achalasia with or without mucosal stricture may require resection. While total esophagectomy

is preferred by most, a short jejunal interposition improves esophageal drainage if longer conduits are unavailable.

is preferred by most, a short jejunal interposition improves esophageal drainage if longer conduits are unavailable.

Table 142-1 Indications for Short-Segment Interposition at Massachusetts General Hospital | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Scleroderma often results in severe gastroesophageal reflux and stricture formation. Antireflux surgery is less likely to succeed in such instances. When it fails or nondilatable strictures result, resection of the distal esophagus and colon or jejunal interposition is indicated, as suggested by Brain4 and Mansour and Malone.18

Caustic strictures tend to involve the entire length of the esophagus and are rarely isolated to the distal esophagus. For this reason, jejunum is used infrequently, but it may be suitable in children.

Nonvariceal acute hemorrhage of the esophagus is usually controlled by nonsurgical methods. In those rare cases of uncontrollable hemorrhage from an ulcer, esophagitis, or Barrett’s mucosa, resection may be the only option available for control. Because most cases are related to complications of reflux and occur in the setting of unprepared colon, jejunal interposition is probably the preferable way to reconstruct the esophagus. Its use avoids the potential for severe complications from gastro- esophageal reflux after esophagogastrectomy. A jejunal segment can be constructed safely without bowel preparation, is resistant to acid reflux, and can be an effective antireflux operation.

After resection for carcinoma, the preferential use of jejunum was reported in two circumstances. Stein and colleagues26 reconstructed the defect after distal esophagectomy for early adenocarcinoma with a short segment, arguing that early tumors require neither radical resection nor extensive lymphadenectomy. The authors believe that limited resection and the avoidance of esophagogastrostomy will preserve a higher quality of life. In the other circumstance, reconstruction after radical esophagectomy with cervical anastomosis was accomplished by Ascioti and coauthors1 using jejunum “supercharged” with an anastomosis to the internal mammary vessels. Of 26 patients so treated (including 3 in whom both stomach and colon were available), 24 were discharged with an intact jejunal segment. Two patients lost their graft; there was no mortality. Six months after reconstruction, 95% of patients (20 of the original 26 patients) tolerated a regular diet, although 23% (5 of 21 patients) depended on either partial or full tube feeds. While the operation may avoid reflux and the risk of recurrent Barrett’s mucosa seen after conventional esophagogastrostomy, this concept has not been substantiated by a sufficient number of observations.

Esophageal perforation would be an unusual indication for jejunal interposition. Most perforations are associated with gross contamination of the pleural cavity and therefore are not suitable for an anastomosis in such a contaminated field. The condition of the patient often does not allow the extra time necessary for a procedure as complex as jejunal interposition. The primary goal in this situation is to deal with the perforation and save the patient’s life. The only circumstance in which jejunal interposition may be appropriate is that of the patient with iatrogenic perforation of a nondilatable stricture diagnosed immediately after injury who is in good condition with minimal contamination and an irreparable stricture.

Contraindications to jejunal interposition include short bowel syndrome and Crohn’s disease, while a short, fat jejunal mesentery limits cephalad reach. Anatomic variations may exist that would preclude the use of jejunum as well.

Vascular Supply of the Jejunum

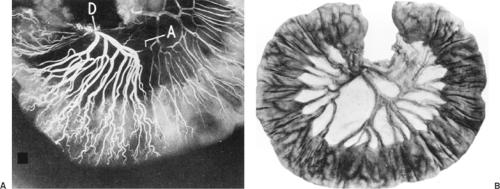

Despite the virtual absence of atherosclerotic disease, the jejunal vascular pedicle is less reliable than other conduits for two reasons, one anatomic and the other technical. In a study of anatomic variations in jejunal arterial arcades, Barlow2 found common abnormalities affecting collateral blood supply in 25% of specimens. Significant variations consisted of narrow vessels between adjacent jejunal arteries in 16%, and complete interruption between jejunal arcades in 6% of specimens (Fig. 142-1). Despite the frequency of this observation, however, clinical ischemic complications are rare, probably because arterial ischemia is recognized most often during preparation of the segment. The technical aspect of unreliability refers to the extent of dissection necessary to straighten the intestinal tube on its radially organized vascular supply. Stripping the peritoneal cover of mesenteric vessels—veins in particular—risks injury and kinking of these vessels. Obstructed venous drainage is deleterious for graft survival and may, when not discovered during operation, lead to delayed graft necrosis. Meticulous attention to a straight course of the vascular pedicle avoids this pitfall.

Preoperative Preparation

Little preoperative preparation is required for jejunal interposition. In most patients, a suitable backup must be available if the use of jejunum is precluded. The usual alternative is colon; therefore all patients should have a bowel preparation. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are given perioperatively.

Operative Technique

Posterior Mediastinal Position

Single-lung ventilation through a double-lumen tube provides the best exposure for the operation. Esophagogastroscopy is

performed to assess the pathology and its extent. For short-segment replacement of the lower esophagus, the patient is placed in the left thoracotomy position, rotating the left hip backward for abdominal exposure. A left thoracoabdominal incision through the sixth or seventh intercostal space with peripheral diaphragmatic incision provides excellent exposure. The entire length of abnormal esophagus is mobilized. This step includes circumferential dissection of the gastroesophageal junction, which, after prior surgical procedures, may be involved in dense scarring.

performed to assess the pathology and its extent. For short-segment replacement of the lower esophagus, the patient is placed in the left thoracotomy position, rotating the left hip backward for abdominal exposure. A left thoracoabdominal incision through the sixth or seventh intercostal space with peripheral diaphragmatic incision provides excellent exposure. The entire length of abnormal esophagus is mobilized. This step includes circumferential dissection of the gastroesophageal junction, which, after prior surgical procedures, may be involved in dense scarring.

Figure 142-1. A: Angiogram of proximal mesenteric arcade. Injection of the duodenal end of the arcade (D) demonstrates narrowing in the arcade (A). B: Photograph of proximal jejunum with interrupted arcade and absence of communication between two adjacent branches of the superior mesenteric artery. (From Barlow TE. Variations in the blood supply of the upper jejunum. Br J Surg 1955;43:473. With permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|